The Murky Future of Political Futures Markets

A prediction market insider asks regulators for leniency in the battle over wagering on political outcomes.

The sometimes sleepy world of political prediction markets has found itself, rather suddenly, in a straight-up frenzy.

In August, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) revoked PredictIt’s no-action relief and ordered it to shut down by February over alleged but unspecified failure to comply with the conditions of its 2014 exemption.

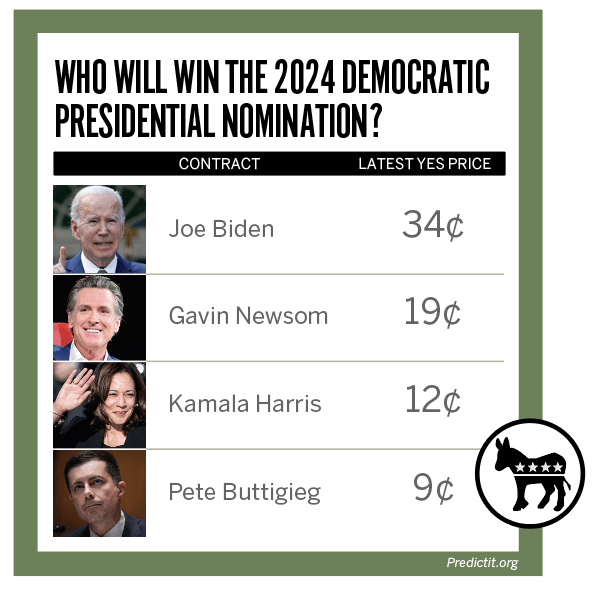

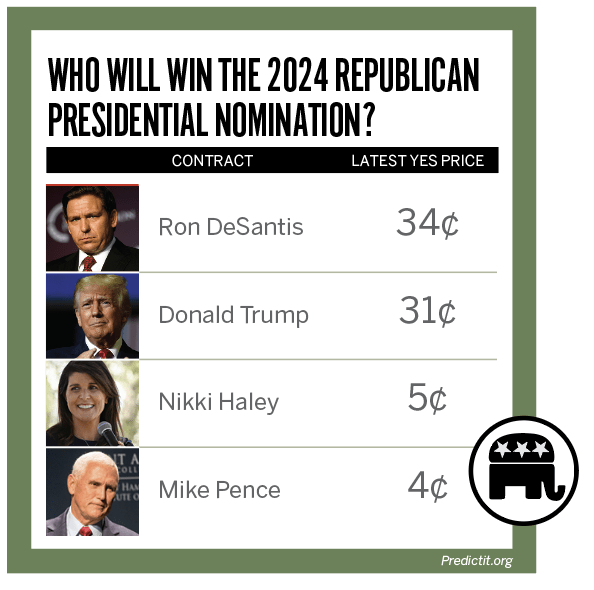

It will let the popular political prediction platform’s 2022 midterm markets play out, but the even larger 2024 presidential markets (with over $10 million in open interest) will have to be unwound. Somehow.

It remains to be seen whether this marks the untimely end of a worthy experiment or the point when a fledgling asset class ascends into the pantheon of fully regulated products. Either way, this cottage industry’s future is in the hands of federal policymakers whose inscrutability is these markets’ own stock in trade.

To understand where we are now, an abridged history of prediction markets is in order.

1992: The University of Iowa’s Tippie College of Business asks the CFTC to allow it to operate small-scale, real-money markets on presidential and congressional election outcomes. The CFTC granted no-action relief to the “Iowa Electronic Markets” (IEM), meaning it would allow them to operate with impunity (and without submitting to the typical oversight of futures exchange) within the narrow confines of the research-focused project.

1999: Ireland-based Intrade is founded. The trading platform offered binary contracts on various events but became best known for its markets on U.S. elections. While it never acquired regulated status or no-action relief in the U.S., regulators were relatively hands-off with Intrade over the next decade.

By 2012, however, Intrade was a borderline household name, with a large and predominantly U.S.-based user base and widespread major media coverage as a favorite barometer of the Barack Obama-Mitt Romney presidential race.

Regulators went from hands-off to gloves-off.

Weeks after the election, the CFTC sued Intrade for listing unregulated futures products. The company closed its U.S. customers’ accounts, and within months had stopped trading altogether, against a backdrop of allegedly misappropriated client funds and the death of its founder atop Mt. Everest.

Only months earlier, the regulated futures exchange Nadex had formally applied to list election outcomes on its platform. The CFTC replied with a swift and hearty hell no. The colorful late Commissioner Bart Chilton blasted the idea of “political poker,” which he feared would turn regulated markets into “some entertainment gambling orgy endeavor.”

2014: Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, is granted no-action relief by the CFTC to operate a market similar in structure and purpose to IEM’s.

Just in time for Obama’s second midterm elections, the overtly U.S.-focused PredictIt (at predictit.org) was born.

With operational support from Washington, D.C.-based Aristotle Inc. (including yours truly, under contract as a market curator until 2019), PredictIt went on to list many thousands of political contracts tied to election outcomes, legislation, regulation, court decisions, executive orders, opinion polling and even President Donald Trump’s Twitter tempo.

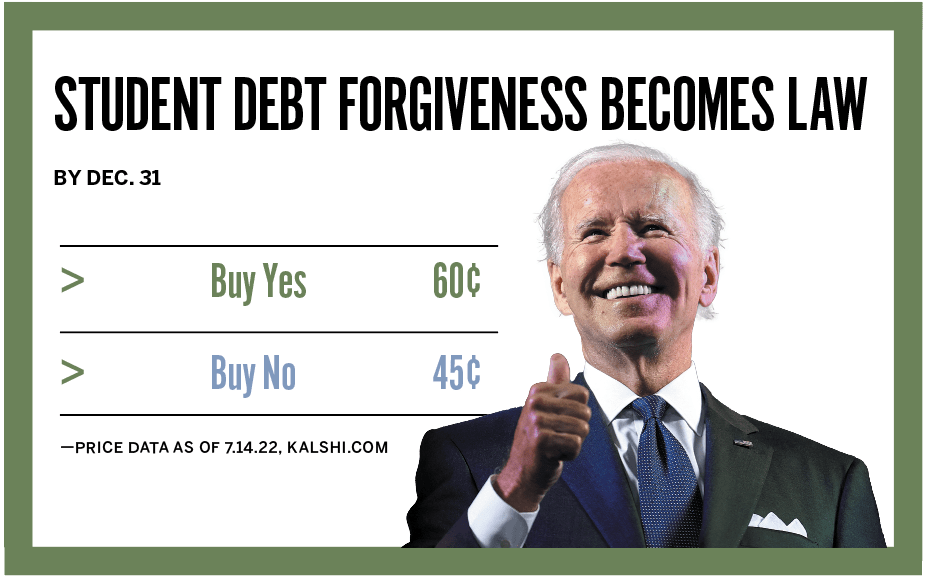

Last but not least, in 2021, the world met Kalshi. The prediction market freshman stormed onto campus waving something none of the upperclassmen had: full CFTC approval as a designated contract market. It was the first DCM organized specifically to list “event futures” (in theory, a sprawling superset of the sort of markets offered by Intrade, PredictIt, Polymarket, IEM and others).

Wielding the DCM superpower of self-certification—wherein an exchange may deem its own novel products in compliance with federal law and CFTC rules, putting the burden on the regulators to rule otherwise—Kalshi went to work.

It listed all kinds of wild and wooly products never seen on regulated markets in this country: Whether and when COVID dining restrictions would be lifted; whose album would be most downloaded this week and how many passengers TSA would screen today.

And while Kalshi wasn’t listing markets tied to election outcomes (by now manifestly the third rail of U.S.-regulated futures markets), it did wade into several of the political arenas where PredictIt had been making markets for years, including judicial confirmations, passage of legislation and approval polling.

Little by little, more operators were offering more products to more market participants. For once, an industry perpetually hamstrung by regulatory obstinance seemed to be making slow but steady strides toward a future of not quite unfettered innovation but at least less arbitrary obstruction.

CFTC flips the game board

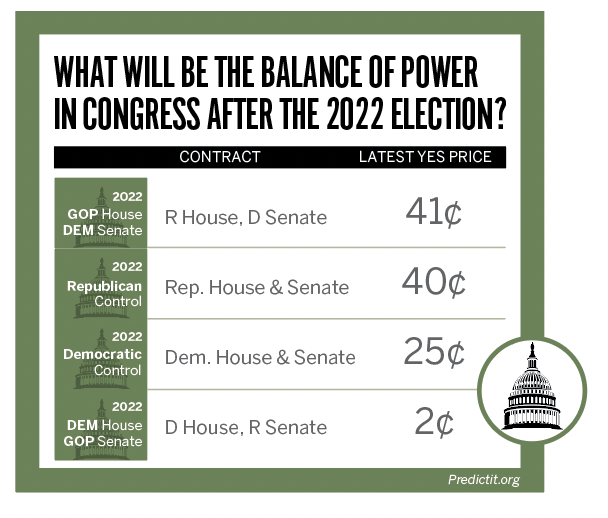

Only a few days after the CFTC announcement that it was revoking Predictit’s no-action relief, government filings showed Kalshi had recently applied to list markets tied to the outcome of the 2022 midterms, specifically which party would win control of each house of Congress.

That prompted the CFTC to undertake a statutory review, scheduled to conclude just days before the election, during which it has invited the public to comment on whether and how these contracts differ from those they rejected a decade ago when Nadex sought to list them.

Meanwhile, PredictIt and Aristotle have filed a federal suit against the CFTC, asking the court to reverse the “arbitrary, capricious” revocation of permission to operate its markets.

The decisions by both the CFTC (whether to allow elections on regulated exchanges) and the court (whether to overrule the CFTC and allow PredictIt to continue to operate its unregulated market), will determine whether this fledgling asset class will be relegated to its 20th century status, a plaything of European punters and VPN-wielding scofflaws. Or, on the contrary, whether it will be made a full-fledged citizen of American financial regulatory society.

While the request for public comment encompasses some 17 questions, the CFTC has three main areas of concern, as briefly dispatched below via excerpts from my own public comment in support of the markets’ approval.

1. Is this gaming?

In its 2012 rejection of Nadex’s proposed election contracts, the CFTC relied on a definition of gaming that includes any outcome of “a contest of others.” But this aggressive interpretation plainly does not reflect the Commission’s own criteria.

If a political campaign, in which multiple candidates vie for the “prize” of election to public office, qualifies under this definition, surely contests such as the Oscars, Emmys and Grammys (in which candidates vie for literal prizes) likewise qualify. Yet Kalshi has previously self-certified and listed numerous contracts tied to these contests without objection by the CFTC.

As for whether the CFTC should let the potential existence of state-regulated casino offerings tied to elections dictate that they are indeed gaming products, federal law grants the CFTC exclusive and preemptive jurisdiction over futures transactions. The Commission should resist any temptation to cede its explicit federal jurisdiction to state law or regulations.

2. Do these markets serve an economic purpose?

The CFTC wonders whether electoral outcomes have sufficiently meaningful or quantifiable economic effects as to be plausible hedging tools.

It is true that economic actors large and small (taxpayers, small-business owners, global corporations, households, shareholding retirees and healthcare patients) are in many cases predictably exposed to various election outcomes. Their efforts to measure and (albeit without reliable tools) manage their economic exposure to those outcomes is so evident as to have become cliche.

The top 50 interest groups had by June of this year donated nearly a billion dollars to Congressional candidates for this midterm cycle alone. Not only does every major business sector have a demonstrable financial interest in (and hedgeable exposure to) the Congressional balance of power, but that exposure is nicely asymmetric, making electoral outcomes especially well-suited to the risk reallocation function of futures markets.

3. Might these markets interfere with election integrity?

A common argument against offering electoral contracts on exchanges holds that such markets are somehow corrosive to election integrity. But that amounts to little more than a knee-jerk reaction to any novel intersection between money and politics.

Ironically, the wholly uncontroversial idea that money is a corrosive force in politics is one of the strongest arguments in favor of listing electoral outcomes on regulated exchanges. So universal and overwhelming is the exposure of virtually every commercial concern to electoral outcomes that countless commercial entities shovel as much money as legally permissible (at times, perhaps more) at the candidates and parties they feel pose less threat of enacting adverse policy changes.

What better way to reduce that pernicious imperative than to offer a more sanitized, transparent, duly regulated mechanism through which market participants can offset such unwanted exposure, with no attending influence over candidates and elected officials?

Two steps forward…another step forward?

Big leaps in accommodative financial regulation tend to come about once the public, then later the regulators, finally get over some initial revulsion. Life insurance, after all, was long decried as a morbid, obscene tool to gamble on your own (or someone else’s) mortality. And thanks to one chap who managed to corner the onion market briefly back in the 1950s, Congress decided no American may ever again enter into an onion futures contract, and we’re still waiting for that one to be remedied.

It can take decades, but once we turn to a dispassionate analysis of the merits and risks of a new product or structure, we tend to arrive at reasonable (if overdue) expansion of what flavors of financial innovation we as a society will allow.

Despite their byzantine rules, futures markets are simple things. They are risk transfer mechanisms—trading posts where we can standardize and swap exposures with one another.

For centuries, participants have been using these markets to manage their exposure to a dizzying range of external financial factors—everything from agricultural prices to interest rates to the price of bitcoin.

Political uncertainty is undeniably the largest category of external financial risk you’re helpless to manage. It’s well past time we allow futures market operators and participants to blaze a trail across this final frontier.

Flip Pidot, managing partner of Sharp Square Capital and CEO of American Civics Exchange, focuses on event-based futures. He formerly served as market curator at PredictIt and as a forensic accountant for Arthur Andersen. @flippidot

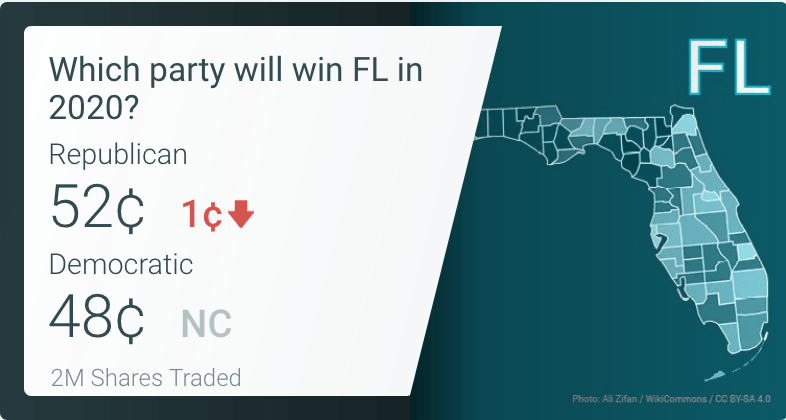

HOW PREDICTION MARKETS WORK

Prediction markets allow real money wagering to forecast the outcome of political events. Contracts trade between 1¢ and 99¢, and the price reflects the market’s consensus forecasted probability of an event occurring. When an outcome is determined, correct contracts pay out $1 and incorrect contracts settle worthless, at 0¢.