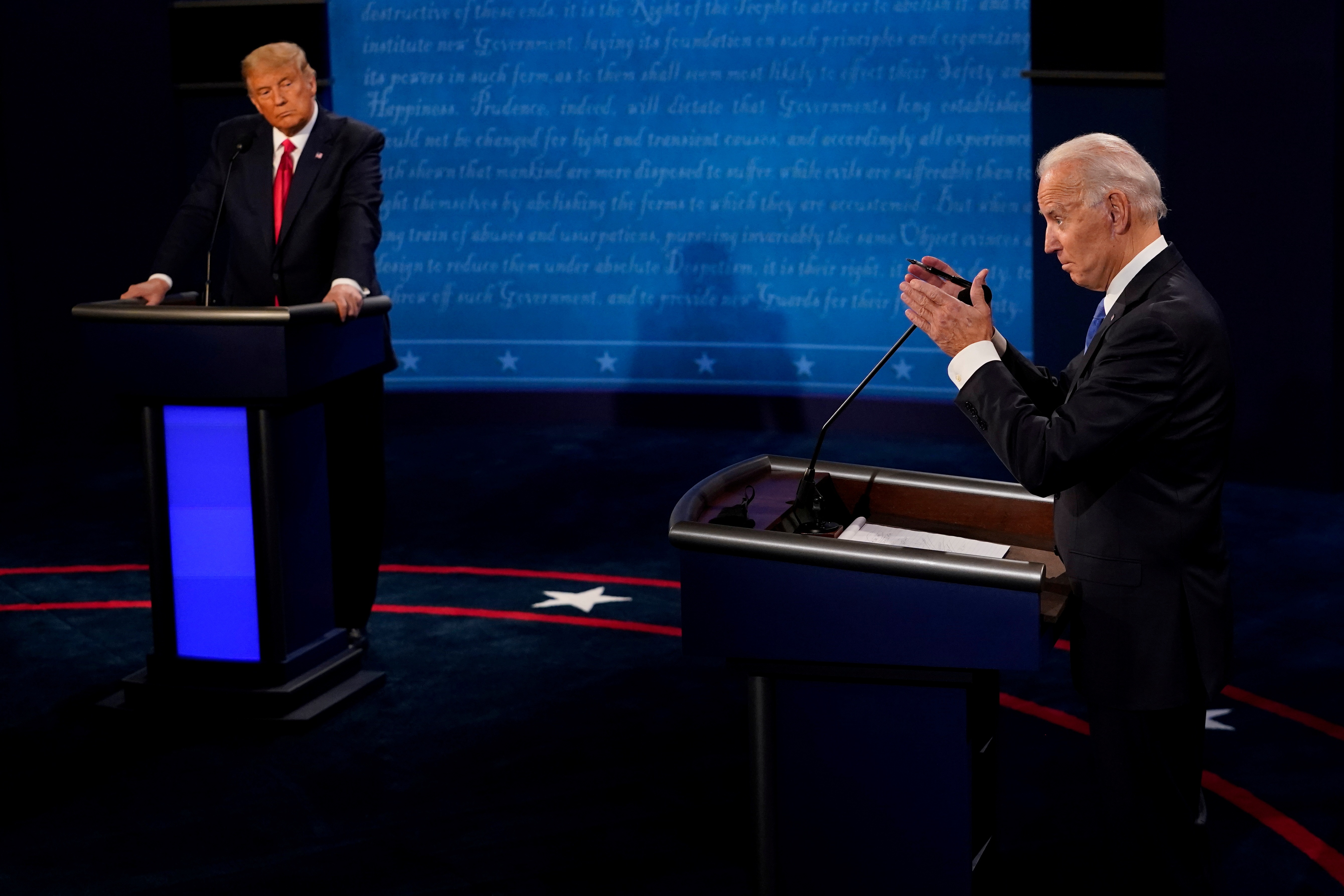

The Pollster Who Nailed 2016 Says the Polls Are Wrong, Trump Will Win

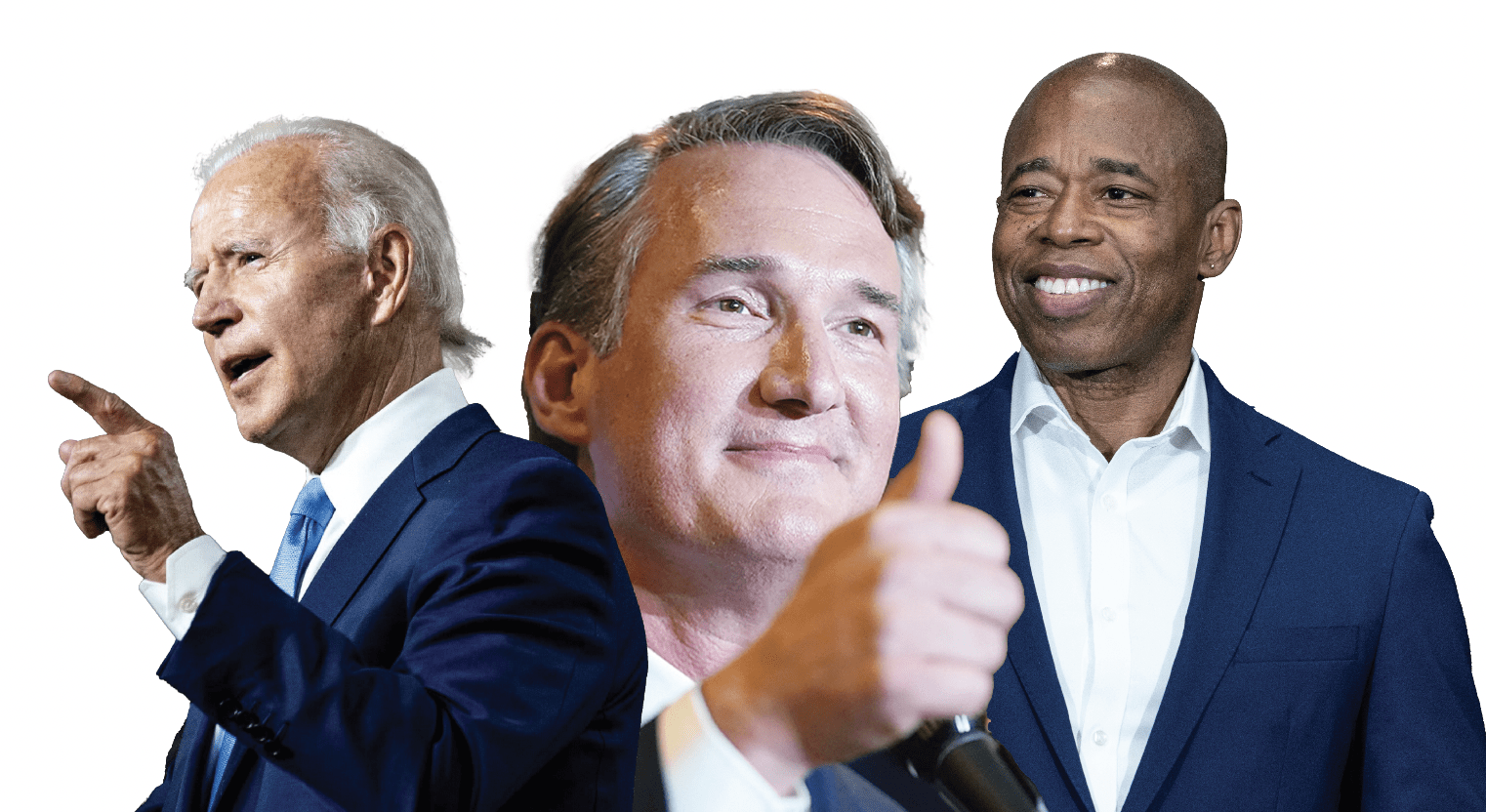

Social desirability bias has created a shy Trump voter effect, Trafalgar Group’s chief pollster Robert Cahaly says. The result? Trump could fare much better on election night than most polls suggest.

Despite receiving seemingly endless criticism, Robert Cahaly’s track record as a political pollster speaks for itself.

He and his polling company, Trafalgar Group, had the last laugh in 2016 when they correctly projected Donald Trump’s general election victories in Michigan and Pennsylvania—outlier forecasts among a sea of polls favoring Hillary Clinton.

Where other pollsters got it wrong, Cahaly said on The Political Trade podcast, is they didn’t account for social desirability bias, or a hesitation by poll-takers to share their true voting intentions out of fear of being judged.

That bias, he said, is just as prevalent in 2020 as it was in 2016, and possibly even more so. A glance through social media—or at Trump’s latest approval ratings—serves as a constant, glaring reminder that supporting Trump’s re-election is far from popular.

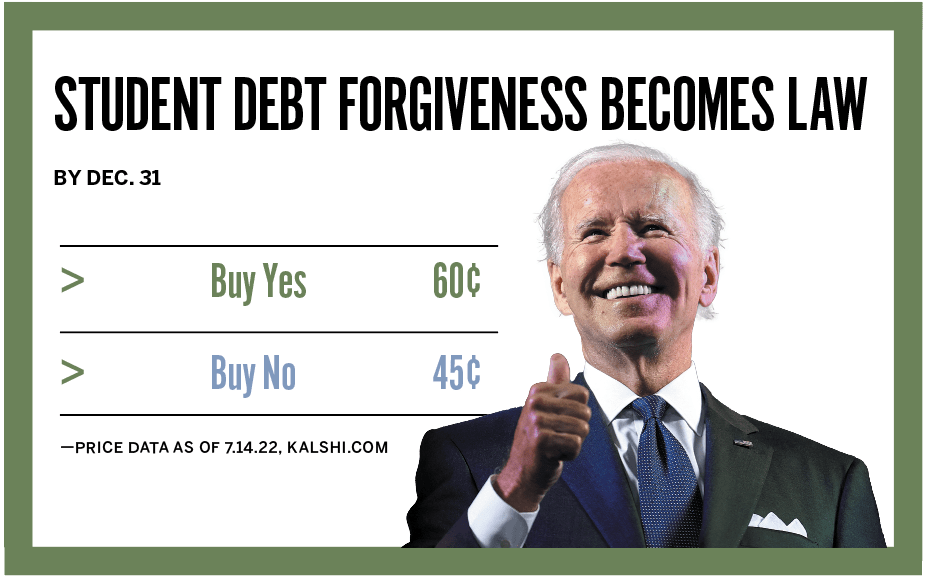

In his interview on The Political Trade, a podcast geared toward traders wagering real money in political prediction markets, Cahaly recommended a trade in PredictIt’s “What will be the Electoral College margin in the 2020 presidential election?” market.

His wager? Buy the GOP to win by 30-59 Electoral College votes.

In addition to sharing insights into how and why he came to that number, Cahaly shared a glimpse into what makes his polling operation different from the competition.

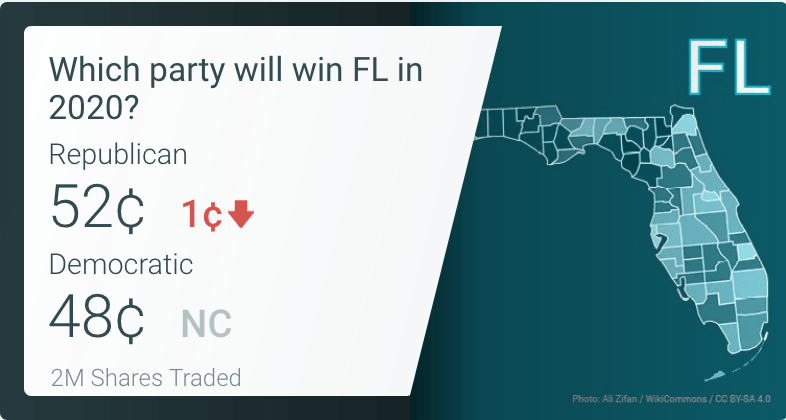

He recommends 10 trades in all, including markets for four swing states and two Senate races.

Cahaly’s exclusive interview can be heard in full here.

Below is an edited excerpt from Robert Cahaly’s appearance on The Political Trade.

Jeff Joseph (Host of The Political Trade)

In 2016, you clearly made a mark. You were the only pollster who called Trump to win Michigan. You called Trump plus two points. The final spread, of course, was really tight: under 10,000 votes and about three tenths of 1%. But the next closest poll to you had Clinton up five points. So, you were way out in front of anybody being close to that contest and the only pollster who actually called Trump to win Michigan. And then, moving on to Pennsylvania, Trafalgar Group had Trump plus 1%. He ended up winning by seven tenths of 1%. The RCP average had Clinton favored by 1.9%, 2.6%. away. Morning Call, which is of course a very highly rated poll over at FiveThirtyEight, and other platforms had Clinton up 4%. So, a big difference between Morning Call’s final poll going into the Pennsylvania election and yours. You were about 4.7% apart. And of course, you were within three tenths of 1% of the final outcome. Going back in 2017, you were the only pollster to correctly call the Georgia 6th special election. And then, according to our data, your success continued in 2018 rather dramatically. In Florida, you were one of the few pollsters whose data showed Ron DeSantis beating Andrew Gillum in the governor’s race, and Rick Scott beating incumbent Democrat Bill Nelson in the senate race that year. And of course, your call was DeSantis plus three. The RCP average had Gillum plus 3.6. So, over six-and-a-half points away was the consensus RCP average from your call. And large polling groups like Emerson had Gillum plus five. Harris had Gillum plus four. Quinnipiac had Gillum plus seven, way off from the final outcome. So again, Florida was a great state for you in 2018. Also, in the midterms, you had Claire McCaskill beating Josh Hawley in the Missouri Senate race. The NBC/Marist poll had McCaskill, the popular Democratic incumbent, up 3%, but at Trafalgar, you had Hawley plus 4%. And he went on to win by 6%. So, as a result of all this, an RCP story in June concluded that the Trafalgar Group has emerged from the last two political cycles as one of the most accurate polling operations in America. So, tell me, where or why were the other polls so wrong in 2016?

Robert Cahaly

Well, it boils down to two things, and to me, they represent an old-fashioned way of doing this, and we are an industry disrupter for a reason. And part of it is we try to recognize the real world that we live in in this day and age. And the systems are based on two fundamentally flawed principles: First, the highly rated pollsters—and “highly rated” I say tongue in cheek—but the people who rate pollsters and yet get election wrong, the highly rated pollsters are the ones that use the live calls. Well, there is a thing called the “social desirability bias.” For a person to express that they’re for a candidate to a live person, you end up with a situation where people say they don’t feel comfortable telling someone they’re for that candidate for fear of being judged for being for that candidate. It was clear in the Donald Trump race that they were called deplorable and everything else. So, these live callers are going to get that wrong. They just don’t measure it right because people want to be liked. People try to be polite. I always say, you know, if you ask a little child with a face full of crumbs, “Did you eat the missing cookies,” he’s going to do a little calculus in his head. “No, I did not.” I mean, he’s not going to tell you the truth. He’s going to tell you what he thinks you want to hear that the answer will get him in the least trouble. And I don’t think we get better at that when we get older. So that’s a big problem. It’s the reason that not only were their polls wrong, but it’s the reason that the exit polls were wrong. We still see people quoting from 2016 exit polls, which, if you remember, had the guys in the newsrooms kind of dancing and at 6:00 on election night because they were all saying Hillary was going to win big. If you won’t tell the truth on the telephone, what are the odds you’re going to tell the truth to a kid with a clipboard or an iPad standing in front of you? So, first is the amount of live interaction, live callers.

Jeff

Before we move on, let’s speak a little bit to the background there. The notion of a social desirability bias is a bias that’s been identified going back to the 1950s. Crowne and Marlowe did the most comprehensive work on that in the Journal of Consulting Psychology in 1960. And then, more recently in 2014 over at UMass, professor Ray La Raja wrote a thesis that basically said that people holding perceived unique political views are far more likely to withdraw from a political discussion and make public declarations for candidates in order to avoid the personal cost of being exposed. The concept itself that you’re referring to, the social desirability bias, has its roots in the Bradley effect, which was a theory which evolved after observed discrepancies between the voter opinion polls and election outcomes where a white candidate and a non-white candidate run against each other. And it was of course named after Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, the African American who lost in the 1982 California governor’s race despite being ahead in voter polls going into the election. Everyone thought he was going to be winning, and then there was another validation of that notion called the Shy Tory factor. It’s the name given by the British opinion polling companies when they first observed this phenomenon back in the early 1990s. And it was basically where there was a share of the electoral vote that was won by the Conservative Party, known colloquially as the Tory party, it was significantly higher than the equivalent share in opinion polls. And they basically came to the conclusion that these shy Tories were out there and that they were as much as 3% to 4% of the differential in 1992 and as much as 6% of the differential in 2015. YouGov Populace and other major polling firms in the U.K. have since sought to correct for this social desirability bias. So, I guess that’s what you’re referring to when you refer to this differential that you’re correcting for. We’ve heard you explain this as being the “Shy Trump voter.” So that that begs the question, if there was a shy Trump voter in 2016, first of all, were you able to quantify it?

Robert Cahaly

Yes.

Jeff

And then the follow-up question to that would be, what do you think that looks like today in this race?

Robert Cahaly

OK, well, let me start with my first exposure to it. I grew up in South Carolina, and growing up in South Carolina, we got a lot of bleed over from North Carolina. And so, my first exposure to this concept was with Jesse Helms. In Jesse Helms’ races, people would always say, “If Jesse’s only losing by two or three points, he’s going to win.” So, you know, it was called the Bradley effect, the shy Trump voter now. We always called it the Helms factor. And so, it was something that I grew up understanding pretty clearly, and watching and in practice in at least two cycles when I was very formative. Now, the way I was taught, and I would love to say I thought of this, but I did not. There’s a great fella who did a lot of polling that I worked with, and his name was Rod Shealy. He passed on a few years ago, but he was in the School of the Lee Atwaters. They were contemporaries in South Carolina, and politics. And Rod was always talking about “You’ve got to ask—when it’s really controversial—ask what most of their friends and neighbors think.” Then you look at what the difference is. And so, what we were doing was we used the friends and neighbors thing. And then we’d say, “All right, now, how do you think most of your friends and neighbors are voting? Which side are they on?” And we get that answer. And what we found across the board, Hillary always went down, Trump always went up. It was never the other way around. It was completely perfect. And that ratio of one went down, one went up, it was always Hillary down, Trump up. Now, how much of a difference depended upon the state. And so, what we did is, we kind of built a little formula. And what we like to do is, when we put out a final poll in a race, we tend not to put undecideds on it. We make the calculations, because most times, and we polled it many times, which of the undecideds are going to stay home, and how the others are going to break. And then we integrate our philosophy of where we think the shy voters are. And we’ll get more into how we do our surveys to avoid the social desirability effect or to minimize it—we can’t avoid it completely—but when we do that final calculation, we put that into effect. So, for example, if we saw that in a state, Hillary was dropping four, and Trump was coming up four, and it was almost equal, I mean, like whatever she was dropping, Trump was coming up. It was very rarely anything different than that. So, if she was dropping four, Trump was coming up four, then we’d measure that and see what the difference was, and we built a little system that calculated those in and figured out the differential, and it was more complicated to split the difference because it had to do with a lot of the factors of who was saying it. Like, we rated people. We also did that and we put a list of who we were calling a little different than most people, because we considered what we called a “Trump surge universe.” And those are people who had been very unlikely to vote, but still hadn’t moved and hadn’t died. We came up with 57 factors that might make someone a potential Trump surge voter, and you had to have like 20 or so for us to put you in the list. So, if we found those people, they would be weighted more than somebody who was not like a surge voter, because we knew they definitely were going to lean more toward voting for Trump. But we built a calculation where we basically take the two numbers, put it through our little system we built, and then predict how the undecideds would rank and how the final number would be.

Jeff

Well let’s go back to a question I asked earlier, which was if you were to look back and say, “OK, in 2016, in the general election, we quantified the shy Trump voter effect, which is a more contemporary designation of the social desirability bias, at what percent?”

Robert Cahaly

It was different in every state.

Jeff

And what was the range?

Robert Cahaly

The difference in what they were saying was between three and nine. We found the difference in what we predicted between three and seven.

Jeff

And how would you compare that then to 2020?

Robert Cahaly

Well, let’s look at it this way: In 2016, it was awful when Hillary Clinton said that Trump voters were despicable. That was a terrible name to call them. Now, let’s consider, are the names worse in 2020? I think they are. I think they’re “white supremacists,” “sexist,” “racist,” almost everything you can think of. And in 2020, have people been more shamed and doxed and hounded and harassed for their political opinions? Yes, they have. So, I do think the effect is here, yes. And I think it’s a lot bigger than anybody realizes. I think there are a lot of people in this country, and we hear from them all the time, who say, “I’m not saying anything at work. I’m not saying anything on social media. I’m not telling anybody that I don’t know really well what I think, but I’m going to vote. I’m not going to want to be one of those people who gets attacked and loses their job because I say that I’m for the president.” I hear it all the time. And let me go to something that’s important: Florida. Florida is a great case study in 2018, because there was not a social desirability bias at all in the U.S. Senate race. And there was a significant one in the race for governor. It’s not every race that these appear into. And so, with Gillum, people felt like the more politically correct answer would be to say they were voting for him. But we found that if you said you were for Scott, you were for Scott. If you said you were for Nelson, you were for Nelson. So, it’s not every race. You find this effect when people feel like they’re going to be judged for saying something different. We also find this effect on what people say about how they really feel about COVID, how they really feel about the Black Lives Matter organization versus that phrase. The phrase is universally popular. The organization, not so much.

Jeff

OK, well, understood, Robert. So, let’s open up that black box a little bit and try to get a better understanding of how you correct for this social desirability bias. What can you tell us about that?

Robert Cahaly

I want to go back. The second thing, because we had talked about the first was social desirability, because the next one comes into it. And the next one is about these ridiculously long surveys. Part of correcting for social desirability bias is getting regular people to take your polls, and we live in a day and age where people have lives. They’re busy. And when I see these polls that are 30 and 40 questions, 60 questions, 70 questions, 108 questions, I have one simple question: Who’s taking these polls? Do you know anybody who’s got 25 minutes to be interrupted on a Tuesday night? No. So what you have in those circumstances are when they do use regular voters, they find a voter that cares way too much. You know, they talk about low-information voters win elections. Well, if you’ve got that much time to talk about politics, you ain’t low-information anymore. You’ve probably got too much information, and you care too much. You’re too liberal, you’re too conservative, and so they’re not getting regular people. Or—and this is the worst thing—they’re using pools of people who have agreed to be survey takers, which are not the least bit full of average people. They’re full of people who think a cool thing to do to make a little money on the side is to be a survey taker. So that’s why they’re not getting representative people. So, one, you’ve got to get to regular people, and you’ve got to give them the survey quickly, and give them lots of ways to take it. And one of the things we love, a couple methods we use are texts and emails. And if you get the text or email at 4:00, I don’t care if you don’t start responding until 9:00. I don’t care if you don’t finish responding by next morning. You’ve got a few days. So, you do it at your convenience, which is, I think, essentially important, and it feels more anonymous. So, the first way you start compensating is regular people. And the second way is you provide people as anonymous as possible ways to give the information. And whether that’s a text or an email, or an automated call, or a live caller who goes out of their way to make it clear how anonymous the poll is, or other digital methods that we’ve considered proprietary, we try to give people the comfort that this is anonymous, and that it’s a real poll, because that’s what they’re nervous about. “Is this real?” You know, “Am I on the other end of somebody who is going to put a list out of what people said?” So, we always give a way to link—anything that’s delivered digitally—all give a way to link to our website and Twitter site. “This is a real polling company, you can check us out.” We even have a line on there that says “This is a real poll, you don’t get a goofy prize to take it,” you know, “check us out.” So, we try to give people a sense that one, it’s real, two, we take your privacy seriously. We want your honest opinions. You know, we all know somebody that has that Facebook account that has the pictures they put with their children on it. It’s just proper and perfect, and you never say anything inappropriate. And then a lot of those people have another Facebook account that they kind of troll on. Well, the one they troll on is what their real opinions are, and that’s what I’m trying to get to. That’s the person I want to interview is the person that runs their troll account, not the one that runs their perfect little family picture Facebook account, because that’s what they really think. So, a lot of it is trying to get to them, and it’s not perfect because anytime somebody has to say, “I’m for x versus y candidate,” they are still running the risk that they’re telling that to somebody who may use it against them, and they’re scared. And add to that Republicans are four to one or five to one—depending upon the state—less likely to participate in a poll.

Jeff

Why is that?

Robert Cahaly

Because they don’t believe in them. They don’t know, again, why you’re asking. I mean, we have seen people have their opinions thrown at them. So, a lot of Republicans are antsy, you know, “Who are you?” “Why are you calling me?” “Are you really with a polling company?” “Am I going to be on a list?” “Am I going to be on some website tomorrow because I said I’m supporting Trump?” I mean I just ask people to use good logic. Get out of all the media spin and think about it. Do you know somebody who lives in a really fancy neighborhood who you know is for Trump? Do you think that person would be comfortable putting a yard sign on their yard in that neighborhood? And in most of America, the answer’s no. And do you think that person who maybe drives into a big city and parks their car will be comfortable having a Trump’s sticker on their car? And most of the time the answer’s no. And I’m saying, what do you think when they get a call from a live person on a Tuesday night that says, “Hello Miss Jamison. My name is Todd Jones, and we’re doing a political survey. Miss Jameson, are you for Biden or are you for Trump?” Do you think she’s going to say Trump? There’s no way she’s going to say Trump.

Jeff

Well, doesn’t that imply then that live calls will, because they have less perception of anonymity, that they become less effective if you’re trying to correct for social desirability bias?

Robert Cahaly

Yes. So, the sacred cow of the polling establishment is the sour meat, exactly. So, the thing you get an A for doing on the rating groups that lose elections is the thing that is actually the worst.

Listen to the full episode here to catch all of Cahaly’s insights, as well as other episodes of The Political Trade.