Vinyl’s Revival: A Decade of Growth

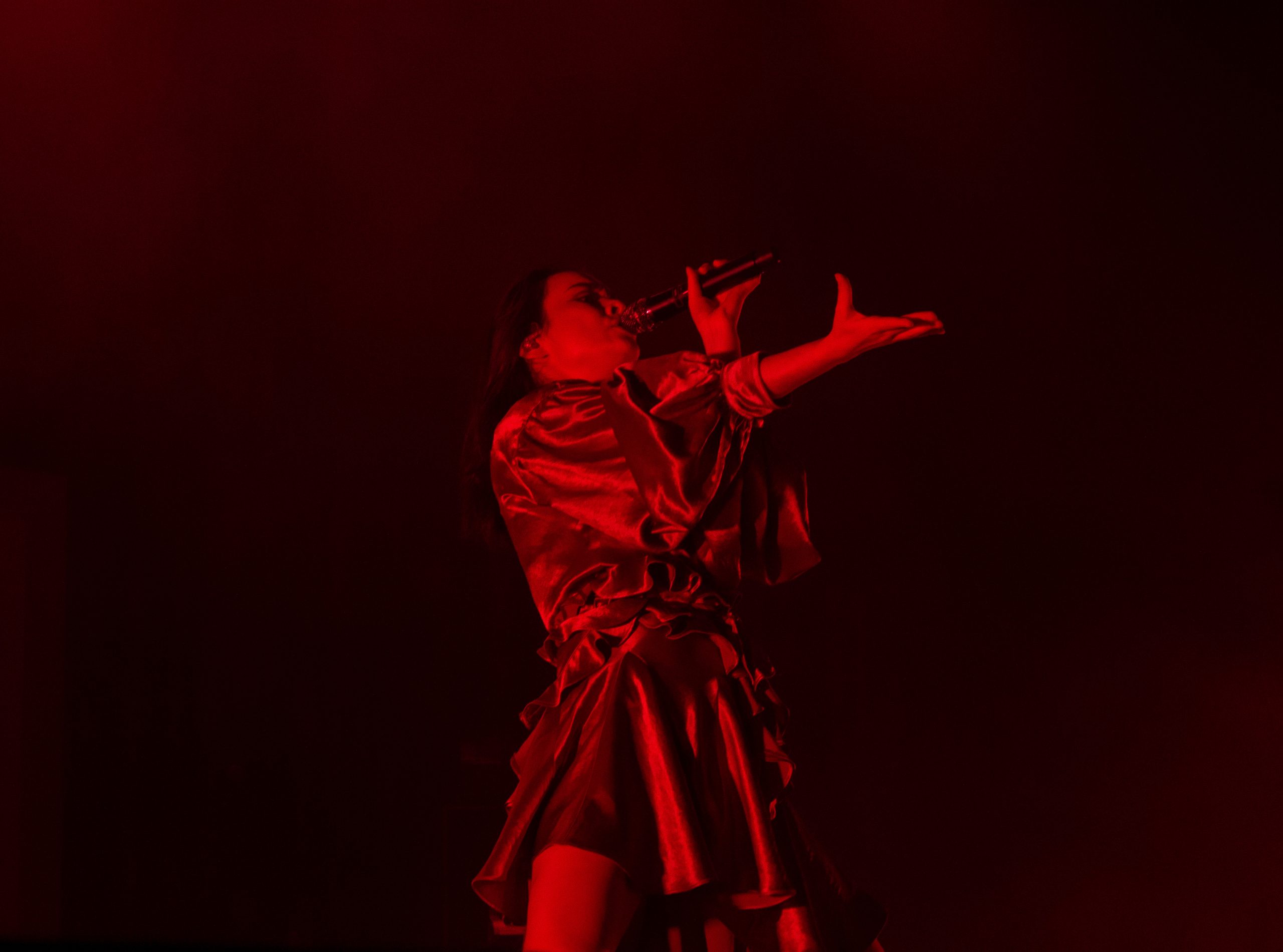

A seemingly endless amount of music is just a smartphone tap away, but that isn’t stopping a growing demographic of music-lovers from listening the old-fashioned way: laying some vinyl down on a turntable

What do vinyl records and craft beer have in common?

“Nothing” may be the instinctive response, but Rick Wojcik, owner of what Rolling Stone deemed the country’s third-best record store in 2010, says the two share more similarities than one might think.

“Vinyl follows the beer business,” Wojcik told Luckbox. “In the early 20th century, Chicago had a bunch of local brewers. They didn’t call themselves craft brewers, but they were guys who did a good job. It was the same thing with vinyl pressing plants.”

Both endured steep declines as the century wore on. The United States had 857 breweries in 1941, and that number shrank each consecutive year until 1978, when it hit its lowest point since prohibition at only 89 breweries, according to Brewers Association data. The number of breweries would stay under 1,000 until 1996.

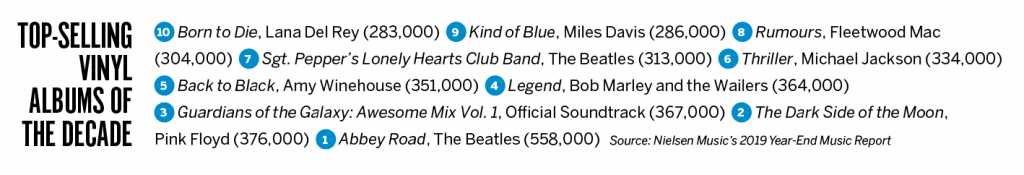

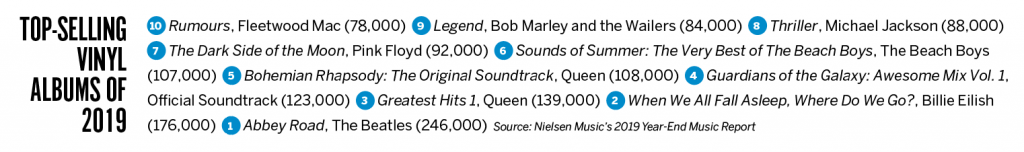

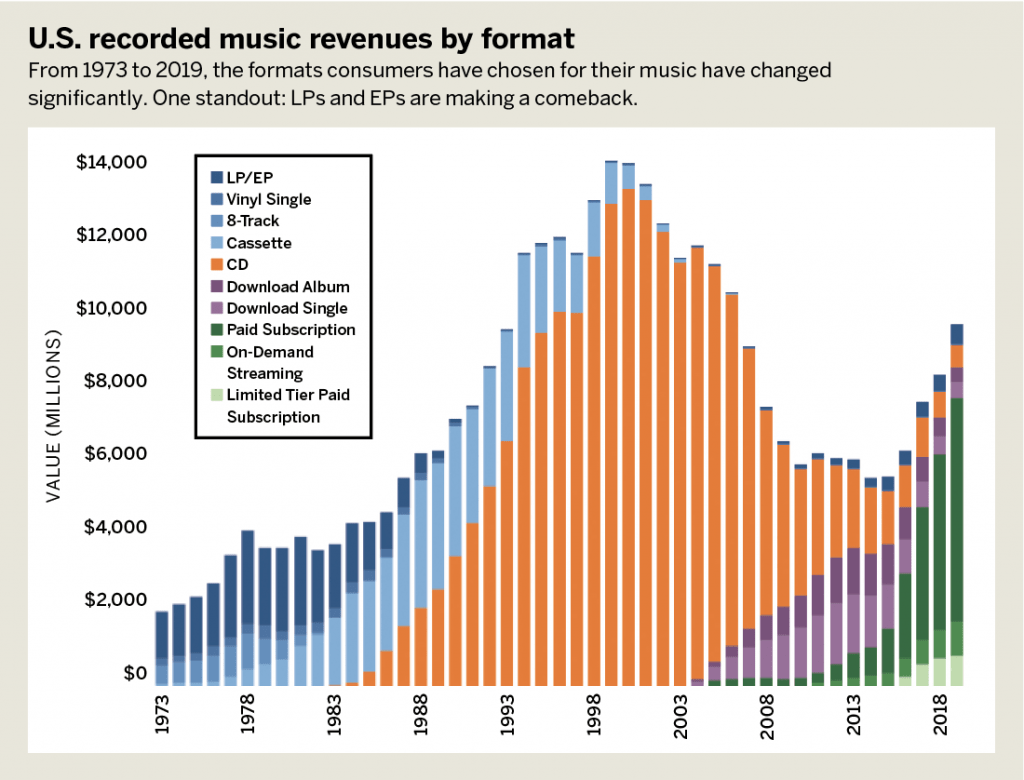

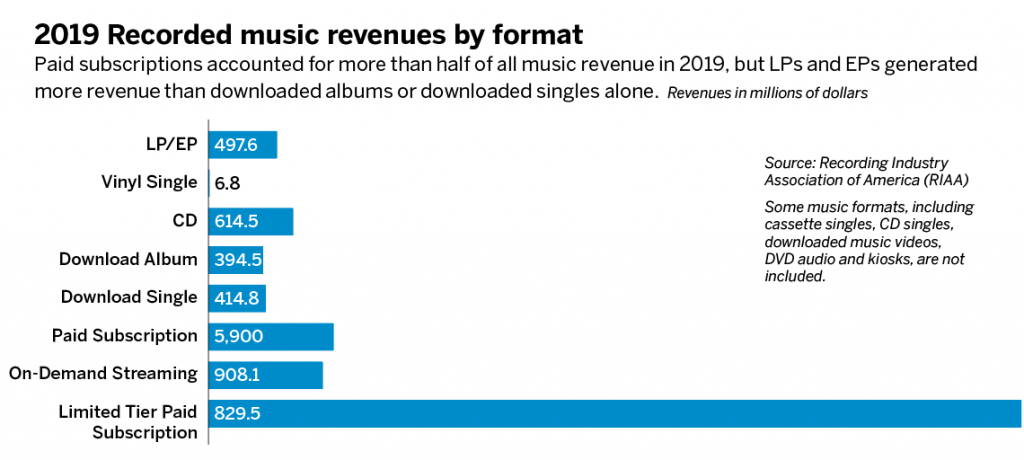

Sales volume for LPs and EPs decreased every year from 1981 to 1993. In 1980, vinyl accounted for close to half of all recorded music sales—making it by far the most-popular medium at the time. But in 2000 it scored only 0.2% of sales, left in the dust by the then-dominant CD, according to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).

Still, it doesn’t take a keen eye to pick up on the surging popularity of microbreweries and vinyl records in recent years. Grocery store beer aisles have been allocating more space to craft brews—in some cases designating entire sections for them. Meanwhile, it’s increasingly commonplace to find records for sale in bookstores and department stores across the country.

Sales numbers affirm the anecdotal observations. Overall U.S. beer sales by volume were down 2% in 2019, but craft brewer sales volume was up 4%, now accounting for 13.6% of the U.S. beer market by volume. The number of U.S. breweries is larger now than ever before, at 8,386 in 2019, according to the Brewers Association.

In the same year, LP and EP sales volume hit 19.1 million units, an increase of 14.6% over 2018, according to the RIAA. What at its lowest points made up a mere 0.1% of all recorded music revenue now accounts for 4.5%.

Craft beer aside, what’s powering the vinyl revival? With seemingly infinite libraries of on-demand music just a cell phone tap away, thanks to subscription services and streaming, why would anyone go out of the way to use a turntable?

Vinyl enthusiasts may point to the novelty of large album artwork, the innate collectability of records or the warm, beloved crackle that can be heard when playing them, but Wojcik chalks it up to something simpler.

“People are willing to pay for quality,” he said, adding that the quality of vinyl has long been on the rise. “It’s just stunning. The effort that’s gone into the cover art, the production, the cardboard—better than even a record from the ‘60s—and that’s a real tribute to the quality these guys are bringing to it.”

And if anyone should know about the trends of the industry, it’s Wojcik.

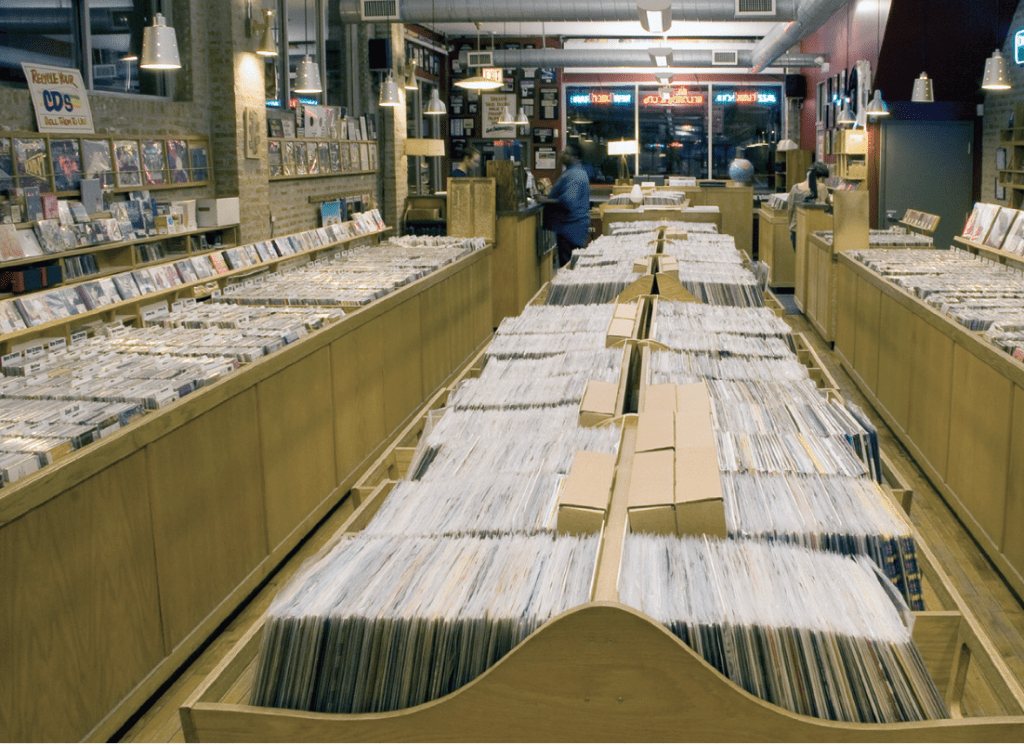

He’s been working in the music business since the late ‘80s, when sales volume for the LP and EP formats underwent some of their steepest declines. He had experience under his belt as a DJ and a part-time record store worker before co-founding his own record store, Dusty Groove, with JP Schauer in 1996.

Dusty Groove started as an online-only part-time hobby but became a full-time operation in only four months. By the end of 2001, it had an in-person retail presence open seven days a week in Chicago’s Wicker Park neighborhood.

In addition to being named the third best record store in the country by Rolling Stone, the store’s been recognized by The Wall Street Journal, Time and Reader’s Digest. It was also the subject of the 2019 documentary Dusty Groove: The Sound of Transition.

“One of the things people would say to me 20 years ago was, ‘Aren’t you afraid? It’s all digital music—nobody pays for anything,’ ” Wojcik said. “And I would say, ‘Look, radio has sucked for a long time. I love digital music because this is how all these kids are getting turned on to music. When they find something they love, they’ll be willing to spend money on it.’ And the years have proven us right.”

Young people, including high school students stopping by the store after school, make up one of Dusty Groove’s largest emerging customer demographics in the last five years, Wojcik said. The store makes roughly $3 million in gross sales a year.

Wojcik attributes the store’s survival and growth to its ability to attract customers from all over the world and from all age groups, races and musical interests. Customers buying jazz feel just as comfortable in the store as someone buying hip hop, he said. And despite its principal reputation as a record store, Dusty Groove offers a wide selection of CDs, representing half of its business.

“We sell more jazz than anything else,” Wojcik said. “Second is probably soul music, and third is rock, and we didn’t even sell much rock music until about a decade ago, when people just kept saying, ‘Please, we need to sell these records and there’s not a lot of record stores left around.’ ”

An integral part of the business is buying used records from customers looking to part with their collections, make some extra money—and space—or liquidate a relative’s estate. With 31% of Americans willing to pay for music on vinyl, according to a 2019 YouGov survey, one pressing question is “What makes a record valuable?”

“Condition is No. 1,” Wojcik said. “No. 2 is something that’s really unfamiliar to you.”

Customers are quick to mention their Beatles and Elvis records, he noted, but the often-overlooked, more-obscure albums are the ones most likely to fetch higher resale prices.

With the vinyl revival apparently in full swing, one can’t help but wonder if now’s the time to start building a collection in hopes of one day selling it for a profit. Wojcik said people even try to come up with algorithms for investing in records. “That’s the worst idea I’ve ever heard of,” he adds.

Instead, he offered this parting advice: “If you follow your taste and invest in something you love, you’ll enjoy it while you have it. That’s always the best art investment.”