Making a Buck in the Band

Music streaming gives artists exposure but not much else

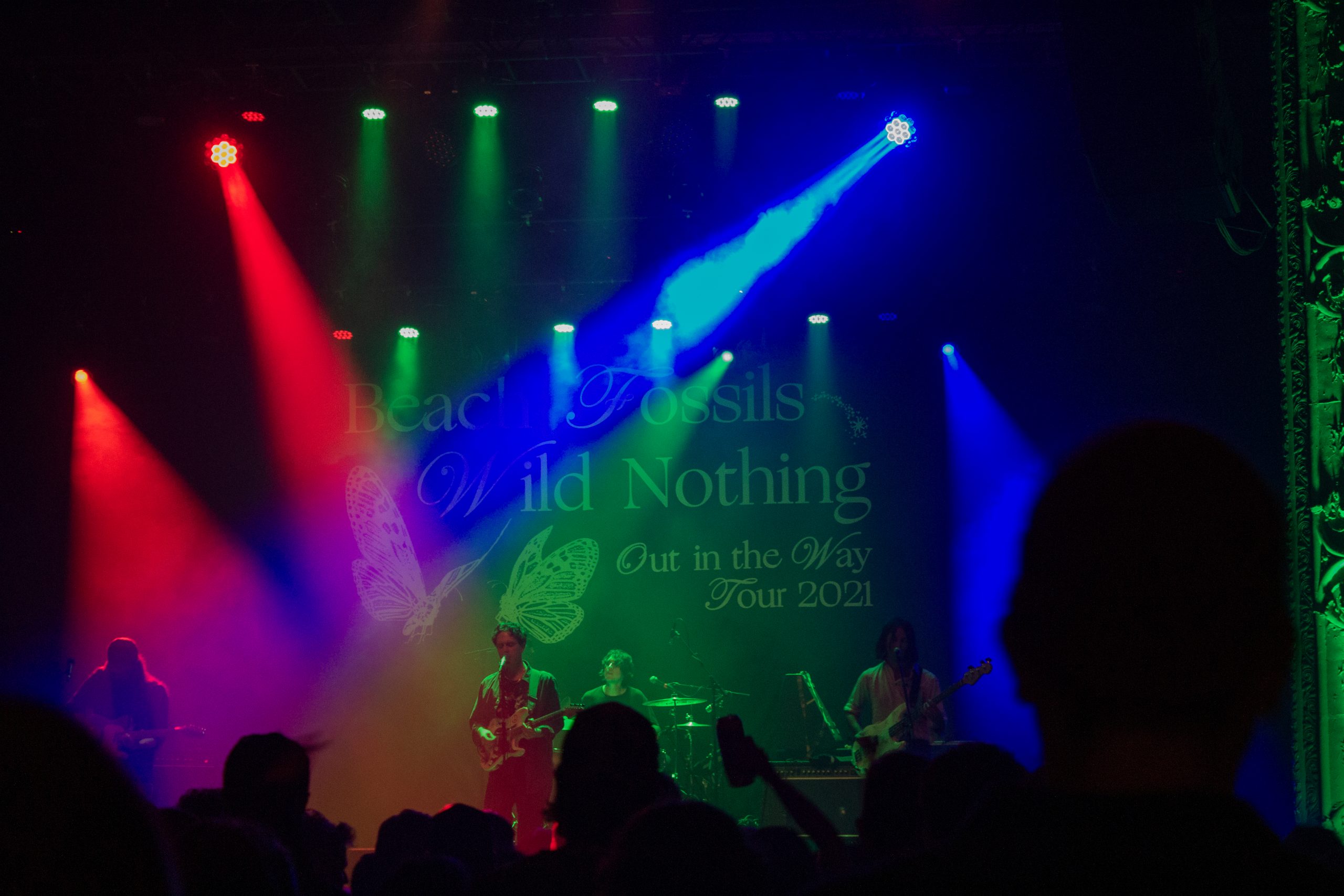

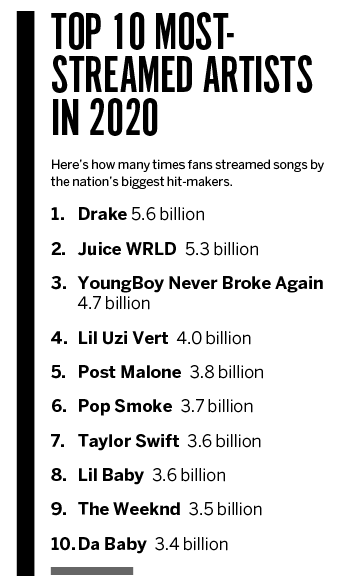

Music streaming gives relatively unknown artists a bigger microphone but a smaller paycheck. The mic’s larger in the sense that musicians reach a sizeable audience more quickly than ever before, but the resulting royalties won’t cover the bills unless a performer is approaching the popularity of Taylor Swift, Amazon Music’s Top Artist for 2020.

Those trends matter because the pandemic has given streaming services a boost as fans seek music to fill their lonely hours of isolation. Before COVID-19, platforms like Amazon Music, Spotify and Apple Music were already gaining market share at the expense of radio and live shows, and now they’re more quickly crowding out older ways of listening.

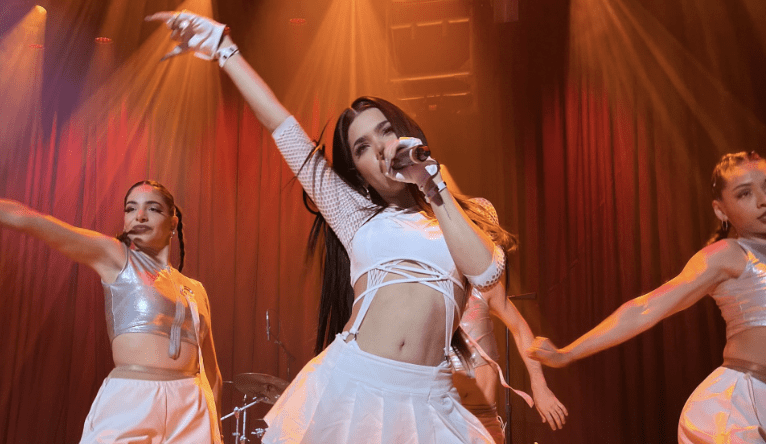

But is the convenience of listening to the latest Dua Lipa track with the simple tap of a finger worth making up-and-coming musicians struggle to make ends meet?

“There’s no reason you should be working day shifts at McDonald’s if your band is raking in 100 million streams a week,” said Nick Bilski, a Chicago musician in the band SŌK. To stay afloat, he works at Guitar Center and teaches music lessons.

“The losers are the 99% of artists who aren’t at Beyoncé’s level of fame,” said Ben Sisario in a New York Times article. “And they’re angry about not sharing in the music industry’s success.”

But streaming has its advantages for some denizens of the music business.

Platforms profit

Streaming services generate 83% of global music industry revenue and provide something the industry never had before: regular monthly revenue, Sisario said in The Times article. “To oversimplify, the big winners are the streaming services and the large record companies,” he noted.

And the winners have a mountain of cash to divvy up. Streaming revenue in the United States amounted to $10.1 billion, according to the Recording Industry Association of America.

Streaming services “pay out roughly 60% to 70% of their annual revenue to ‘rightsholders,’ a group that includes musicians, record labels, songwriters, publishers—anyone who has a financial stake in the sales of a given record,” according to a Pitchfork article.

But at least artists have an easier time getting their music onto digital distribution platforms like DistroKid, cdbaby, tunecore, Record Union and Reverb Nation than they did in the days of having to convince a record label to release their songs. Musicians choose which streaming distributor they want based on benefits and features.

Vivian McConnell, a Chicago musician who goes by the stage name of V.V. Lightbody, has been on streaming platforms for the past 10 years. Today, listeners can find her recordings on Amazon Music, Spotify, Apple Music, Pandora Premium, Deezer and TIDAL, but the money is not what keeps the lights on. She would prefer not to think about how often she’s streamed but feels she has to pay attention to the numbers because that’s how a majority of listeners now consume music.

Some of the singles McConnell has on streaming services were released through a record label that collects a large percentage of the streaming royalties. She released others independently, and their royalties come directly to her. Combined, her nine singles not associated with a record label have been streamed 90,000 times since 2018, earning her $455 (60% of streaming royalties).

The payout to artists

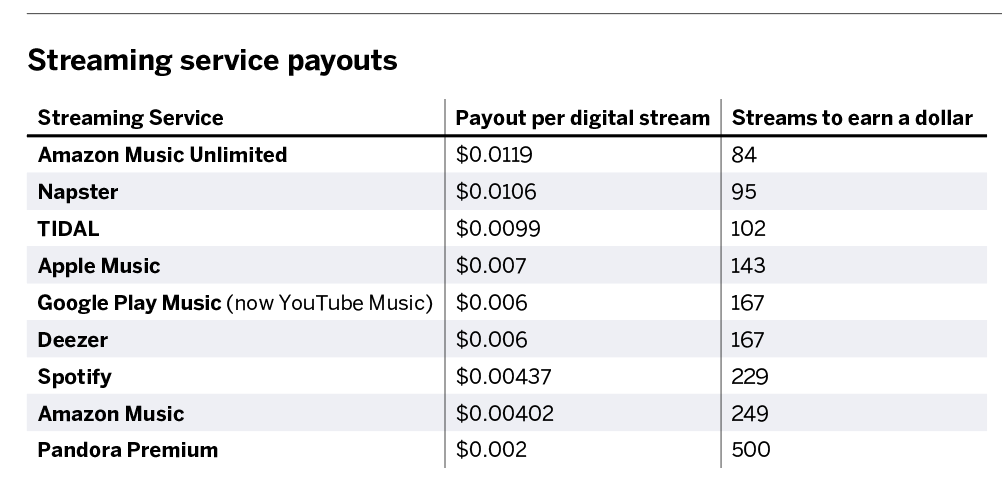

Every streaming service offers a slightly different payout. In “Streaming service payouts,” below, there are nine platforms in order of how much they pay artists per digital stream, and how many streams it takes to earn a dollar.

A song might need a minimum of 250 plays to make $1. One track reaching 10,000 plays on Spotify equals roughly $40 in streaming royalties.

“At an average payout of $0.006 per song stream, a musician living in the United States needs three million plays annually to have a gross income of $12,000,” according to a Hypebot article. And the number of streams required to make a buck gets larger when members of a band divide the royalties.

On the brighter side, streaming tends to pay royalties directly to artists. When musicians relied on sales of CDs, vinyl or cassettes, the profit was larger but split up among as many as 10 different types of contributors. Key players in the making of a CD, for example, include the artist (6%), producer (3%), songwriters (4%), distributor (22%), manufacturer (5%), retailer (30%) and record label (30%).

Suppose a band with four members who write their own songs was selling CDs for $16 and receiving a royalty rate of 11%, thus clearing $1.76. The producer would take 3% of that, leaving the band $1.71. Distribution would then cost 43 cents, leaving the band with $1.28. So, each of the four band members would get 32 cents.

That’s why it takes around 1,500 song streams to make as much money as selling one album.

Artists fight back

In self-defense, artists sometimes hire attorneys to track compensation, said Christopher Johnson, assistant director of education for an organization called Lawyers for the Creative Arts. His clients often feel they aren’t fairly compensated, so he does the math to ensure their number of streams matches the royalties they receive. But with platforms like Spotify mostly relying on subscriptions to fill their pool of royalties—and with people either listening for free or paying $4.99-$9.99 a month—there isn’t much money for royalties.

“The most successful artists are the ones who are able to find every little niche market for their stuff, whether it’s in film, TV, etc.,” Johnson said.

Collective bargaining and protests can help, too. McConnell belongs to the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers’ (UMAW) Chicago chapter, which campaigns for larger payments from streaming platforms. She recently took part in a demonstration outside Chicago’s Spotify headquarters to demand the company pay its artists a penny per stream.

Some musicians found a reason for hope in April when Apple Music announced its intention to begin paying artists one cent per stream. “As the discussion about streaming royalties continues, we believe it is important to share our values,” Apple said in a letter. “We believe in paying every creator the same rate—that a play has value and that creators should never have to pay for featuring.”

No other streaming platform has made that promise, and money alone won’t solve all of the problems musicians have with streaming.

“It is a really awesome tool for discovering new music, but [as an artist] you have to be actively pushing yourself out of the algorithm,” McConnell said. “Smaller artists are being overlooked. If people are using streaming apps, they really need to know that it doesn’t support artists at all.”

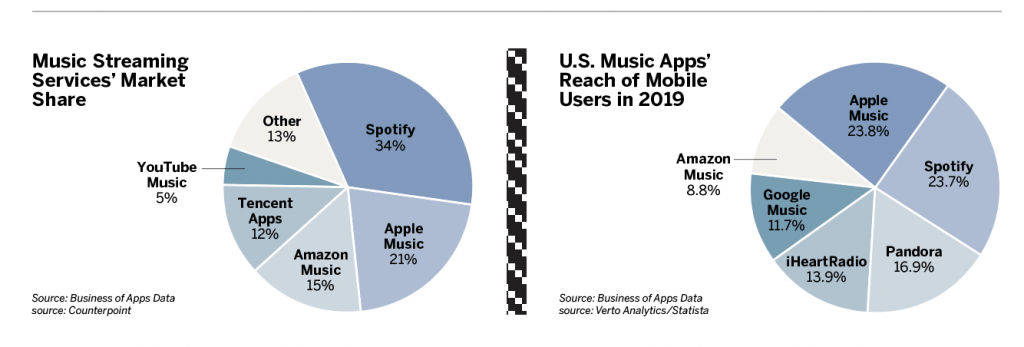

But the failure to nurture performers isn’t stopping the apps from growing. At the end of Q2 2020, Spotify’s 155 million paying subscribers gave it a 34% market share, Apple Music’s 72 million subscribers were good for a 21% share and Amazon Music had 55 million subscribers for a 15% share. Every year, Amazon Music increases its market share, and its Amazon Music Unlimited subscription pays artists more than its competitors unless Apple lives up to its penny promise.

While platforms are competing for market share, artists are fretting about compensation. Determining who collects royalty checks often raises issues, especially when a band with several members is involved, according to Daliah Saper, a trademark, copyright and media attorney in Chicago.

Music royalties are always confusing, and the confusion increases with digital streaming because of the multitude of ways to split music and the differences in platforms’ payouts, Saper noted. “Artists have to be educated and they have to understand all of the different ways they can exploit their music. Artists get into these collaborations and then they’re confused as to why they’re getting a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of that stream.”

Getting noticed

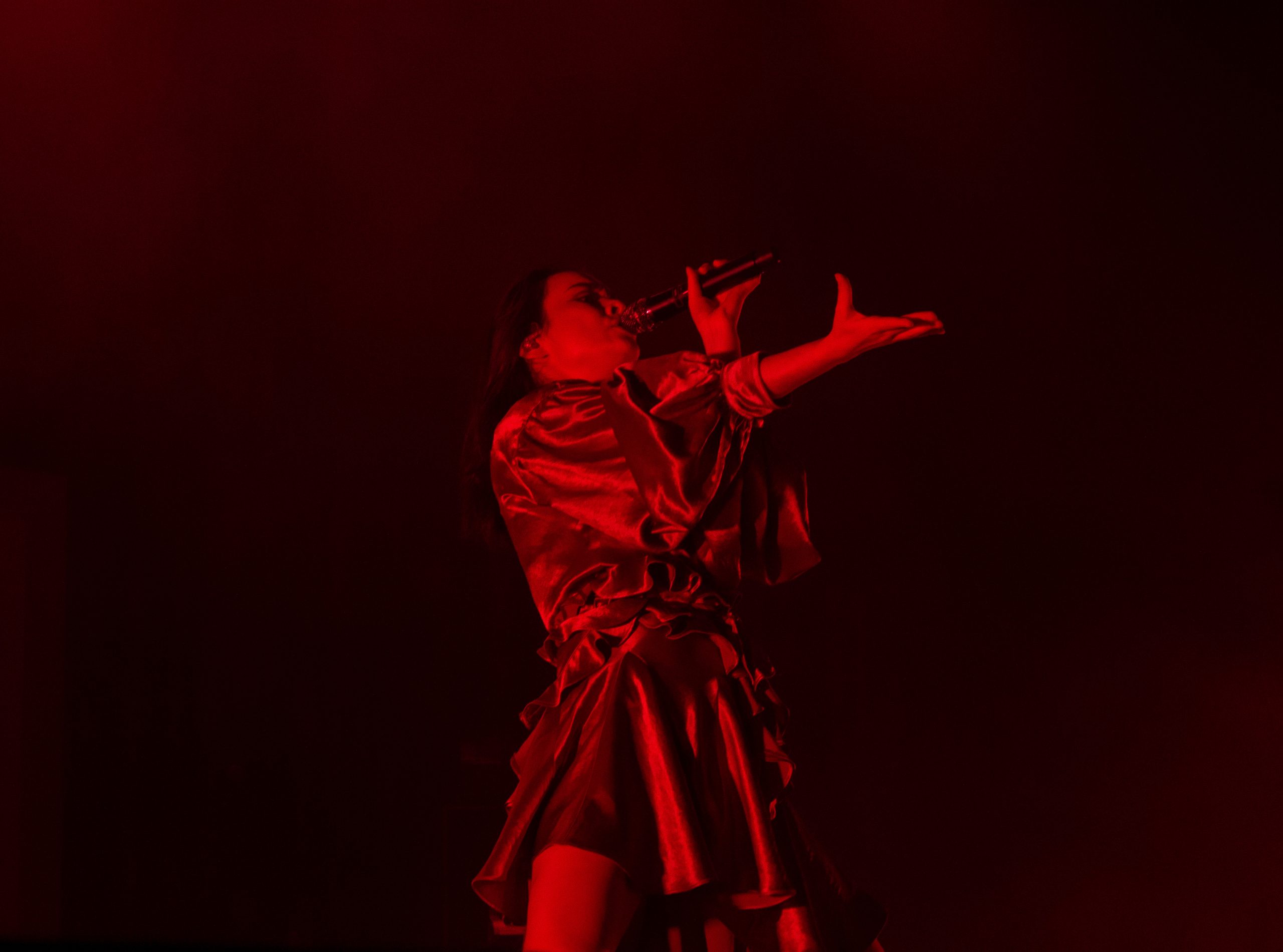

Even though a majority of artists are not making much money from digital downloads or streaming, they can still use them to promote themselves.

In one example, Diego Martinez, a Brooklyn-based musician known as Di Ivories, uses platforms to his advantage. He leans on Spotify to build a fanbase and make it onto playlists but goes to Bandcamp and Amazon to sell merchandise and make slightly more money. Most of his income as an artist comes from merchandise sales, he said.

It’s up to artists to do the work and not just wait for the streams to come in, Martinez said. He wants to see his number of streams grow but wants to see that growth turn into monetary value.

To make money and grow as artists, musicians have to become players in every sector of the music industry, Martinez said. That means planning single releases so they make it onto curated playlists, promoting themselves frequently through social media, devoting time to creating and selling solid merchandise, playing live shows whenever possible and strategizing every move to ensure it will provide benefits in the long run.

In the short run, Martinez monetizes his music by registering with Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI), an organization that collects royalties for songwriters and publishers when anyone uses their music commercially.

“It’s more important for artists to find their own way,” Martinez said. “If not, then they’re just a starving artist. In reality, we all are.”