Probability of Profit

To illustrate an essential trading concept for active investors, luckbox serves up POP with Netflix

One poker player bluffs his way to a jackpot with a pair of deuces, while another folds because he doesn’t have at least a straight. Their strategies diverge because the first player’s acting on instinct and the second’s playing the odds – but neither can escape the probabilities.

It’s the same in the world of options trading. Some investors spend time analyzing an entry point and then execute a trade that reflects their assumption. Others trade off of instinct or hunches. What’s interesting is that two investors can feel bullish about a stock like Netflix (Netflix) but have completely different trades and probabilities of success. That breadth of possibility seduces some into a life of trading.

So once they’re hooked, how can traders use probabilities to make intelligent trading decisions?

The probability of profit (POP) is defined as the chance of making at least $0.01 on a trade by a specific date

First, they should understand that the probability of profit (POP) for a trade or strategy means the probability of making at least $0.01 on that trade by a specific date in the future, such as an option’s expiration. Profit and loss can and will fluctuate daily, but the POP of a given trade at expiration can be estimated based on current implied volatility levels, how many days remain until expiration and how much extrinsic value is associated with that trade. But before diving into that idea, consider how POP is calculated.

The math behind POP

In the simplest terms, probability of profit is an extension of the probability of an option expiring in-the-money (ITM) or out-of-the-money (OTM).

For short-option trades, POP will be greater than the probability of that option expiring OTM. For long-option trades, POP will be less than the probability of that option expiring ITM.

The reason is the option’s extrinsic value.

Extrinsic value is the portion of an option’s value that’s tied to time and volatility. It’s separate from intrinsic value, which is based on where the stock price is relative to the option’s strike price. The value of an out-of-the-money option is 100% extrinsic. Extrinsic value will be $0.00 at expiration, and the profit or loss of an option trade will be determined by whether or not it has intrinsic value at expiration. Short-option sellers want their options to have zero intrinsic value at expiration, and long-option buyers want as much intrinsic value as possible at expiration. Keeping that in mind, the discussion can turn to how probabilities start to unfold through the lens of extrinsic value.

Short-option sellers

Short sellers of option contracts benefit if the option expires OTM (which is completely opposite of long buyers of option contracts).The short seller keeps the credit received up front for taking on the risk — after all, the short seller has more theoretical adverse risk than the option buyer.

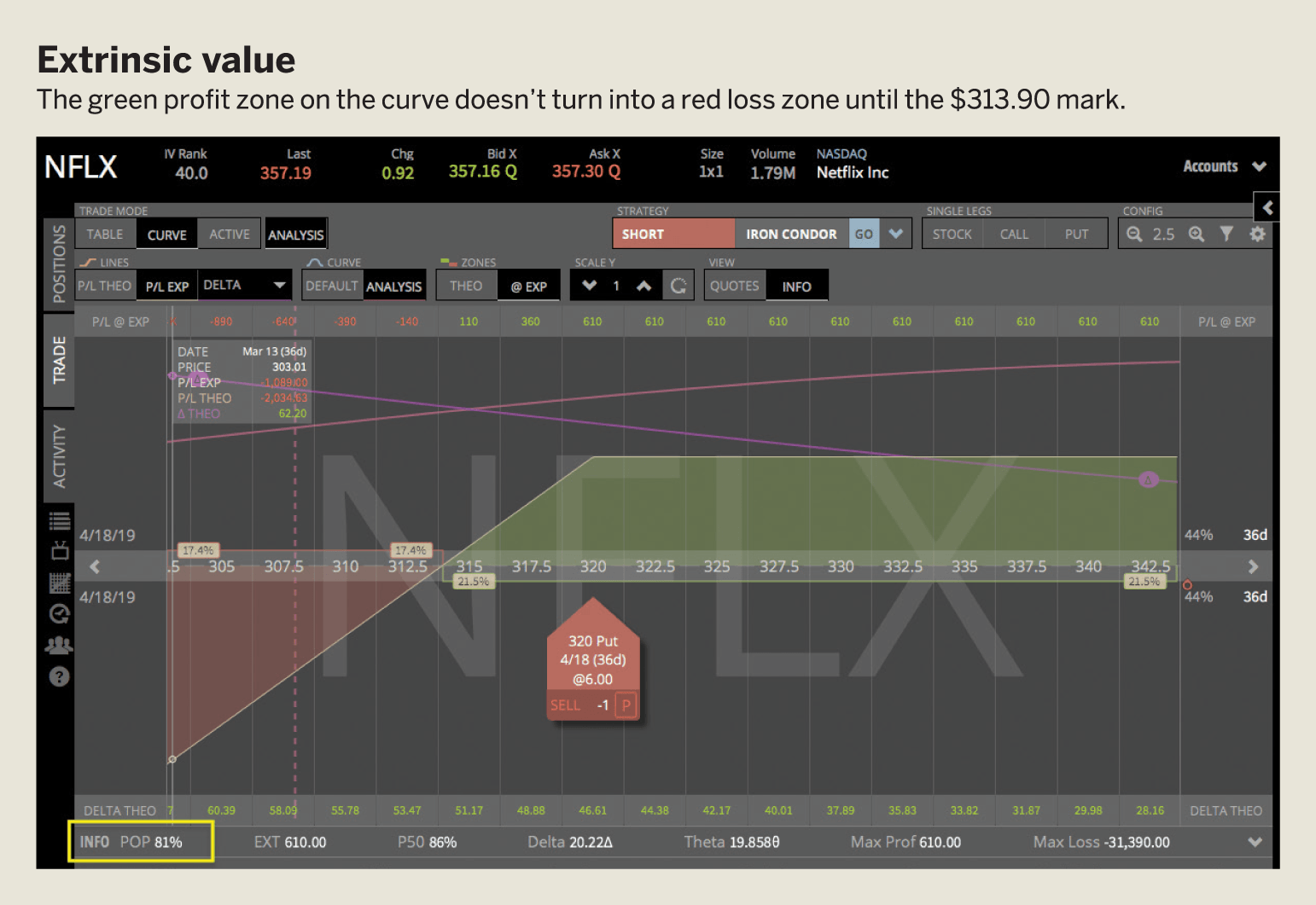

If traders feel bullish on Netflix and decide to sell a put at the 320 strike, they would collect a $6.10 credit for taking the risk of the stock falling below their strike of $320, where they would be obligated to purchase 100 shares at expiration. This credit is 100% extrinsic value at this point because Netflix is trading at around $357 per share and the strike is at $320 — it’s OTM. The probability of that option expiring OTM is 76% in this expiration cycle, but the probability of profit is actually higher than that at around 81%. (See “Extrinsic value,” below).

Why? The answer has to do with extrinsic value. The green profit zone on the tastyworks curve view doesn’t turn into a red loss zone until the $313.90 mark. That’s because the trader would have already collected $6.10 to open the trade, and that credit can be used to offset intrinsic value losses at expiration if Netflix is below $320. If Netflix were at $313.90 at the option’s expiration,the trader would be at break even on the trade (no loss or profit) because the option’s intrinsic value ($6.10) equals the credit received ($6.10).

Going back to the definition of POP, which is the probability of making at least $0.01 on the trade, it becomes clear why POP is a higher number than the probability of the strike expiring OTM. Because the trader collected an extrinsic value credit to open the trade, that value can be used to offset losses past the strike price to a point. The break even point of the trade ($313.90) is further away from the option’s strike price ($320). It’s less likely for Netflix to drop below $313.90 than it is for the stock to drop below $320.

Because of that, POP is higher than the strike expiring OTM for short option sellers, as that $0.01 profit point is below the strike in this example, at $313.9. In other words, short OTM option sellers can see profit at expiration even if the strike is ITM. This extrinsic value credit can do wonders for probabilities of success and can be thought of as a defensive mechanism just as much as an offensive mechanism.

After that crash course on why POP is higher than the probability of a short-option expiring OTM, the class can turn their attention to long options. Can extrinsic value help traders in the same way at expiration? Unfortunately, when buying options in most cases, the answer is a resounding “No!”

Long-option buyers

When buying an option to open for a debit, traders benefit most if the option expires ITM by more than they paid for the option initially. If that happens, the trader can sell the option for a larger credit than the debit they paid for it, and realize a profit.

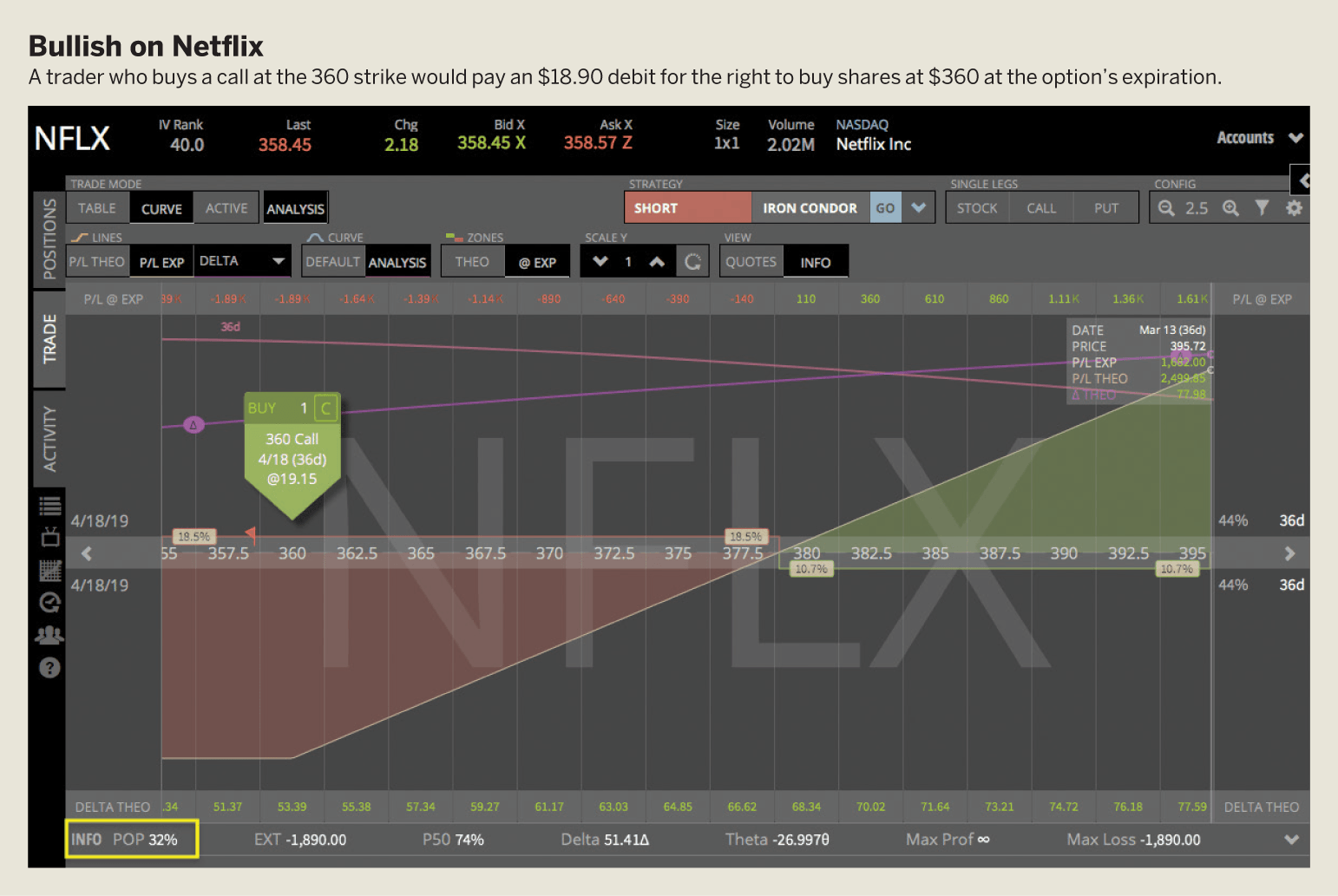

The chart in “Bullish on Netflix,” above, shows that if traders are bullish on Netflix and decide to buy a call at the 360 strike, they would pay an $18.90 debit for the right to buy shares at $360 at the option’s expiration. That debit is 100% extrinsic value at that point because Netflix is trading just under $360 per share and the strike is at $360. That’s not good for the trader at expiration because, as the image indicates, the green profit zone doesn’t begin until the $378.91 mark. If traders pay $18.90 for the contract, Netflix must be above the $360 strike by at least $18.91 at expiration for the trader to realize a profit. So, $378.90 is, as many readers will have guessed, the breakeven price of that long call.

Two investors can feel bullish about a stock like Netflix but have completely different trades and probabilities of success

The probability of that option expiring ITM is 47%, but the probability of profit is much lower than that at around 32%. Because the option must be significantly ITM for the trade to be at least $0.01 profitable, the trader wants the stock price of Netflix to move much higher. It’s harder for Netflix to rise above $378.90 than it is for it to rise above $360. Typically, when a big movement is needed in a specific direction in a short time, probabilities start to decline.

So what can a trader do, if anything, to mitigate the low probability of success at expiration associated with buying at-the-money (ATM) options? The answer has to do with extrinsic value, yet again.

Dealing with extrinsic value

Based on what’s been covered so far, it’s clear that paying for extrinsic value in a long option isn’t ideal if traders are holding the option to expiration. On the other hand, collecting extrinsic value in a short option can make the difference between profit and loss if the trader’s holding the option to expiration. If traders tie this together with POP, they should make the most of extrinsic value when selling options, and pay as little as possible when buying options. In a high implied volatility (IV) environment,extrinsic value could be higher than normal, and in a low IV environment, extrinsic value could be low. At the end of the day, implied volatility is directly related to extrinsic value because IV is derived from current option prices.

For short-option sellers, the tactic is easy to see — the more premium traders can collect up front for selling the option, the better off they will be in terms of breakeven price and POP. That might mean sticking it out and waiting patiently for high IV.

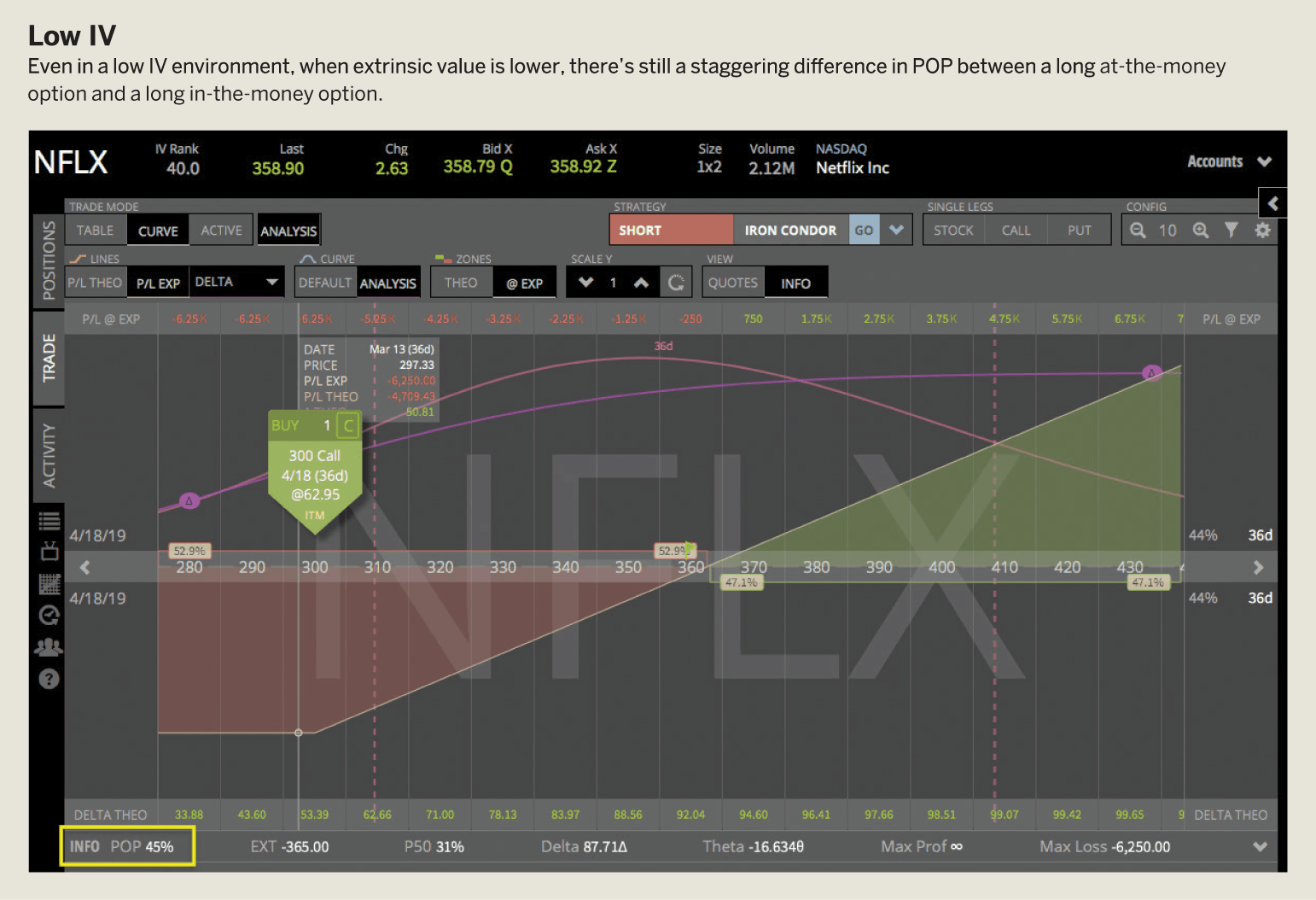

What this means for long-option buyers is paying more attention to the setup of the trade, rather than the environment. Even in a low IV environment, when extrinsic value is lower, there’s still a staggering difference in POP between a long ATM option and a long ITM option— take a look at the Netflix example in “Low IV,” below, to see why.

In that image, the trader is buying the $300 strike call instead of the $360 strike call. Yes, the option will be more expensive overall because it’s now ITM, but does that make it a higher-probability trade compared with the $360 strike call? The answer is yes, based on extrinsic value. When buying the 360 strike call, the trader would have paid around $18.90 in extrinsic value to own the option. Netflix would have to climb to $378.90 by expiration just for the trader to break even.

Buying the $300 strike call, the trader is paying $62.50 for the option, which has only $3.65 of extrinsic value. That’s because the option has $58.85 of intrinsic value with Netflix at $358.85. Because traders can maintain all of that intrinsic value if the stock stays at the same price, they no longer need for the stock to move up as much to be profitable on the trade at expiration.

Long-option buyers only need to make up for the extrinsic value they pay for the option to be profitable at expiration, and in this case it’s about 80% less extrinsic value than the $360 strike call. That’s clearly reflected in the difference in POP, which increases to 45%. Netflix only has to rise to $362.51 at expiration for this trade to be profitable compared to $378.91 in the earlier example.

And it’s easier for Netflix to rise above $362.50 than for it to rise above $378.90. The probability of Netflix landing at or above $362.50 at expiration is around 45%, and the probability of Netflix expiring at or above $378.90 is around 32%. Extrapolate that over a large number of occurrences, and the difference in potential success becomes huge.

Remember that options traders take risks with the objective of turning a profit. Regardless of how they arrive at a directional or neutral assumption, they should approach it in a methodical and intelligent way. For long-option buyers, that could mean minimizing extrinsic value as much as possible. For short-option sellers, that could mean maximizing it. After all, it could make the difference between profit and loss at expiration.

Mike Bulter, a self-taught trader, serves as host of Mike and his White Board and co-host of Market Mindset on the tastytrade network. @tastytraderMike

Mike Butler, Beginner, Strategy, Earnings, Expected Move, Expiration, Implied Volatility, Strike Price, Watchlist

Mike Butler, Beginner, Strategy, Earnings, Expected Move, Expiration, Implied Volatility, Strike Price, Watchlist

Most investors are familiar with what earnings are, but less know about the different strategies and considerations when investing in a company with upcoming earnings. In this post you will learn about what earnings are, the terminology associated with earnings, and how you can place an ‘earnings trade.’

Read More →

Mike Butler, Beginner, Strategy, Earnings, Expected Move, Expiration, Implied Volatility, Strike Price, Watchlist