Inflation, Hot Air & Wind

Hype and ballooning both rely on hot air and some wind at your back. But in the case of ballooning, not too much wind.

In each issue of Luckbox, the editors and contributors bring an array of perspectives to a single theme. This time, the focus on hype got us thinking about hot air, and that somehow led to the idea of hot air ballooning.

With a national ballooning event approaching, it seemed like the right time to emblazon the Luckbox logo on something larger than a T-shirt. So, we set out for Phoenix to achieve a more elevated perspective on ballooning. Some might call it a “balloondoggle,” but we viewed it as “research.”

That’s how Luckbox came to sponsor a balloon in the Hare & Hound race at the Arizona Balloon Classic this past January. A crowd of 20,000 turned out to see 25 balloons—or aerostats, as they’re sometimes called—compete in the 11th annual outing.

Unfortunately, officials canceled the race a few minutes before liftoff because high winds threatened to hinder navigation and could make landing dangerous. Our dream of hot air turned out to be exactly that.

“-If you actually need to get somewhere, a hot air balloon is a fairly impractical vehicle. You can’t really steer it, -and it only travels as fast as the wind blows. But if you simply want to enjoy the experience of flying, there’s nothing quite like it. Many people describe flying in a hot air ballo-on as one of the most serene, enjoyable activities they’ve ever experienced.” —How Stuff Works

1783 Pilatre de Rozier, a French scientist, launches the first hot air balloon. The passengers—a sheep,

a duck and a rooster—stay aloft for 15 minutes before crashing.

1783 Two French brothers, Joseph and Etienne Montgolfier, pilot the first flight of a hot air balloon with people aboard. They stay up for 20 minutes.

1785 Pilatre de Rozier foregoes the farm animals and attempts to cross the English Channel using a hydrogen-enhanced balloon. The balloon explodes an hour after takeoff, making him the sport’s first fatality.

1914 Throughout WW1, both sides use balloons for military reconnaissance.

1960 In a ballooning breakthrough, Ed Yost develops a balloon that carries its own lightweight burners and bottled propane. Longer flights and better maneuverability ensue, giving birth to the modern era of ballooning. Yost flies for a record-breaking

95 minutes.

1987 Richard Branson and Per Lindstrand are the first to cross the Atlantic in a hot air balloon, flying 2,900 miles in 33 hours.

1991 Branson and Lindstrand are first to cross the Pacific, traveling 6,700 miles in 47 hours with a top speed of 245 mph.

2002 On his sixth attempt, Steve Fossett completes the first solo flight around the world, covering 22,100 miles in 13 days.

Dark Side of Balloon

Before social media gave birth to Twitter wars, duelists used swords or pistols to settle arguments over reputation, love and principle. Perhaps the most flamboyant of all duels was conducted aloft in 1808.

Mademoiselle Tirevit, a celebrated dancer, was in a love triangle. Her suitors, apparently believing they had “elevated minds,” agreed to a winner-take-mademoiselle duel to the death in hot air balloons over Paris. They took turns shooting at each other with blunderbusses loaded by seconds who doubled as pilots.

Here’s a contemporary report of the outcome:

“When they had mounted to the height of about 900 yards, M. Le Pique fired his piece ineffectually; almost immediately after the fire was returned by M. Granpree, and penetrated his adversary’s balloon; the consequence of which was its rapid descent, and M. Lee Pique and his second were both dashed to pieces on a house-top, over which the balloon fell.”

—Duel in Hot Air Balloon, Northampton Mercury, 1808

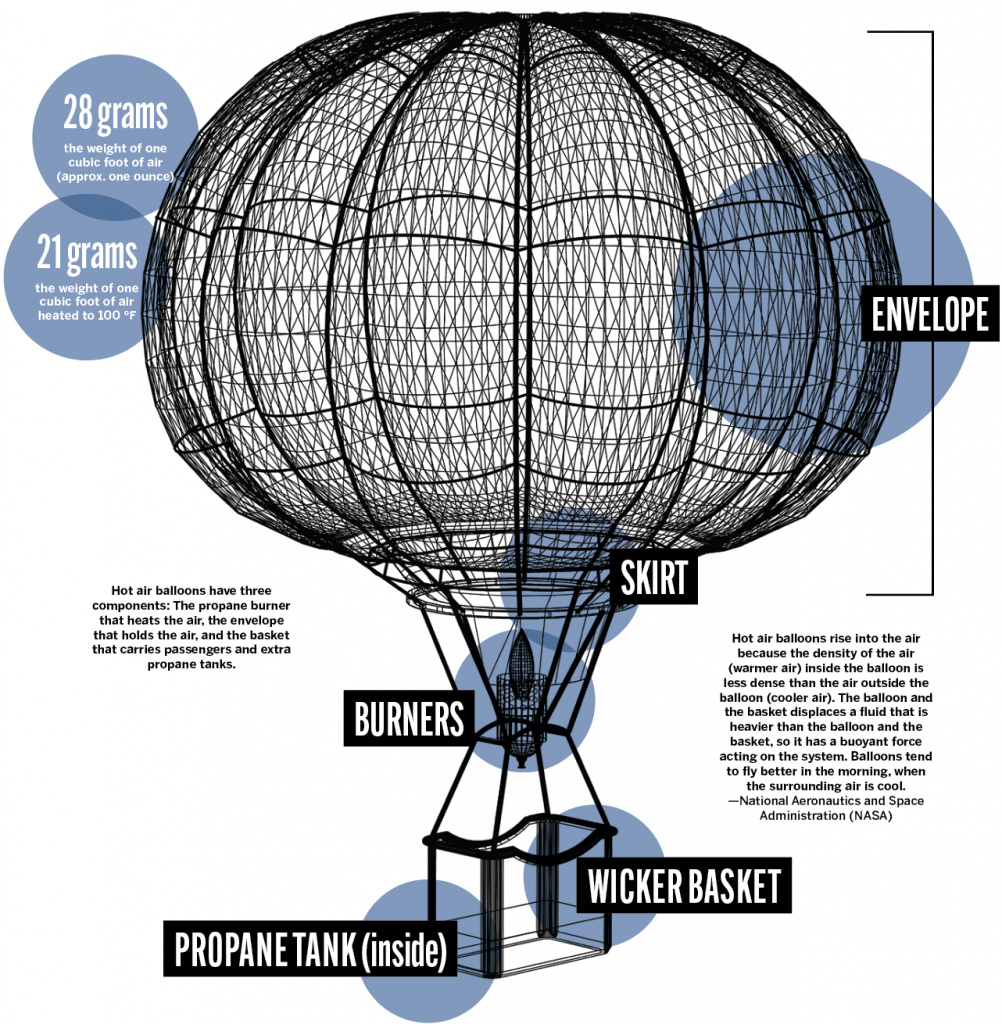

Hot air is literally lighter than air. The physics behind hot air ballooning relies upon the Archimedes Principle which states that the buoyant force on a submerged object is equal to the weight of the fluid that the object displaces. So, each cubic foot of air in a hot air balloon can lift about 7 grams (or ¼ of an ounce). That’s why hot air balloons need to be so large—the envelope must contain a large enough volume of heated (lower-density) air in order to generate sufficient upward buoyant force to lift the weight of its passengers.