Schools of Rock

From Guitar Hero to online classes and from apps to in-person jam sessions, musicians plug into curricula that get them amped up

Growing up in a musical family, Matrisha Armitage felt pressured to follow a traditional path in music education. The judgment of others led her to view music as a chore instead of her passion. Just the same, she and the young man who later became her husband started a high school band—something meant to be fun.

Armitage wanted to create music freely and help others do the same. Nearly a decade later, she formed the nonprofit Music Education & Performing Arts Association, which uses group-led jam sessions to support people of all ages and abilities in performing music and arts in safe spaces, free of expectations.

“How we’re teaching seems to work for everyone,” Armitage said. “Teaching is really just being super supportive of helping students know how to find these resources on their own. I think every music education moment needs to be structured for that student.”

Music education is not one size fits all. With technological advances, the way musicians are teaching and learning the craft is dramatically changing musicians’ skills. From video games to online classes and from self-taught apps to traditional music schools, students tune in whatever way feels comfortable to find their groove.

Tech hero

In 2005, the music rhythm video game Guitar Hero revolutionized the way songs were purchased and downloaded during the iTunes era. Guitar Hero and Rock Band posted combined sales of over $105 billion in 2007—more than all of the digital sales for iTunes and ILK. Aside from the game persuading the biggest band in history—The Beatles—to go digital, Guitar Hero influenced younger players to pursue real instruments.

Although Guitar Hero wasn’t necessarily a music education platform, its success shed light on the role technology plays in the evolution of consuming, teaching and learning music.

Today, iTunes no longer dominates the digital music market—new apps bring simple music lessons to our fingertips, phones and tablets carry online sessions, YouTube provides endless video tutorials, and Tik Tok offers quick music tips.

“Technology definitely changes everything,” said Shelle Soelberg, founder of the music education company Let’s Play Music. “There are more shareable resources now than ever before. It’s amazing to be able to distribute that type of work.”

When Soelberg started the company 23 years ago, she used cassette tapes. Now, Let’s Play Music has its own app delivering music directly to students.

Back to school

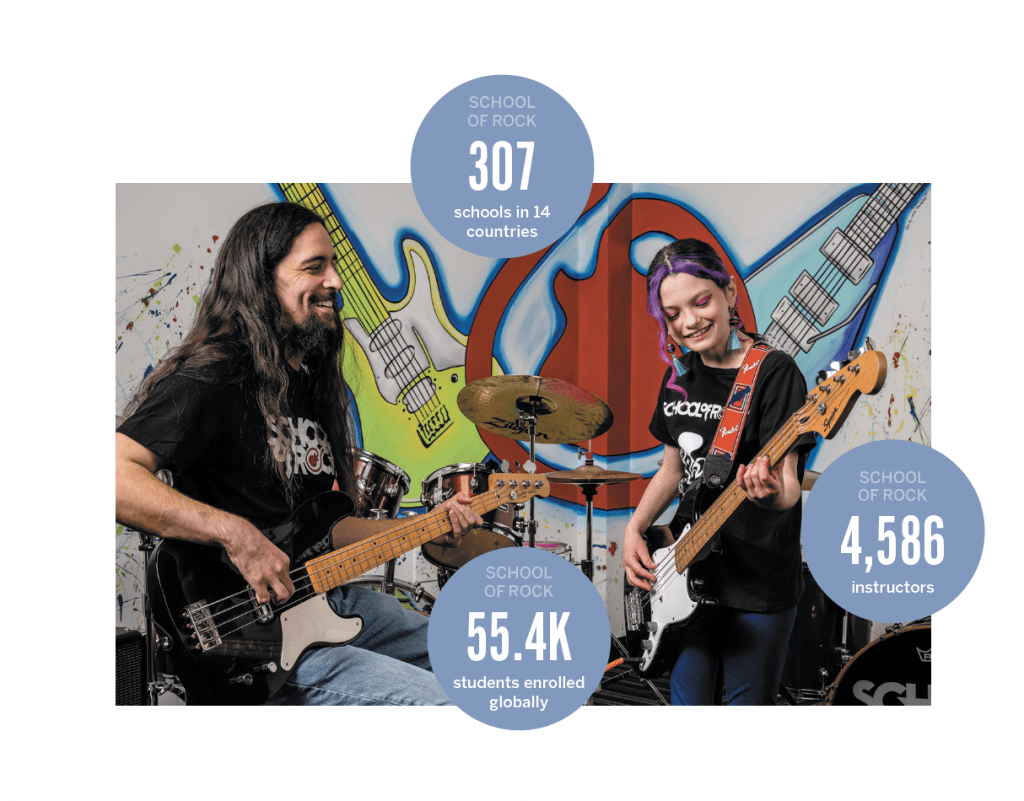

School of Rock, the global music performance company serving more than 55,000 students, also created its own app as a tool for individual at-home practice. It includes over 1,000 songs, warm-ups, feedback scores and exercises.

“It has been a game changer,” said Sam Dresser, School of Rock’s chief innovation officer. “There’s now an opportunity to not replace what we do in person, but to augment and enhance it.”

Aside from apps like GarageBand, MuseScore and Flipgrid, musicians are using programs like Coach’s Eye—a sports video analysis app—for educational purposes. Judith Bowman, professor emerita at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, said educators are using the app to replace in-person performance critiques.

“I talked to one instructor who felt it was important for her students to learn how to teach online,” Bowman said. “It was for an instrumental music methods class. So, she actually had a conversation with the athletics director at her school who was using Coach’s Eye.”

On that app, students can record video and audio, and instructors can analyze the student videos and offer feedback by drawing lines on the video and providing voiceovers.

Most importantly, social media has drastically improved artists’ reach. Emily Sangder, a graduate and now full-time employee of Berklee College of Music in Boston, said technology has created an oversaturation of content, but it also provides opportunities that weren’t there 10 to 15 years ago. With a basic understanding of production software and programs, independent musicians can now record and produce an entire album from the comfort of home.

Online sound

Music education looks different for everyone today because of the shift to remote learning spurred by COVID-19.

“It created better distinctions between those subjects that need intensive, one-on-one or small-group training, such as private lessons, versus music composition or anything else that can be taught to a larger group,” said Sebastian Huydts, interim chair for the music department at Columbia College Chicago.

Meanwhile, Bowman, who is also the author ofThe Music Professor Online, said online lessons have proven helpful but that the real magic of music is in person, in the classroom. Knowledge- or text-based courses transfer well, but it’s nearly impossible to conduct performance-based classes efficiently on the internet, she said.

“With ensembles, that really turned right upside down with the pandemic,” Bowman noted. “I don’t know how you do ensembles online.” However, online education has helped strengthen the effectiveness of in-person learning. Both ways of teaching and learning music can be effective but have different outcomes, she said.

Feel the music

For 17 years, Music To Your Home has emphasized hands-on music education. Lessons on a plethora of instruments were strictly in-person at its base in New York. The pandemic changed that, and the school now enables students from all over the globe to take lessons from the company’s 100+ educators, all professionals in the music industry.

Despite the new online reach, Vincent Reina, owner and founder of Music To Your Home, said students learn music better in interactive lessons. The idea comes from the Orff Approach created by German composer Carl Orff and colleague Gunild Keetman in the 1920s. It grew from a child’s world of play that combined music, movement, drama and speech.

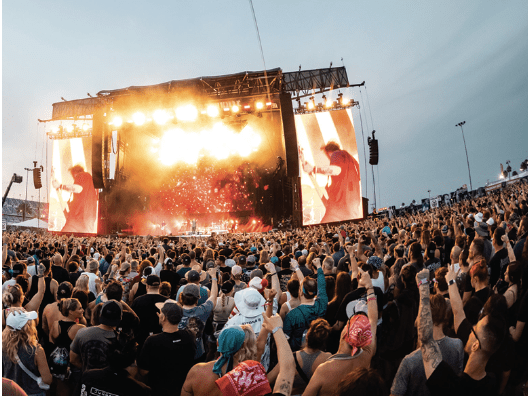

Soelberg of Let’s Play Music said the key to music education is to start lessons at an early age and focus on body movements like physically placing musical notes on a large, blank music chart. It should also incorporate the physical reaction to playing, holding or even hearing instruments live—like feeling an amplified bass pumping in your chest at a concert.

“The real thing is important,” Soelberg said. “When [someone] plays and has an interaction with an instrument, they play the tone, it goes in their ear and they get this auditory feedback and they feel the vibrations in their hands.” That teaches the ear and the mind and helps students develop skills sooner by touching the instrument and playing it themselves.

Professionals vs. academics

One of the biggest developments in the music industry over the past 20 years has been musicians’ independent approach, leaving formal music education as an option, not a necessity. There has been an influx of successful self-taught or independent artists, but technology and tools enable music education through many avenues.

Huydts, a classically trained pianist and acclaimed composer, said someone can claim to be self-taught and still learn from sources like YouTube tutorials.

“Going to school [for music] is just a shortcut to an enormous amount of information,” Huydts said. “A lifetime is not enough these days to reinvent the wheel, though.”

It’s important for an older generation of musicians, who are educated in music history and have witnessed the advent of technology to teach a younger generation of musicians to “bake their own bread, ” Huydts said.

When a musician attends a music school like Columbia College Chicago, The Juilliard School or Berklee College of Music, they’re learning directly from professionals. But students should not conform to a curriculum—the curriculum should conform to the student.

The same goes for education outside colleges. Music To Your Home’s teachers are accomplished musicians who “set the tone for a lifelong interest” in music. Not all musicians make good educators, Reina said, and they must have a bag of tricks ready at any moment.

The best part: The professionals also learn from the students.

Today vs. yesteryear

There’s no denying the role of electronics in today’s music. In Sangder’s experience at Berklee, tech makes it easier for artists to become more versatile—not only writing music but also learning to record, produce and master their sound.

So, does that mean today’s self-taught musicians have become more accomplished or skilled than those of the past?

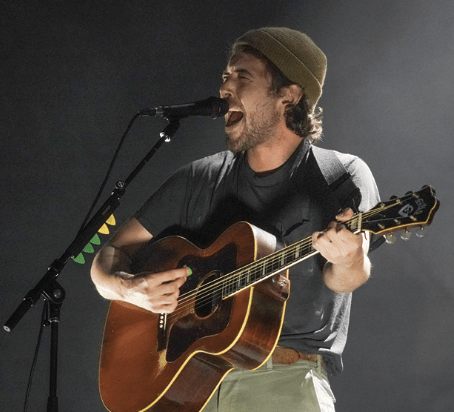

Think Jimi Hendrix. He never learned to read sheet music but picked up a guitar at a young age, playing upside down and dealing with the strings in reverse order because he was left-handed. He made himself one of the most influential guitar players in history—and he learned by doing.

Soelberg said this is where the question of “nature versus nurture”comes in. Hendrix, for example, had an immense amount of nature, meaning he was born to be a musician.

“I mean, look at Mozart, too,” Soelberg said. “He became fantastic even though he was taught in a way that’s not great.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was 4 years old when his father began teaching him music. It happened sitting at a desk, with little or no body movement and physical learning. Plus, he never attended a formal music school.

But music education has come a long way from the pen and paper approach, according to Soelberg. It’s now widely recognized that an artist needs to connect with music to learn about it.

Huydts argues it this way: “It’s a complete fallacy to think that things used to be better—it doesn’t help you create a future. You can have ideals. You can take the best of the past and try to adapt it to the needs of the future. But at a certain point, you have to realize that there’s unstoppable progress built into humanity.”

That’s not to downplay the importance of hard work. Dresser of School of Rock said access to information doesn’t directly translate into skill. It comes down to execution, which comes with time and practice.

Kendall Polidori is The Rockhound, Luckbox’s resident rock music critic. Follow her reviews on Instagram and Twitter @rockhoundlb.