Wrestling With Reality

Spontaneous or scripted? The pros sometimes improvise on a predetermined storyline to create a crowd-pleasing spectacle.

Redneck soap opera. Populist performance art. Repressed homoerotic fantasy. Whatever it’s called, professional wrestling is nothing if not compelling. The characters are myriad, the spectacle is grand and the drama is fierce. Whether fans believe it’s 100% true (it’s not) or 100% fake (it’s not that, either), there’s no debating the broad appeal of an entertainment odyssey that rakes in hundreds of millions of dollars every year.

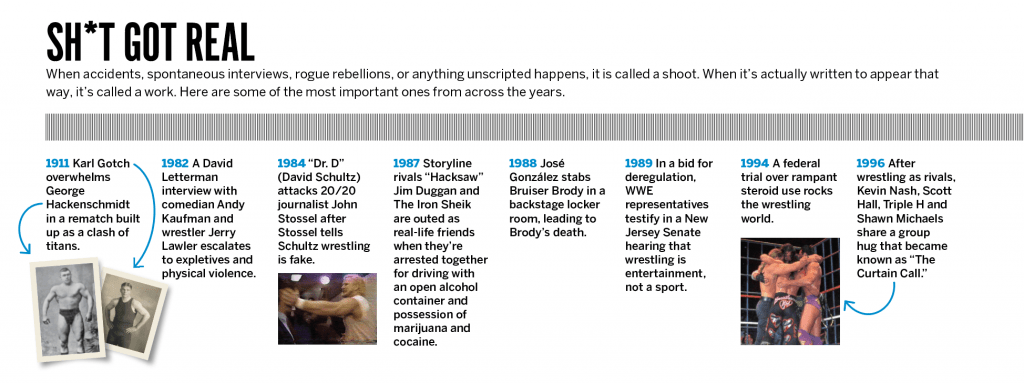

Wrestling’s relationship with reality has always been as fluid as the high-flying luchadors, Mexican pro wrestlers known for aerial maneuvers and garish facemasks. The inner workings were revealed as far back as the early 1900s, when Karl Gotch dominated George Hackenschmidt in a rematch. Their second bout bore little resemblance to their original two-hour bout. Gotch, exploiting his opponent’s knee injury, broke kayfabe (slang for what’s supposed to be real) to defeat Hackenschmidt in 30 minutes. The record-setting crowd of 30,000 was not pleased.

For the next century or so, interest in the sport waxed and waned, mostly through small regional organizations. The inevitable mergers occurred, and by the ‘80s two major players survived: Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling (WCW) and Vince McMahon’s World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE), which was formerly called the World Wrestling Federation (WWF).

The illusion of truth took a major hit in a 1989 New Jersey Senate hearing, when legislators, in an effort to avoid regulation, described wrestling as “entertainment … rather than … a bona fide athletic contest.” That made fakery official and began a transformation that eventually pushed wrestlers to dress as mummies, brandish supposedly poisonous snakes, bury their rivals alive and rise from the dead with the help of a lightning bolt.

With such a brazen demand for suspension of disbelief, what was left to be real?

The skills

The physical training required for pro wrestling can be brutal. Wrestlers have to develop the strength to toss around a usually cooperative but still massive opponent. They learn enough acrobatics to bounce around the ring like crazed gymnasts. They absorb blows and take falls that would challenge even a Hollywood stunt double.

Acting talent pays off. To advance the storyline of a match, wrestlers may fake an injury or stoically mask the pain of a wound that’s real. They can take hold of the microphone and hold forth in mock interviews, lending an air of reality to their latest rivalry.

Wrestlers have to become masters of improvisation. Even when the outcome of a match is predetermined, no one necessarily maps out a plan to get there. It takes inventiveness to discover ways to keep the plot alive.

The drama sometimes rises to the level of spectacle. Wrestlers learn to make big entrances and exits, sparking and holding the interest of enormous crowds. Their characters take on the characteristics and proportions of comic book super heroes and villains, complete with alter egos that mutate as their careers evolve.

The injuries

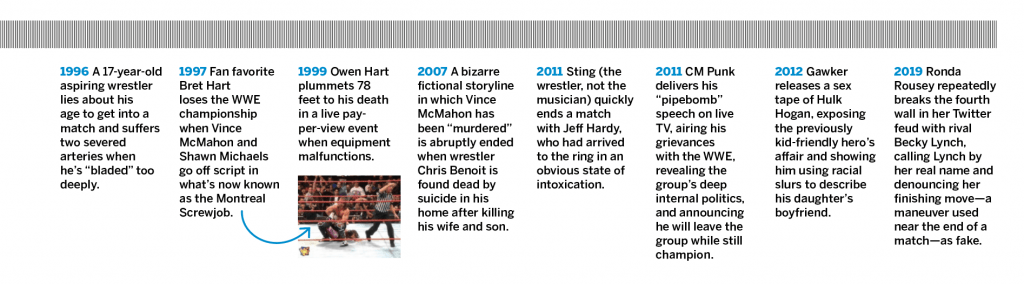

Everyone expects wrestlers to keep finding new ways to push physical boundaries, and that makes injury all but inevitable. Wrestlers power through pain because the show is live and must go on. The abuse ranges from the freakish to the tragic.

Vince McMahon, for example, tore both his quads during a benign ring entrance. Mick Foley, who once finished a match after having his ear ripped off, went home from 1998’s Hell in a Cell with a concussion, a dislocated jaw, a bruised kidney, a hole in his mouth, a body full of thumbtack punctures and two missing teeth. Owen Hart wasn’t so lucky—a stunt malfunction claimed his life in 1999.

It’s little wonder so many wrestlers fall into drug abuse and early death.

The money

The WWE has grown into a market behemoth through advantageous acquisitions, ruthless employment strategy and savvy media deals. It bought and phased out its two largest competitors, World Championship Wrestling (WCW) and Extreme Championship Wrestling. Its stock skyrocketed nearly 400% after it renegotiated broadcast rights with Comcast and Fox in April of 2018.

Although WWE has been a juggernaut for decades, change is beginning to take hold. In the last few months, attendance has been slipping and stock prices have been falling. A new organization, All Elite Wrestling (AEW), has been founded by Tony Khan, son of billionaire Shahid Khan, and has been challenging WWE for television ratings.

Part of the problem for WWE comes down to labor disputes. WWE wrestlers, in violation of federal law, work as independent contractors. They are expected to buy their own insurance (Lloyd’s of London stopped insuring them in 2017) and to provide their own transportation between cities. Fans have begun to view the WWE as predatory because of its cavalier treatment of its stars.

Meanwhile, the AEW seems to be more in touch with the people who buy the tickets. Although it hasn’t adopted a formal policy, the AEW has begun creating full-time employment status, with benefits, for some of its top-tier wrestlers. If it continues along that path, sentiment toward the AEW will only grow more positive. That could translate into some real change in the market.

The Very Real Chinlock

In spring 1985, when the World Wrestling Federation hype machine was making the media rounds for the debut of its new WrestleMania, a difference of opinion between wrestler Hulk Hogan and actor and media personality Richard Belzer took a very real and nearly disastrous turn on live television.

Hogan appeared on a talk show called Hot Properties. It was hosted by Richard Belzer, who later became known for his role on Law and Order: SVU. During the interview with Hogan, Belzer stopped short of calling wrestling “fake,” but suggested the matches weren’t unduly dangerous.

During a physical demonstration, Hogan put Belzer in a front chinlock, cutting off circulation to his head. Belzer passed out and when Hogan let go, Belzer’s head hit the floor and a pool of blood started to form. Belzer was hospitalized and received stitches. He sued Hogan for $5 million and settled out of court.

Bobby Shepherd, creative director for tastytrade, considers himself a bourbon, banjo and body slam enthusiast.