Greening the Music Festival Industry

Organizations like REVERB and Sustain Music & Nature are helping artists, fans and industry workers reduce the environmental impact of outdoor music

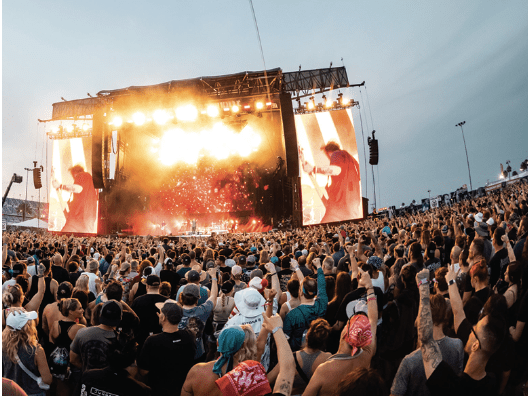

Thanks to a documentary film on the 1969 Woodstock Music and Art Fair in New York, generations of rockers know what a devastating effect an outdoor festival can have on the environment: mountains of garbage rising from a sea of mud.

The movie’s message didn’t fall on deaf ears. Today, organizations are working to improve safety, security, cleanup and even sustainability at outdoor music venues and events. They’re still far from perfect, though. According to Dogan Gursoy, one of the editors of the book Festival and Event Tourism Impacts, as much as 80% of festival waste is not sorted for recycling.

Since 2000, Gursoy, a professor at Washington State University, has studied how mega events reshape communities and alter the environment. With truckloads of trash and a lack of recycling, major festivals can even change the land itself, he said.

In 2019, for example, Lollapalooza concert promoters were charged $645,133 to repair the damage the four-day festival inflicted on the grounds of Chicago’s Grant Park. That year, a rainstorm sent nearly 400,000 festival-goers stampeding through the grass, bushes and mud. It was the highest price tag for a Lollapalooza cleanup since 2011 and involved installing sod, spreading mulch and planting shrubs.

Damaged landscaping costs festival heads a lot of dough, but it doesn’t pose nearly as big of a problem as trash, Gursoy said. Fortunately, help is on the way.

REVERB

Organizations like REVERB are paving the way for sustainability and environmentalism in the music industry, says Chris Spinato, REVERB’s manager of communications.

“It’s really about reducing the environmental footprint of music and being more sustainable and then engaging as many people as possible to take action,” Spinato said.

The nonprofit organization was born in 2004 when environmentalist Lauren Sullivan and her husband Adam Gardner of the band Guster had become sick of feeling bad about the environmental impact of touring and decided to take action.

Eighteen years later, REVERB has “greened” more than 350 tours and has supported around 4,800 other nonprofits focused on environmentalism, sustainability, climate change and social justice.

The organization also works with artists, venues, festivals and fans to spread their message through campaigns that include #RockNRefill, which provides concert goers with an alternative to single-use water bottles. There’s also REVERB’s Kitchen, farm programs for fresh produce and outreach to artists’ causes.

According to Spinato, only 5% to 12% of plastic is recycled in the U.S., so while recycling initiatives are great, it’s better to reduce the amount of plastic used. Through REVERB campaigns—and local vendors—more festivals and venues are ditching plastic drinkware and utensils for reusables, aluminum cans and compostable materials.

“Climate change, environmental problems—these are huge issues,” Spinato said. “It’s not something that any single person can solve, but we have a responsibility to take action. If a single person brings a reusable water bottle to a show versus using plastic, it’s a small action. But imagine multiplying that across a whole tour.”

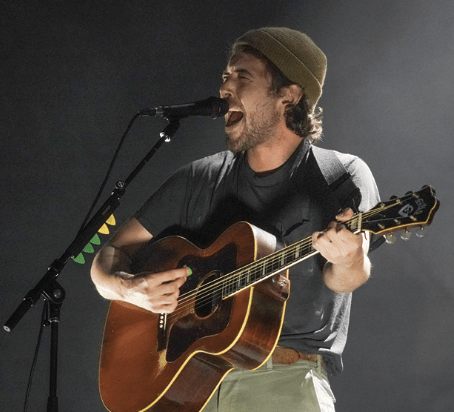

Recently, REVERB has worked with touring artists such as Dead & Company, Billie Eilish, Harry Styles, The Lumineers, Lorde and the Dave Matthews Band. The result is different each time, but the mission is always the same: educate and empower fans while creating easy ways to get involved.

For example, at the Dave Matthews Band’s Warm Up tour, fans can stop at an Eco-Village to refill on free water at the #RockNRefill stations, learn more about the Music Climate Revolution, get involved in DMB’s commitment to plant 1 million trees for their third year in a row, and register to vote.

Spinato says REVERB looks at sustainability in the industry holistically: trash, single-use plastics, energy consumption and transportation. Activists often focus on one aspect of the problem, such as single-use plastics, but more issues need to be addressed. The idea is to reduce more than produce, whether it’s trash, greenhouse gases or carbon emissions.

“The word is getting out that there is something we can do,” Spinato says. “We can make the music industry more sustainable. Sustainability is no longer just an optional, nice thing to do. It’s a must.”

That’s a daunting task, but REVERB isn’t alone. Other groups are joining the effort.

Sustain Music & Nature

Nonprofits like Sustain Music & Nature are using music to involve fans in the conservation of public lands.

In 2015, the husband-and-wife team of musician Harrison Goodale and environmentalist Betsy Mortensen found a way to combine their two passions: music and conservation. They developed Sustain Music & Nature to combat the doom-and-gloom messaging they were hearing.

“It’s hard to know how to get involved,” Goodale said. “When you’re faced with an existential crisis, it’s a lot easier to ignore it. We want to capitalize on the cultural capital that musicians have to really bring people together. It’s about taking a celebratory approach that involves getting outside.”

Sustain Music & Nature has launched two initiatives: Songscapes and Trail Sessions. In both, the organization works with officials who administer public lands across the U.S. to bring together music and nature to become one.

In Songscapes, the nonprofit sends artists to songwriting retreats on public lands. The musicians stay for four to seven days, learn about the area and conservation efforts, and then write a song inspired by the experience.

The goal is to turn the musicians into advocates for conserving and convince them to use the emotional hook of music to influence the public.

Trail Sessions take a similar approach with people who aren’t musicians. In parks throughout Colorado, New York and New England, the sessions take people on guided educational hikes that end with an intimate acoustic performance by local musicians.

“Music has been a great way to bring folks together for a cause,” Goodale said.

But nobody says it’s easy.

Spinato noted that people often find it difficult to confront and acknowledge their own environmental footprint, the first step toward making progress.

“The best way to deal with these concerns that we have is to take action,” Spinato said. “Don’t put it all on a single moment. What’s more impactful is that you start taking actions in your everyday life or joining groups that are doing really good work in your local community.”