Politics Has a Futures Market

In prediction markets, traders wager real money on political events. Here are some tips from the pros

What are prediction markets?

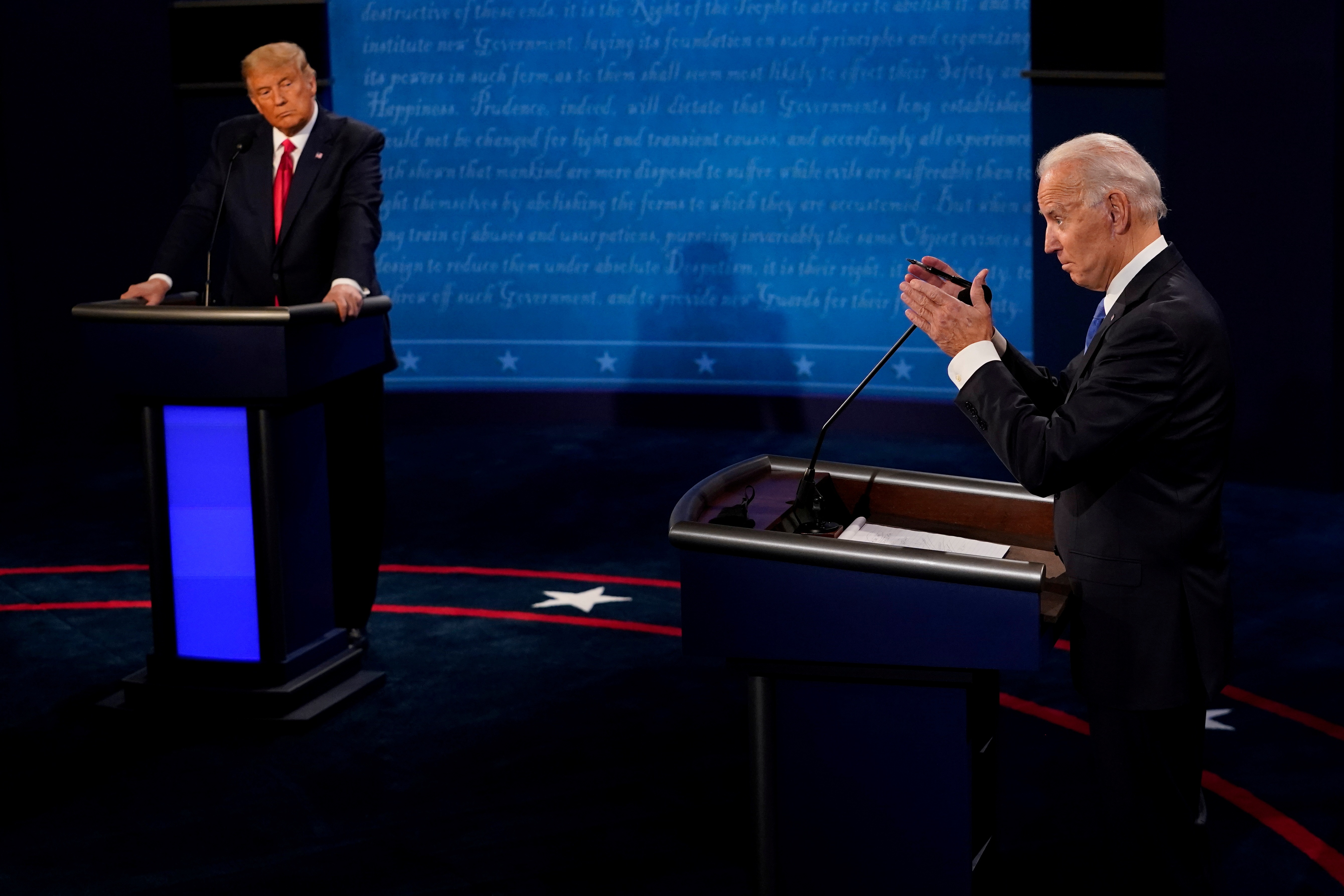

Prediction markets operate much like futures markets, except traders buy stakes in future political outcomes instead of commodities, such as foreign currencies or indices. For example, “Who will win the 2020 U.S. presidential election?” could be a market. In that market, traders would be able to buy “Yes” or “No” shares on individual candidate contracts.

Prediction markets may indicate whether the wisdom of the crowd, paired with the potential of winning or losing money, is more accurate at forecasting political events than traditional methods of measuring public opinion, such as polling.

Whether or not they actually are more accurate has been the subject of a lot of academic research. A 2008 International Journal of Forecasting study, for instance, compared market predictions to more than 900 polls in the five presidential elections between 1988 and the date of the study. It found that “the market is closer to the eventual outcome 74% of the time.”

Where are people predicting?

While the Iowa Electronic Markets (IEM), one of the first modern electronic prediction markets, has operated since 1988, its popularity—at least among traders active on social media—is eclipsed by predictit.org. PredictIt, opened in 2014, is run by Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, and like the IEM, it received a no-action letter from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to operate legally for academic purposes.

Every year, the number of traders using PredictIt has grown in the tens of thousands, Will Jennings, the site’s head of public engagement, told luckbox. About 100,000 users have made a trade in the last 90 days, and as many as 200,000 have signed up on the site.

How do PredictIt trades work?

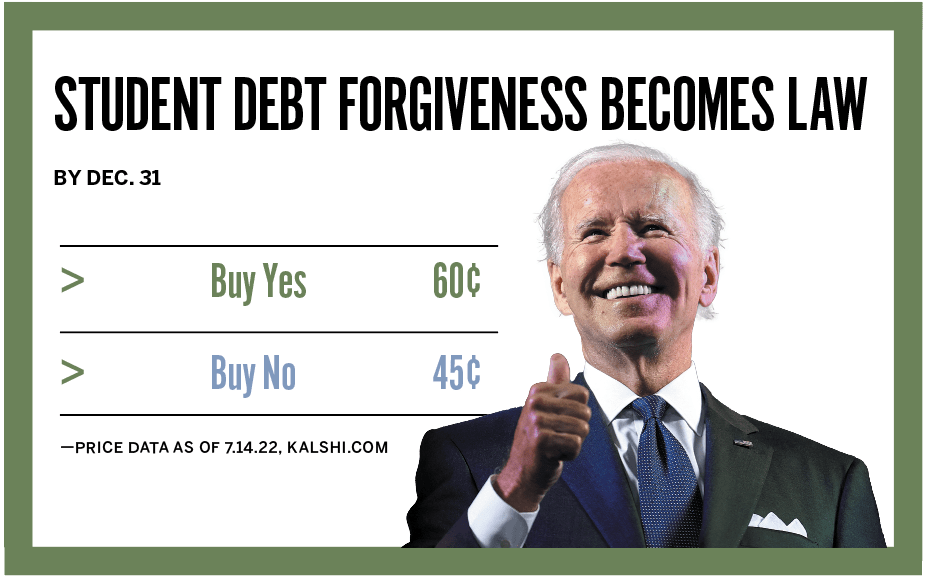

It’s not complicated. After signing up on the site and funding an account, traders may begin forecasting on any of PredictIt’s more than 200 markets. Markets may be structured with single or multiple contracts, depending on what they’re trying to forecast, but every contract is broken into binary “Yes” or “No” options. Upon expiration, correct contracts pay out 100% and incorrect contracts become worthless.

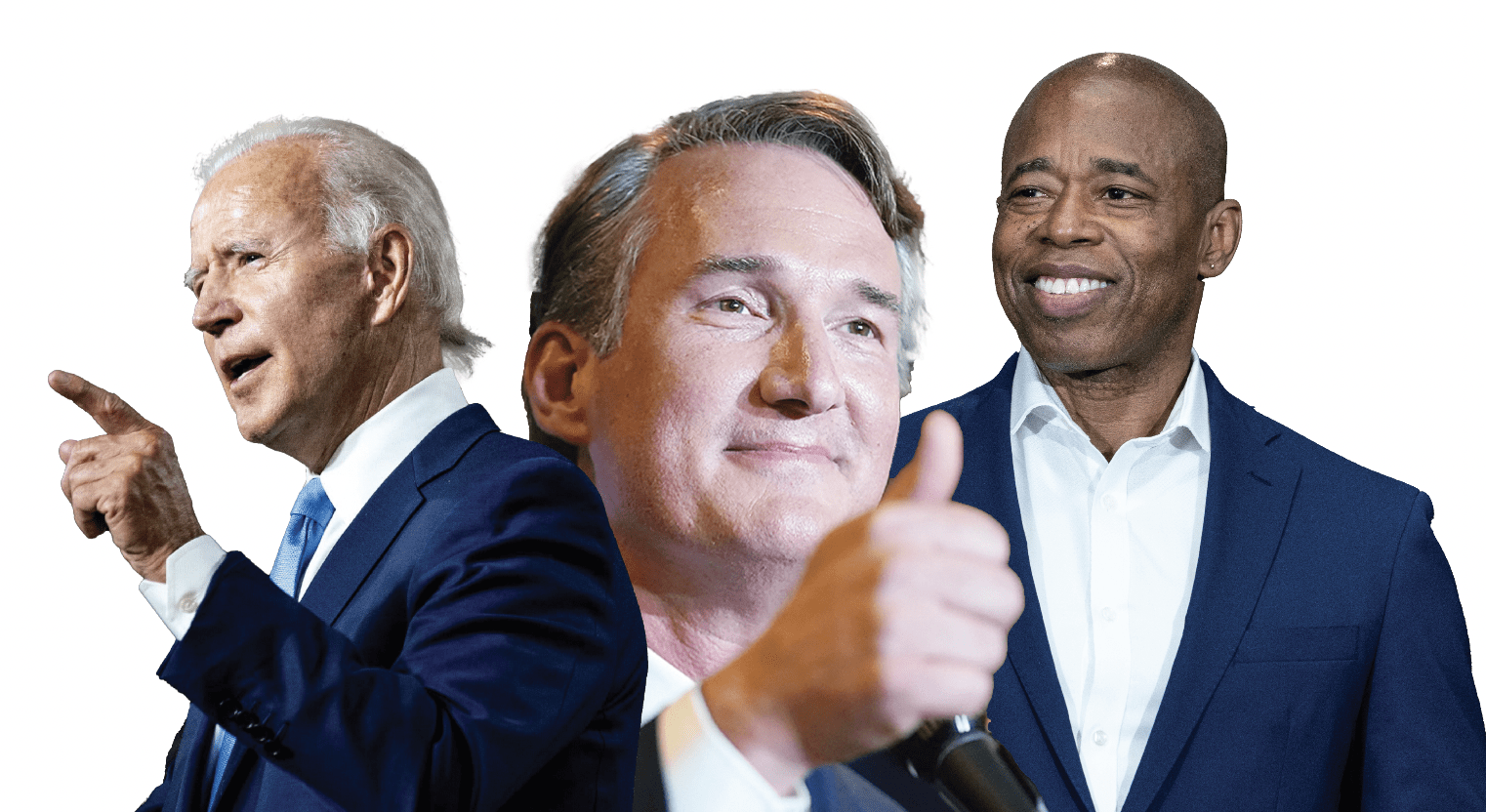

As far as pricing is concerned, every correct contract pays out $1, and contract prices reflect the market’s forecasted probability that an event will—or won’t—occur. For instance, if the aggregated opinion among forecasters is that Joe Biden has a 20% chance of being elected president in the “Who will win the 2020 U.S. presidential election?” market, a “Yes” share should cost somewhere around $0.20 and a “No” around $0.80.

PredictIt’s maximum bet on a contract in a market is $850, and the site limits the number of traders allowed to bet in each market to 5,000. While that number has been reached in some markets, the volume of traders regularly trading in and out of them means hitting the cap is usually short-lived. PredictIt charges fees only on profits and withdrawals. When shares are sold for a higher price than paid, PredictIt takes 10% of the profit, and upon withdrawing funds it charges a 5% fee for processing, according to the site.

With a presidential election just around the corner—what Jennings refers to as the “bread and butter of political prediction markets”—anyone with a hunch about what may be in store can put their money where their mouth is.

To explore some strategies for jumping into the world of prediction markets, luckbox talked to two PredictIt regulars about their experiences placing bets.

Retired Los Angeles-based stagehand Scott Supak is a longtime prediction market trader, having made his first trade in 2004 on InTrade, a defunct prediction market. Supak said he spends about four hours a day five days a week researching and making trades on PredictIt—but most of that time is spent on researching.

“I cannot stress enough how much you have to do your homework,” Supak said. “People come in and they bet on things without ever having even looked into it.”

In the last year, Supak, who doesn’t consider himself a full-time trader, said he made close to $10,000 forecasting on PredictIt.

“You spend a lot of time just sitting here, watching TV, doing what you would otherwise be doing anyway, just waiting for something to happen,” Supak said. “That can’t really be considered work. For the amount of time you put in, it’s pretty rewarding, frankly.”

For strategy, Supak champions a healthy balance of knowing the subject matter, knowing himself and knowing how to take advantage of the markets.

“You have to be good at all the political information—the fast information game. You have to be good on Twitter, you have to know who to follow, you have to do all of that kind of work,” he said.

Besides the basic homework, traders should also avoid the mistakes that cost gamblers money. “There’s gambler fallacies, there’s all these biases, there’s all these things that you’re not even sometimes aware that you’re suffering from,” Supak said. “Losing money will teach you fast.”

Instead, he uses the negative risk strategy—when a trader buys “No” shares in more than one of a market’s contracts at cheap enough prices to almost guarantee making money.

“We don’t even care who wins—it doesn’t matter to the negative risk people,” he said. “If you’re just buying ‘No’ shares in every contract, you’re essentially just providing liquidity to the ‘Yes’ buyers. But I do it in a pricing scheme that allows me to instantly make money off the arbitrage.”

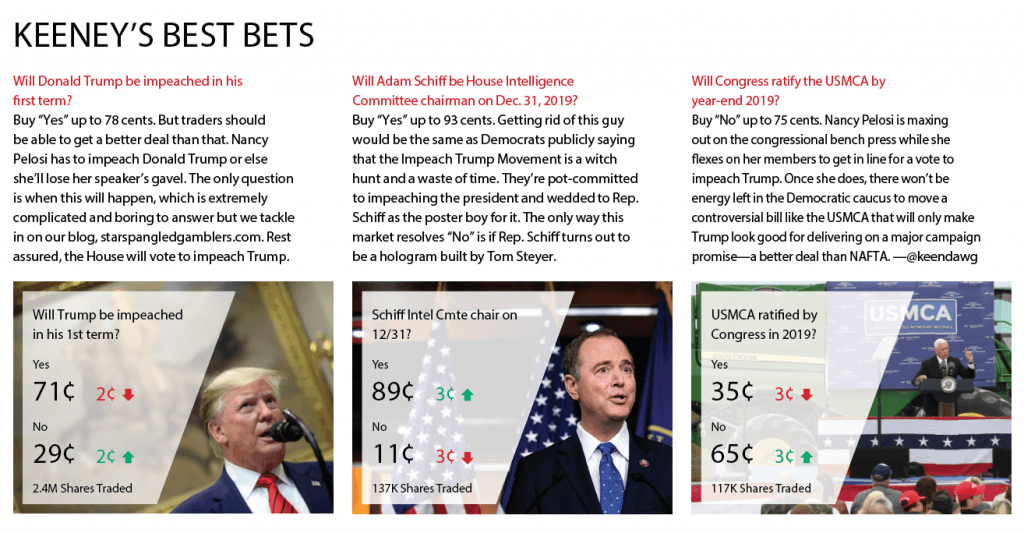

Another PredictIt trader, Alex Keeney, is known as “Keendawg” to followers of his Star Spangled Gamblers blog and podcast. He uses qualitative strategies informed by his experience working in politics and has been trading on PredictIt for a little over a year.

“My background is political, and my background is very communications-focused,” he said. “Where I’m the strongest is anticipating the behavior of Congress and anticipating the behavior of politicians.”

Keeney said he makes trades multiple times a week and often trades out of contracts rather than seeing them through to their closings because of the risk of sudden, unexpected reversals. Contracts, he said, usually follow a linear course, and once they get close to a 90% probability, he likes to cash out.

But if there’s one thing everyone involved with PredictIt seems to share, it’s the belief that anyone who really wants to put in the effort to do well in forecasting should strive for a better understanding of politics and political goings-on.

Sounds a lot like trading in financial markets.