Gold Doesn’t Rule

The bright yellow metal hasn’t kept pace with most stocks and bonds

As an investment vehicle, gold usually doesn’t glitter as brightly as equities.

To see why, let’s go back to August 1971. That’s when President Richard Nixon ushered in the era of widespread fiat currencies and floating exchange rates that we know today. He did it by withdrawing the United States from the international Bretton Woods system of gold-referencing exchange rates.

That meant the dollar’s official convertibility into bullion was formally ended, and it no longer benefitted from the built-in support of the “gold standard” system.

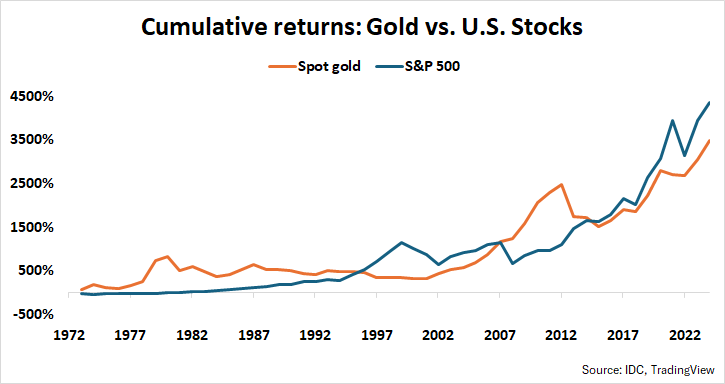

Since then, from 1972 through May 2023, the precious metal has lagged the bellwether S&P 500 equity benchmark of Wall Street performance by more than 870%. It rose just under 3,500% over that period, while U.S. stocks added slightly more than 4,360%.

Sometimes a “buy”

Nevertheless, gold has at times outpaced stocks. It appreciated faster than the S&P 500 from 2007-2014, when the global financial crisis and the Great Recession convinced the Federal Reserve to cut its benchmark interest rate to 0%.

That period highlights gold’s role as a tactical instrument instead of a “buy-and-hold” part of an investor’s portfolio. It speaks to the types of environments that tend to see the precious metal thrive. In modern markets, it typically trades as a foil for the path of interest rates and the U.S. dollar.

That makes intuitive sense. Gold confers upon its buyers a yield of 0%. Rising rates offering positive interest income streams on other assets make it unattractive by comparison. Similarly, a stronger greenback undercuts the appeal of an alternative store of value to fiat currency.

Investors dutifully obeyed this pattern as markets grappled with the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. Gold surged as the Fed slashed interest rates and launched an open-ended quantitative easing (QE) program—an effort to keep credit markets flush with liquidity by buying assets from institutions and thus injecting them with much-needed cash.

When this monetary largesse was matched with equally generous fiscal outlays, inflation followed. As it became clear that higher prices were becoming sticky, the Fed embarked on a blistering rate hike campaign in March 2022. Gold fell alongside stocks and bonds for much of that year, undermined by its absence of yield income and a rising dollar.

This calculus has now given way to something less familiar.

A new paradigm?

A blistering rally in the first quarter of 2024 saw prices punch through the top of a long-standing range of upside progress lasting for nearly four years. It was marked by the August 2020 high set just below $2,100 when the Fed hit the brakes on expanding the stimulus programs it had triggered in COVID’s wake.

Curiously, these gains played out while interest rates marched higher as markets responded to a run of hotter-than-expected U.S. economic data, which they interpreted as reducing scope for Fed rate cuts following the end of the tightening cycle. The dollar rose in tandem. Gold might have been expected to suffer under such conditions.

What’s more, data tracking the markets’ speculative appetite for gold suggests the absence of the kind of bullish upswell that might have accompanied the metal’s heady gains.

Futures positioning data that the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) publishes in its Commitment of Traders (COT) report shows net speculative longs languished in a range set from April 2023 even as prices soared. Meanwhile, gold holdings in the bellwether SPDR Gold Shares ETF (GLD) were sliding to a five-year low.

The dragon in the room

That gold became unresponsive to well-known macro forces seems to line up with the sense that speculative interest from global markets has not been the primary impetus for the latest round of price gains. Instead, this change in trading patterns might line up with China’s accelerated accumulation of gold.

The pace of buying by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) began to quicken in the second half of 2022 and ramped up to 11.2% year-on-year by the end of 2023, the highest in eight years. Ravenous uptake continued into 2024, albeit at a slightly slower rate. By April, 2286.23 tons of gold were held in reserve, up 9.5% year-on-year.

A report from BNP Paribas, a French bank, posits that Beijing has been motivated by its burgeoning trade with Russia. Sanctions following its invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 have cut the country out of the global U.S. dollar-based trade settlement system.

Russia suddenly needed to sell a lot of energy—its main export—outside the usual international channels. China, the world’s largest oil importer, obliged. Bilateral trade volume has surged, with transactions settled in Chinese yuan (CNY). To do that, Russia adopted China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS).

Beijing has been trying to grow CIPS as an alternative to the dollar-dominated SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) global payments system since 2018, in a bid to weaken Washington’s ability to weaponize access to the greenback. Russia’s predicament was a perfect case in point.

Building the spite store

This sudden infusion of trading volume saw the number of transactions on CIPS surge to 6.61 million in 2023, an increase of 50.3% year-on-year, according to PBOC reporting. The value of this business jumped to CNY 123.1 trillion (U.S. $17.3 trillion), an increase of 27.3% over the same period.

Chi Lo, a senior market strategist for the Asia Pacific region with BNP Paribas Asset Management (BNPP AM), argues that China’s gold binge reflects a desire to back this trade with bullion. That could entice would-be participants encouraged by Russia’s example but leery of dealing in fiat CNY, which isn’t fully convertible internationally, to join CIPS.

As of April 2024, China’s gold reserves amount to U.S. $168 billion. CIPS averages close to CNY 500 billion (U.S. $70.45 billion) in transactions daily, so this is enough to backstop about two and a half days’ worth of flows. If the system grows as Beijing intends, it will need to buy a lot more gold to realize its vision of a hard-backed SWIFT competitor.

It will probably take some years to determine whether China’s CIPS gambit will succeed. In the meantime, gold prices may enjoy a backstop underpinning their performance—and perhaps even amplifying it—despite wherever global interest rates and the U.S. dollar may be trending.

Ilya Spivak heads tastylive global macro and hosts the network’s Macro Money show. @ilyaspivak