The Serendipity Mindset

Luck? It’s all in your head.

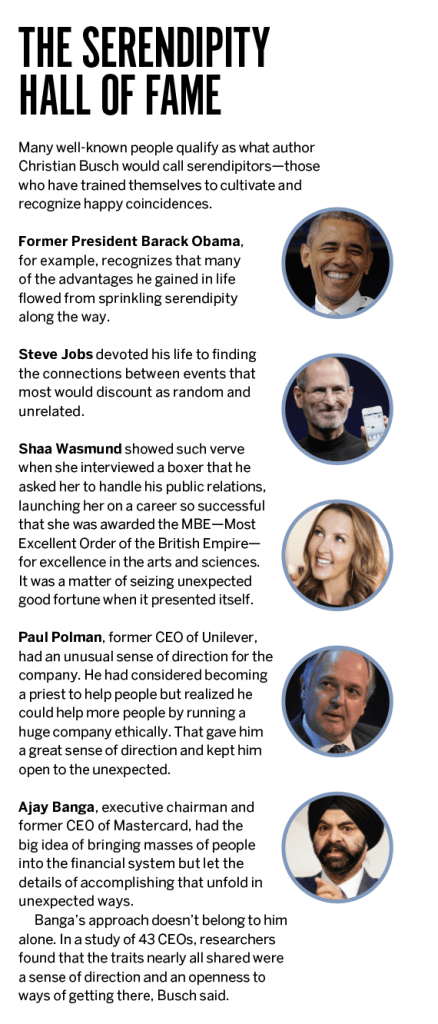

In his book The Serendipity Mindset: The Art and Science of Creating Good Luck, author Christian Busch differentiates between what he calls blind luck and smart luck. Some people find themselves blessed with blind luck, like the good fortune of being born into a prosperous family. Others work to achieve smart luck by recognizing and combining valuable opportunities and then acting upon them—what Busch calls “connecting the dots.”

Busch, who teaches at New York University and the London School of Economics, had been thinking about serendipity long before he wrote the book. “What I found fascinating is that this kind of positive coincidence seems to pop up everywhere,” he told Luckbox. “So I had this curiosity about it.”

For a while, he simply talked about serendipity with friends. But then a bolt of lightning struck. He suddenly realized serendipity could serve as the guiding principle for his next book about the future of business.

“So that’s how the book came about—as a serendipitous moment in itself,” Busch recalled. “My whole journey, in a way, has been serendipitous encounters working off of other serendipitous encounters.”

A mindset

For some people, serendipity doesn’t just happen. Many of the world’s most joyful and successful people cultivate the serendipity mindset. Think of it as a philosophy of life that anyone can adopt.

It requires opening oneself to the unexpected, casting aside preconceptions and envisioning connections among seemingly unrelated elements. It’s a shift from passive acceptance of events to actively shaping outcomes.

Busch provided the example of a California entrepreneur who found himself stranded in London when a volcanic eruption in Iceland grounded flights throughout Europe. Knowing some of his peers were also marooned, he organized a conference that attracted 200 attendees. Some 10,000 viewers watched the livestream. And he accomplished that over a weekend with no budget.

Faced with something random and unexpected, the entrepreneur had responded by capitalizing on his connections with businesspeople and organizations to create something positive, Busch noted, adding that things come together in seemingly unexpected ways more often than people realize. In fact, Busch finds so many examples of serendipity that he can categorize them.

Serendipity’s subsets

Busch identifies three types of serendipity and endows them with memorable names. He calls them Archimedes Serendipity, Post-It Note Serendipity and Thunderbolt Serendipity.

Archimedes Serendipity occurs when someone studies a problem but finds the solution in an unexpected way. “You have a destination in mind, but the way you get there changes,” Busch said in the book.

The classic case occurred when Archimedes, the Greek mathematician, was trying to figure out whether a crown was cast in silver or gold. The crown weighed the right amount, but would have to be larger if it contained silver, which weighs less than gold.

While visiting a public bath, Archimedes saw the water spill over the sides of a tub as he entered, and suddenly realized that if two crowns weighed the same amount, the silver crown’s greater bulk would displace more water than the gold crown’s smaller bulk. Problem solved.

The second type of serendipity is named for the ubiquitous Post-It sticky notes that adorn the partitions of so many office cubicles. It occurs when someone studies one problem but solves another one. “Your journey goes off into a completely different direction but still gets you to a destination you like,” Busch wrote.

In the namesake example, researchers at 3M were trying to develop a strong glue but accidentally formulated one that proved relatively weak. Still, the new adhesive found a home because it worked perfectly on Post-Its.

The third type, Thunderbolt Serendipity, strikes when it’s least expected because the beneficiary suddenly hits upon the solution to a problem that wasn’t even under consideration. Busch’s own experience with being struck by the idea to make serendipity the subject of his book serves as an example.

Although the categories help explain serendipity, Busch warns against overemphasizing them. Some serendipitous events defy categorization, while others blend the categories. In any event, dwelling on the categories can stymie serendipity by distracting from connecting the dots.

Extracting the positive

Even unpleasant events can become useful cogs in the mechanism of the serendipity mindset, according to Busch. He tells the tale of someone who spilled a latte on a fellow patron at a coffee shop. The person who caused the mishap could apologize and leave. Or the spiller could engage the victim in conversation and perhaps meet someone who becomes a business partner or the love of a lifetime.

So, it would seem that eventually everyone would take up the serendipity mindset. But serendipitors can meet resistance. They operate in a different way from the masses who revere planning and treasure control—even if that control’s merely an illusion. People often delude themselves into thinking that random events were part of their plan all along.

Busch harbors other ideas for conducting society. “Let’s validate the lifestyle of people who have an approximate plan, but who are also actually open to the unexpected and who mostly serendipitously create their own luck and luck for others,” he advised.

One of his goals with the book has been to convince CEOs and their board members to become more honest about the randomness of events and less protective of the facade of control they maintain to raise their status in the eyes of others. Informed by hindsight, people make up stories that turn a string of luck into a seemingly well-planned series of reaching goals.

“Let’s let serendipitors tell their stories in real ways rather than the ways we’re used to,” Busch urged. It’s a plea that’s resonated for readers. Since finishing the book, Busch has been contacted by serendipitors who’ve embraced its ideas. “Oh my God!” one reader told him. “You’ve described who I am, but I didn’t have a vocabulary for this.”

Creating a vocabulary for serendipity—as Busch did in the book—moves luck from the realm of the passive into the world of active pursuits where people can learn to shape outcomes. For many readers, having the right words to do justice to the “luck” they’ve worked hard to achieve lends credibility to the way they’ve lived their lives.

Navigating serendipity

Busch beseeches readers to build a serendipity “muscle” that takes advantage of the fact that smart luck is a process. Luck results from recognizing and acting upon serendipity “triggers” that can work together to bring about fortuitous coincidence.

The result—serendipity—constitutes a major force in the world. In fact, an estimated 30% to 50% of scientific breakthroughs result from the ability to capitalize on happenstance. Discoveries ranging from penicillin to Viagra occurred by accident when scientists were trying to achieve something totally different.

To achieve serendipity, begin by seeding every interaction with possible “dots” that can trigger coincidence. For example, one of Busch’s acquaintances was asked what he does. He replied that he’s a technology entrepreneur, has been reading the philosophy of science and really likes to play piano.

That response provides three possibilities to connect with the other person. It happened that the questioner’s sister was teaching the philosophy of science, and that led to a guest lecture for the acquaintance who had the foresight to lay the groundwork for serendipity.

When the dots connect that way, it’s time for tenacity to kick in and carry the serendipitor to good luck through hard work.

But what if hardships arise? Serendipitors like Barack Obama have a knack for reframing a crisis as an opportunity, Busch maintained. That can keep one going long after others would have thrown up their hands in desperation, he said, adding that, “If you want a happy ending, you can’t stop the story too early.”

Another key to serendipity lies in understanding the other person’s motives. In one example, a spouse’s complaints about where one leaves a toothbrush could actually reflect a feeling of being held in disregard because of the failure to move the toothbrush after three requests.

In companies, people often talk around a problem or a goal, making it difficult to grasp where the enterprise is headed, Busch continued. “A lot of times there’s ambiguity, and a lot of times we can’t put everything exactly into words,” he said.

That’s why Busch advocates using the Socratic method of seeking to ask better questions about underlying assumptions. Asking the question “why” can accomplish a lot, he maintains. After all, everyone involved stands to benefit.

“There’s been a big shift towards enlightened self-interest,” Busch noted. “The idea is that the more you can cater to others’ needs, the more others also want to cater to your needs. In more collaborative settings and in a networked world, that is increasingly the case.”

That attitude generates good karma and simply feels really good, too, he continued. It even creates an atmosphere where everyone involved deserves the benefits of serendipity, according to Busch.

Everyday approaches to serendipity

Can people simply get up tomorrow morning and begin to court serendipity? In Busch’s view, they can. He recommends keeping a serendipity journal to record good fortune. Begin the diary by writing down principles and describing a life destination. Then incorporate that destination into every conversation to set the stage for coincidence.

The journal also helps the diarist recognize moments of serendipity that have occurred. That reveals the underlying patterns that one can repeat to bring on additional serendipitous situations.

Journaling also points out missed opportunities for serendipity, like the time an idea popped into the diarist’s head during a meeting but wasn’t spoken out loud and thus never came to fruition. That can uncover patterns that one can break. Fear of rejection, for example, may have blocked the urge to speak up at the meeting, and that’s a problem one can address.

In the workplace, teams can hold project funerals to assess what went well and what went wrong. Sometimes, those funerals reveal a new way of thinking about the work that’s been done or a new way forward as the work proceeds.

People might prefer to talk about success than failure and thus may shy away from project funerals that dredge up the details of a less-than-successful effort. But discussing what went wrong offers more opportunity for learning than will emerge from the autopsy of a project that succeeded.

If the discussion at a project funeral leads to a new way of thinking or a new use for an existing product, observers may view the process as producing a piece of luck. But it’s a case of creating the atmosphere that breeds luck.

At meetings, Busch likes to ask questions like, “What surprised you last week? Was there something in the data that was unexpected? And why was that the case?” Once again, he’s laying the groundwork for recognizing the right kind of coincidence.

At a Chinese company, for example, customers were complaining that the firm’s washing machines were breaking down. Investigation revealed the farmers were using the machines to wash potatoes instead of clothes.

That unexpected bit of information could have prompted the company to try to teach the public the purpose of its product. Instead, the company set about creating a machine capable of washing potatoes.

“We can teach people to watch out for the unexpected because a lot of times innovation comes from those places,” Busch said.

Resisting serendipity

Many common habits stand in the way of achieving serendipity, Busch noted. So many people have a tendency to seek order in the face of chaos. Job seekers, for example, often shape a resume into a coherent narrative that chronicles the upward trajectory of a well-defined path to the executive suite.

But how often does that kind of resume amount to little more than a rear-guard action to impose structure on a fairly random career, Busch asked. He regards it as “post-rationalizing” that gives the impression the job candidate had more control than was actually the case.

Another impediment to serendipity arises with the tendency to hold oneself back from executing on projects. For Busch, that can take the form of the “inner imposter,” the notion that he’s not really good enough for the roles he’s chosen in life.

But there’s nothing like serendipity for banishing those negative feelings. After all, serendipity—as Busch lays it out and examines it—goes a long way toward explaining what’s right about the world.

Serendipity Probability

IG Group, a U.K.-based trading platform, has agreed to pay $1.1 billion for tastytrade, the online financial network and brokerage that owns Luckbox magazine. Management will stay in place at both firms.

That’s big news here, but it’s not the first huge accomplishment for tastytrade co-CEOs Tom Sosnoff and Kristi Ross. (See “above.”). In 1999, they helped start the thinkorswim trading platform, which they sold 10 years later to TD Ameritrade for $750 million.

What are the chances of launching not one but two stunningly serendipitous successes? For perspective, Luckbox turned to regular contributor Fergus Simpson, a senior researcher at Prowler.io who holds a doctorate in astrophysics from the University of Cambridge.

Investors are always on the lookout for the next Facebook, Uber or Twitter—a “unicorn” startup valued at more than $1 billion, Simpson said.

Identifying those companies early on is hugely rewarding. But how hard are they to find? And does their rarity live up to their mythical status?

Some 233 unicorns are alive and well in the United States at the moment, up 47 in 2020. That might seem like a lot, but their ranks are dwarfed by the huge number of new businesses that crop up each year.

If one picked a start-up at random, what are the chances it would ultimately become a fabled unicorn? To answer, compare the number of startups that emerge each year with the number of unicorns that appear each year.

Back in 2013, when the term “unicorn” was coined, the odds were longer than one in a million. It’s tricky to appreciate the magnitude, so it’s useful to describe long odds in terms of rolling dice. Here, it’s equivalent to the chance of throwing eight dice and ending up with eight sixes.

Try it at home, but be forewarned: Even when re-rolling nonstop every couple of seconds, it would usually take more than a month to achieve that perfect set of eight sixes. But one never knows—it could come up on the first try. That’s what investors hope.

These days, unicorns have become more prevalent than in 2013, meaning that throwing six dice would be the new equivalent.