Ailing Commercial Real Estate Sector Could Compound Problems for Regional Banks

The current banking crisis is especially troublesome for the ailing commercial real estate industry because 80% of the loans from this sector are held by community and regional banks.

The 2023 banking crisis is frightening in its own right, but instability in the banking sector is especially worrisome because these institutions represent the backbone of the U.S. financial system.

That means trouble in the banks could spill over to other parts of the economy and create serious collateral damage. At present, one major concern is that the already vulnerable commercial real estate sector could be one of the next major casualties in the current crisis.

The commercial real estate sector in the U.S. is estimated at roughly $20 trillion, and is delineated by property that’s used for business purposes. The most common types of commercial real estate include office space, industrial space, retail space, hotels and multifamily rentals.

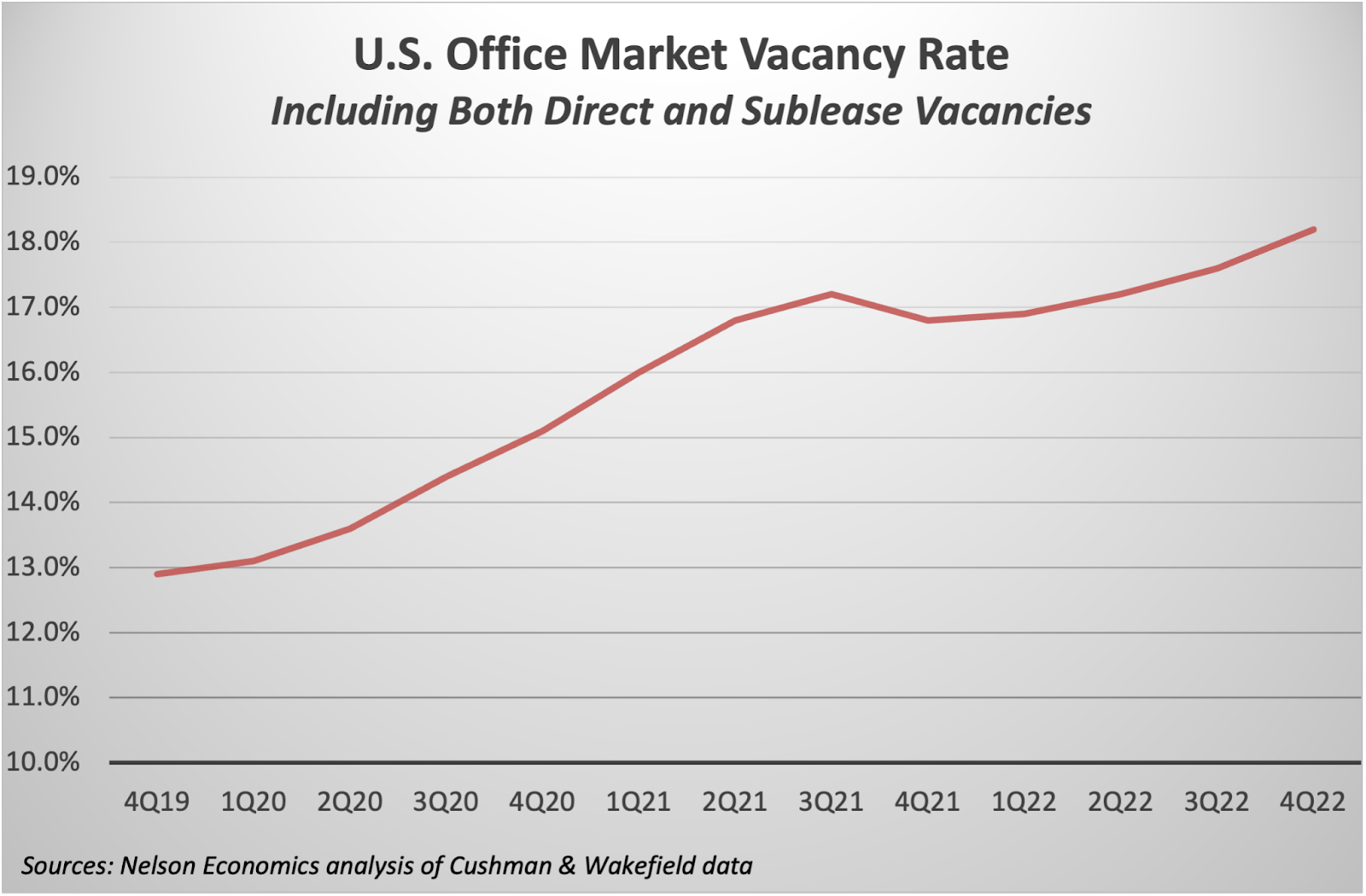

Unfortunately, those are some of the same sectors within the real estate industry that were hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. And even as the pandemic fades, the commercial real estate market still hasn’t fully recovered—especially office and retail-orientated properties.

That means the weakest parts of the commercial real estate sector are now facing a triple whammy—rising financing costs (via higher interest rates), higher vacancy rates, and lower valuations—as illustrated in the tweet below.

There is $1.5T in commercial real estate debt maturing in the next 3 years. The bulk of this debt was financed when base interest rates were near zero. This debt needs to be refinanced in an environment where rates are higher, values are lower, & in a market with less liquidity.

— Scott Rechler (@ScottRechler) March 22, 2023

What’s especially troublesome is that the majority of loans outstanding in the commercial real estate sector are held by mid-tier regional banks—the exact type that are under pressure in the current banking crisis.

A recent report from Goldman Sachs highlighted that more than 80% of all commercial real estate loans in the United States are currently held by banks with less than $250 billion in total assets. Moreover, it’s estimated that roughly $300 billion in commercial real estate loans are set to expire this year—the highest figure on record.

That means $300 billion in loans need to be refinanced during a period of instability for both borrowers (i.e. commercial real estate companies) and lenders (i.e. regional banks).

Like most businesses, commercial real estate companies benefited immensely when the Federal Reserve cut interest rates to near-zero during the heart of the COVID pandemic. However, that relatively rosy situation turned to thorns after the U.S. central bank was forced to substantially raise rates in order to fight record inflation.

Last March the secured overnight finance rate (SOFR)—a benchmark for many commercial mortgages—was close to zero. Today, however, that same rate is above 4.50%.

That’s an immense difference when it comes to financing a commercial mortgage. And even more so when one considers that rental income has declined as compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Vacancies and Defaults are Rising

In Manhattan, for example, total office availability was close to 19% in Q4 of 2022, which was the highest on record. That means office-focused commercial real estate companies are being forced to absorb higher financing costs, while at the same time dealing with reduced rental income and worrisome vacancy trends

Unless something changes in the foreseeable future, the combined weight of those burdens could translate to a fresh wave of defaults in the sector. And based on the aforementioned commercial mortgage statistics, the regional banks stand to lose the most under that unfortunate scenario.

For now, delinquencies in the commercial real estate sector aren’t out of control, and only ticked up marginally during the last quarter of 2022. However, there have been several high-profile defaults in Q1 2023.

For example, in mid-February, Brookfield (BN) defaulted on two major office properties in Los Angeles worth a combined $784 million. Brookfield is the largest owner of office space in the Los Angeles market, and those properties represented two of its “trophy” towers in downtown L.A.

Along those lines, Columbia Property Trust recently defaulted on $1.7 billion in loans that were tied to seven office properties across the United States. The combined value of that credit event represented the largest office-related default since the start of the pandemic.

As if all that wasn’t enough, the San Francisco Business Times recently reported that the second-largest office complex in San Francisco has been added to a loan servicer watchlist. The building is located at 555 California Street, and is co-owned by the Vornado Realty Trust (VN) and the Trump Organization.

That loan isn’t yet in default, but its addition to the loan servicer watchlist indicates that challenges have arisen that potentially threaten the borrowers’ ability to stay current on the loan.

One of the major concerns is that office tenants continue moving to smaller properties that are better suited for a hybrid work environment. And even if they don’t end up moving, tenants can use that leverage to negotiate better terms for their existing leases.

In either case, the net result is reduced revenue for office property owners. And as buildings become less profitable, they also tend to drop in value. That pushes up the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, which is a key metric used by lenders to evaluate the risk associated with a commercial real estate loan.

The LTV ratio is calculated by taking the total loan amount and dividing it by the total appraised value of the building(s). Lower LTV ratios are obviously preferred, and typically translate to better lending terms for the borrower.

Currently, there’s roughly $4.5 trillion outstanding in loans to the $20 trillion commercial real estate sector, which means the overall LTV ratio for the industry is roughly 22.5% ($4.5/$20 = 22.5%). A significant uptick in the overall industry LTV ratio could foreshadow a spike in defaults.

Trading the Commercial Real Estate Sector

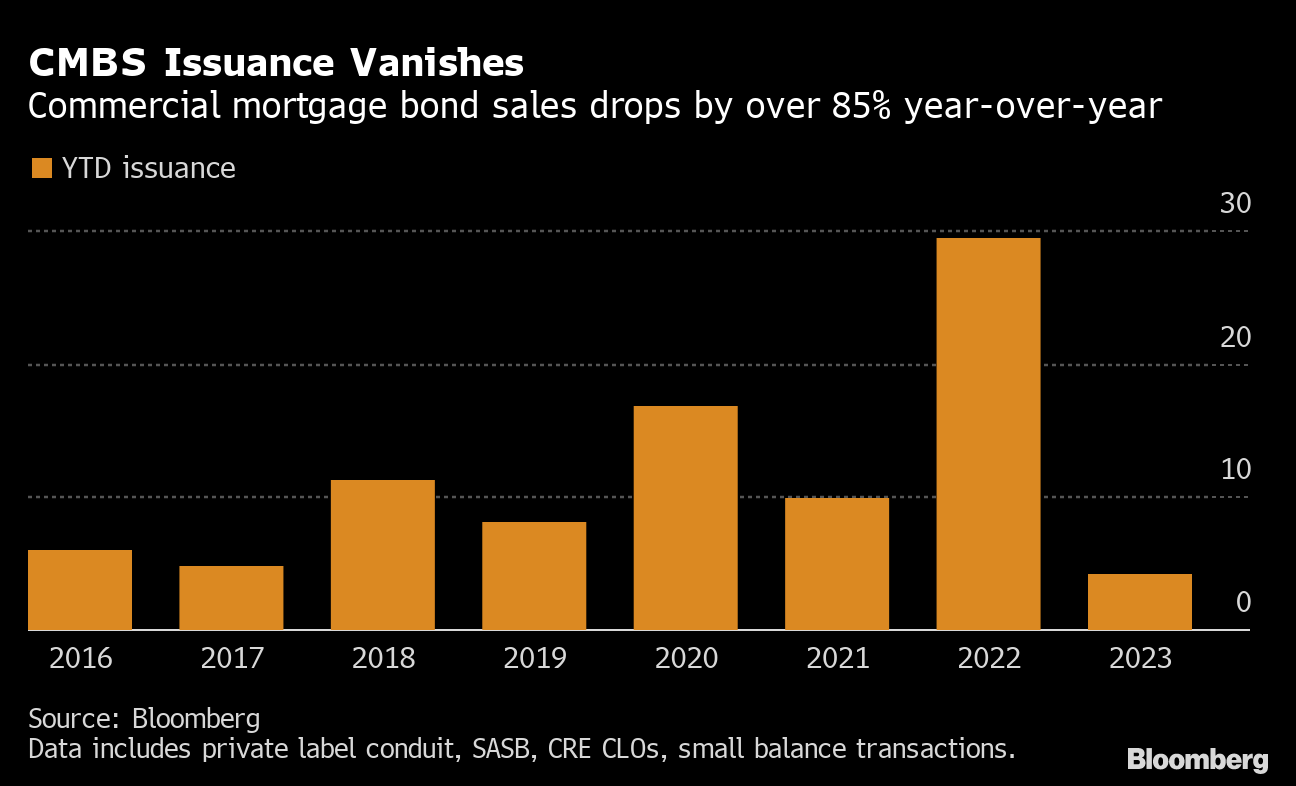

Sales of bonds linked to commercial mortgages are also suffering in 2023, which is another sign that the industry is ailing.

As illustrated below, just over $4 billion in commercial bonds had been issued by mid-February of this year, which was down from $29 billion at the same time last year.

Last year, large national banks in the U.S. apparently saw the writing on the wall and stepped back somewhat from the commercial mortgage market. According to Gerard Sansosti—a managing director at Jones Lang LaSalle (JLL)—smaller community and regional banks stepped in to pick up the slack.

Last Fall, Mr. Sansosti told the Urban Land Institute, “We have done a lot of business with local community and regional banks over the last three to six months.” Those are the exact institutions that are under pressure as a result of recent bank failures in the U.S.

Taken all together, that means commercial real estate companies and their lenders of choice are currently treading on thin ice, and may be especially vulnerable to further deterioration in the underlying economy.

For this reason, investors and traders may want to monitor this niche of the U.S. economy extremely closely in the coming months.

In the stock market, commercial real estate companies are often represented as real estate investment trusts (REIT), which are companies that own income-generating real estate. To qualify as a REIT, a company must derive at least 75% of gross income from rents, interest on mortgages that finance real property, or real estate sales

REITs can be diversified across the spectrum of commercial real estate, but most focus on one or two particular subsectors, whether it be apartment complexes, data centers, healthcare facilities, hotels, office buildings, retail centers, self-storage, timberland or warehouses.

To track and trade the commercial real estate sector—with particular emphasis on office properties—readers can add the following REITs to their watchlists.

- Alexandria Real Estate Equities (ARE)

- Boston Properties (BXP)

- Corporate Office Properties Trust (OFC)

- Cousins Properties (CUZ)

- Douglas Emmett (DEI)

- Equity Commonwealth (EQC)

- Highwoods Properties (HIW)

- JBG SMITH Properties (JBGS)

- Kilroy Realty Corp (KRC)

- Realty Income (O)

- SL Green Realty (SLG)

- Vornado Realty Trust (VNO)

To follow everything moving the markets, tune into tastylive, weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. CDT.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. He’s an experienced trader of equity derivatives and has managed volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. He’s not an employee of Luckbox, tastylive or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about this blog or other trading-related subjects, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.