Do Prediction Markets Mitigate Cognitive Biases?

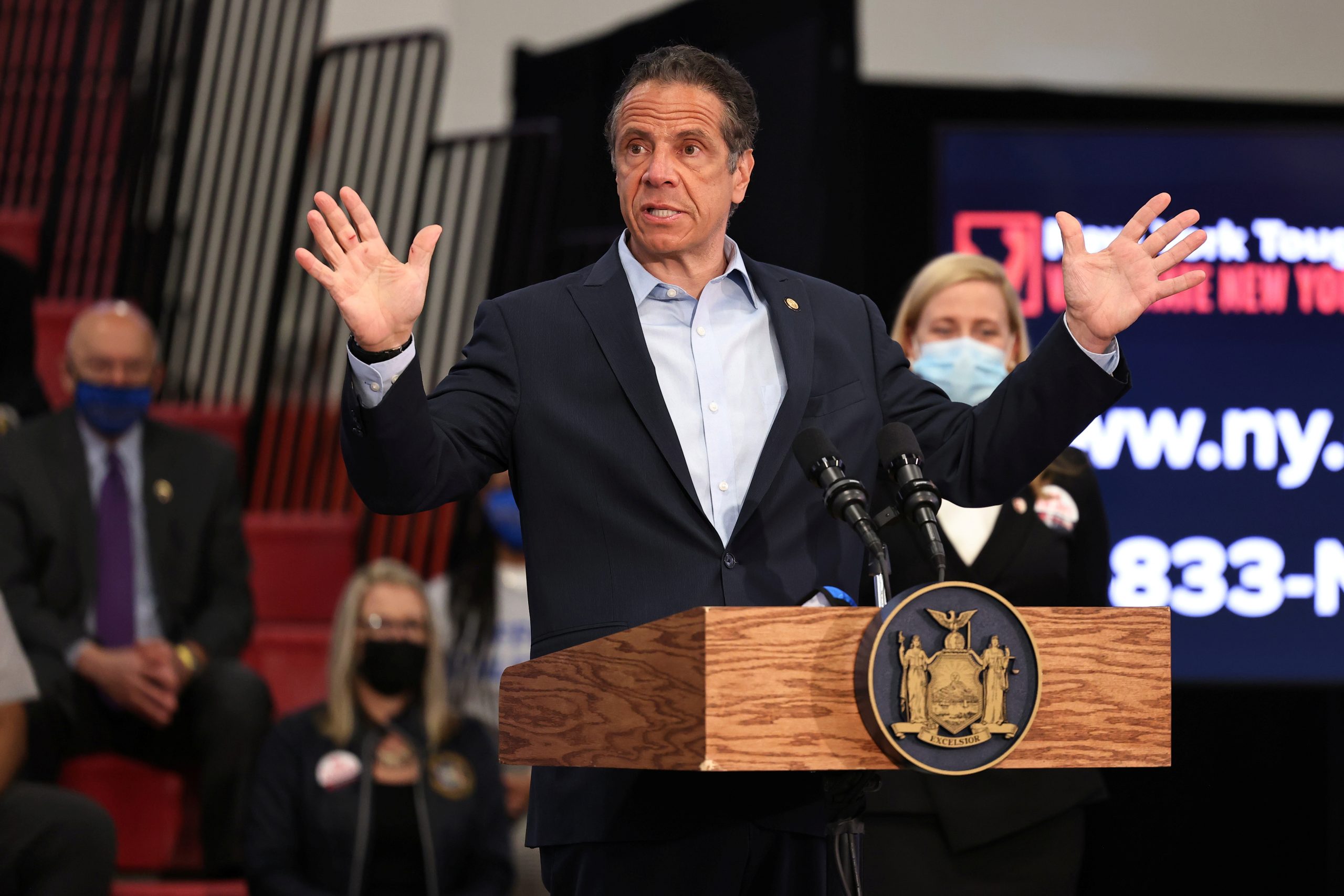

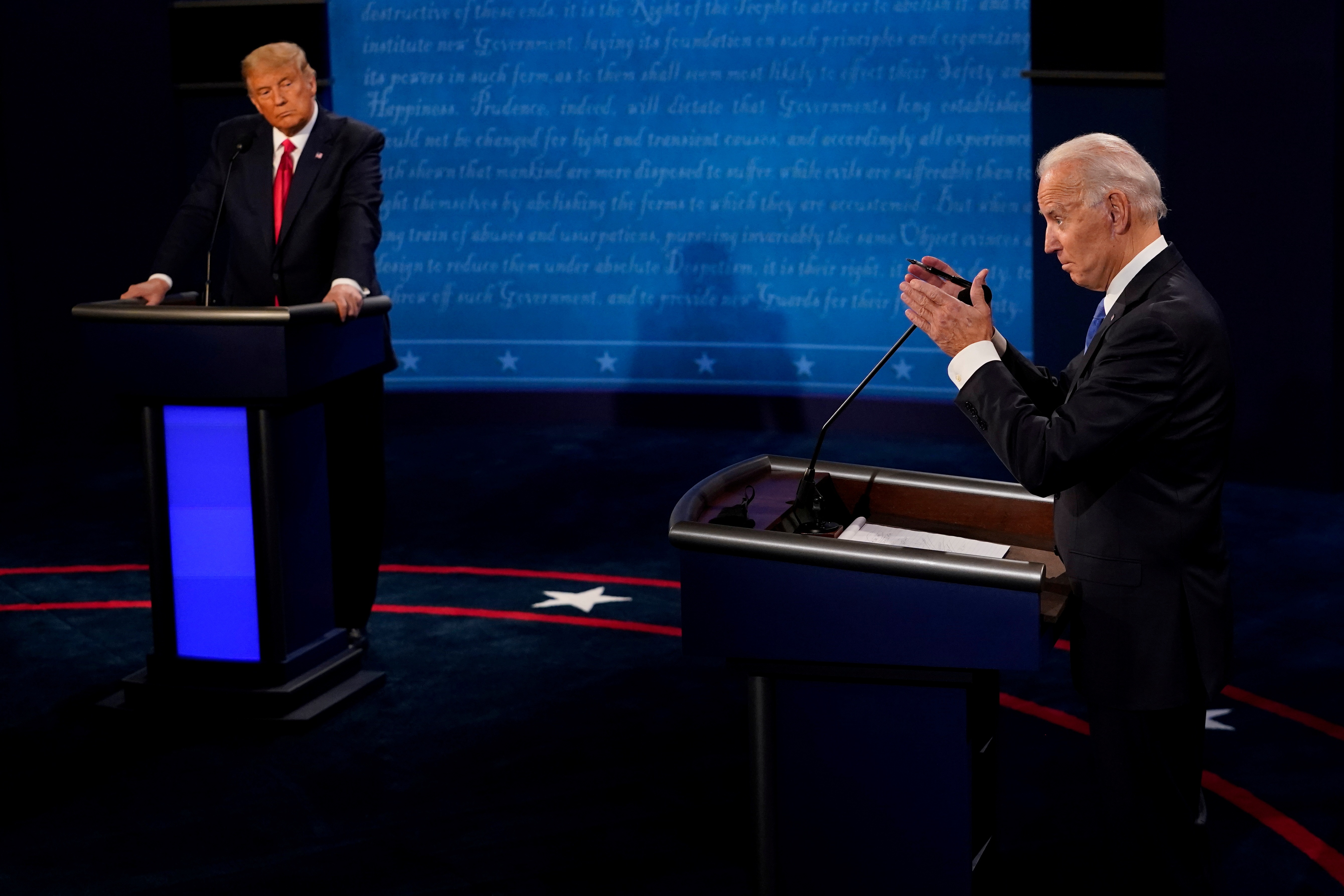

Prediction markets' real-money stakes might combat motivated reasoning. To illustrate, how would you bet on Pete Hegseth's confirmation outcome?

During the past several years, Luckbox has advocated for the legalization of prediction market wagering on political outcomes. Aside from our bias toward democratized access to free markets, we maintain that prediction market platforms can help us learn to process information more effectively and make better investment decisions. They teach us to recognize our cognitive biases—and what could be a better training mechanism than political biases?

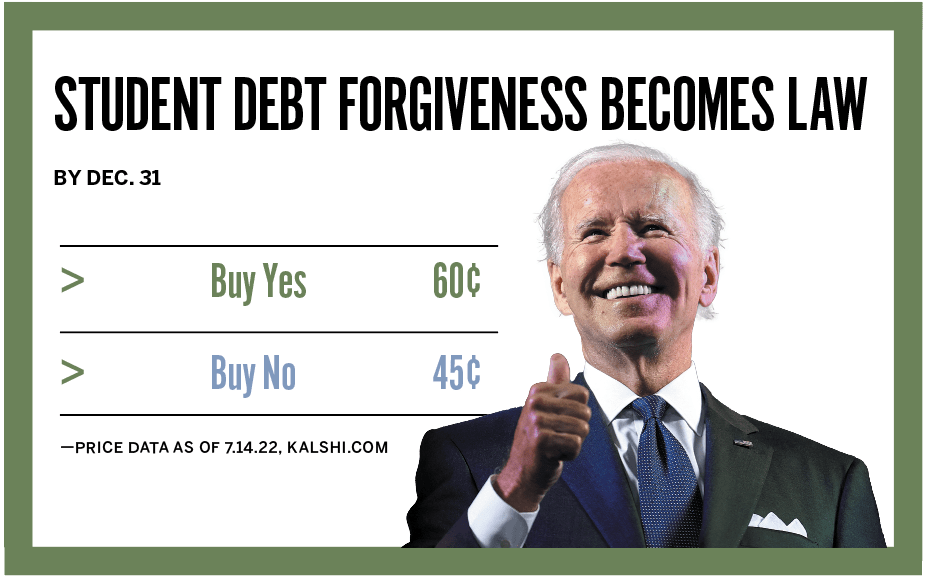

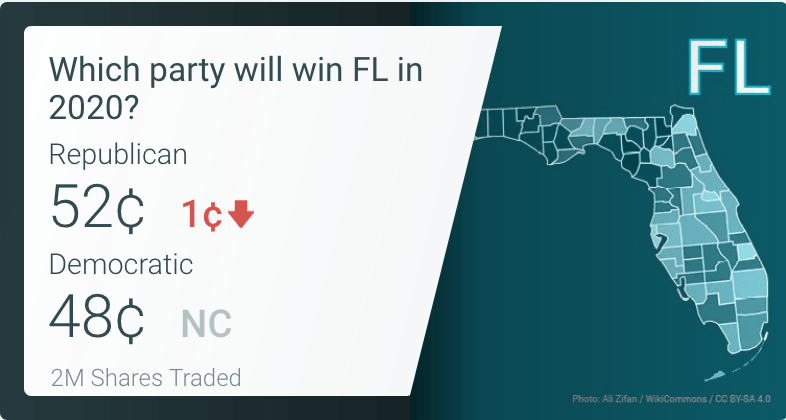

To illustrate, let’s look at the question on the minds of many this week: Will Pete Hegseth be confirmed as Trump’s Secretary of Defense? He’s among the most controversial nominees picked by a controversial president-elect, so his grueling confirmation hearing came as no surprise. Nevertheless, the prediction markets seem rather certain of confirmation. As of this morning, Kalshi puts that probability at 96%, while Polymarket pegs it at 95%. Is that overly optimistic? The Republicans will enjoy a 53-47 majority in the Senate, so it’s not that much of a leap to expect partisanship to assure Hegseth’s confirmation.

But our esteemed forecasting panel, along with our wise Luckbox readers, put the probability of a Hegseth confirmation lower, at 50% and 59%, respectively. It’s not surprising because the nation is politically divided down the middle. The half that favors Trump are inclined to expect (or hope) his nominations will be confirmed. The other half that opposes Trump is likewise biased to ignore the relevant Senate math and project failure for Trump’s nominees. The prediction markets seem to process the relevant data more rationally. That begs the question of whether prediction markets correct for cognitive biases.

The argument favoring the utility of prediction markets suggests the financial commitment of putting your money where your (head, heart or mouth) leads you can help mitigate the cognitive biases that can impair forecasting. Anyone can jawbone their political opinion, but it’s another thing to back it up with cash on the line. And it’s the money on the line (so the argument goes) that effectively lessens instances of the cognitive bias known as “motivated reasoning,” where people tend to predict outcomes in sync with their preferences and aligned with their partisan identities.

Motivated reasoning breeds overconfidence in favorable outcomes for one’s “side” and dismissal of contrary evidence. It results in “selective information processing,” where we readily accept information that confirms our views while subjecting contradictory information to much greater scrutiny.

In the instance of the Hegseth confirmation question, selective information processing would cause those with ideological biases against Donald Trump (and his Cabinet nominees) to grant greater weight to stories challenging the nominees’ qualifications than the incontrovertible, yet simple math of the Senate.

In fact, there’s also something called “asymmetric scrutiny,” which means it takes especially strong evidence to convince us to accept conclusions that don’t jibe with our beliefs. The threshold for “good evidence” is higher if the thesis the evidence supports doesn’t fit our views.

For those that think they have an information advantage because they are so well-read on such issues—not so fast.

Research has shown that motivated reasoning can actually increase with greater political knowledge and cognitive sophistication, as people become better at crafting counterarguments and justifying their preferred positions. This suggests that simply being “smarter” or more informed doesn’t necessarily protect against this bias.

Taber and Lodge’s 2006 study “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs” published in the American Journal of Political Science showed politically knowledgeable participants were more likely to counter-argue against information that challenged their beliefs.

The concept of “sophistication-interaction theory” developed by Robert Luskin and others also suggests political sophistication can amplify biased processing instead of reducing it.

As prediction markets like Kalshi and Polymarket continue to expand their inventory of “markets,” such as Fed moves, inflation, economic releases, asset prices, etc., savvy active investors should add these platforms to their watchlists and consider their prevailing sentiments to be a rational resource for market data, research and sentiment.

So, let’s see where the conclusion of Hegseth’s fiery confirmation process leaves us. Perhaps we’ll learn something about our own biases.

Jeff Joseph is Luckbox editorial director.