MOO: Selloff in Commodities Offers Fresh Opportunities in Agribusiness Sector

The prices of many agricultural-focused commodities have dropped sharply in recent months, offering new opportunities to invest/trade the agribusiness niche of the financial markets

- The prices of several key agricultural commodities have weakened dramatically in recent months.

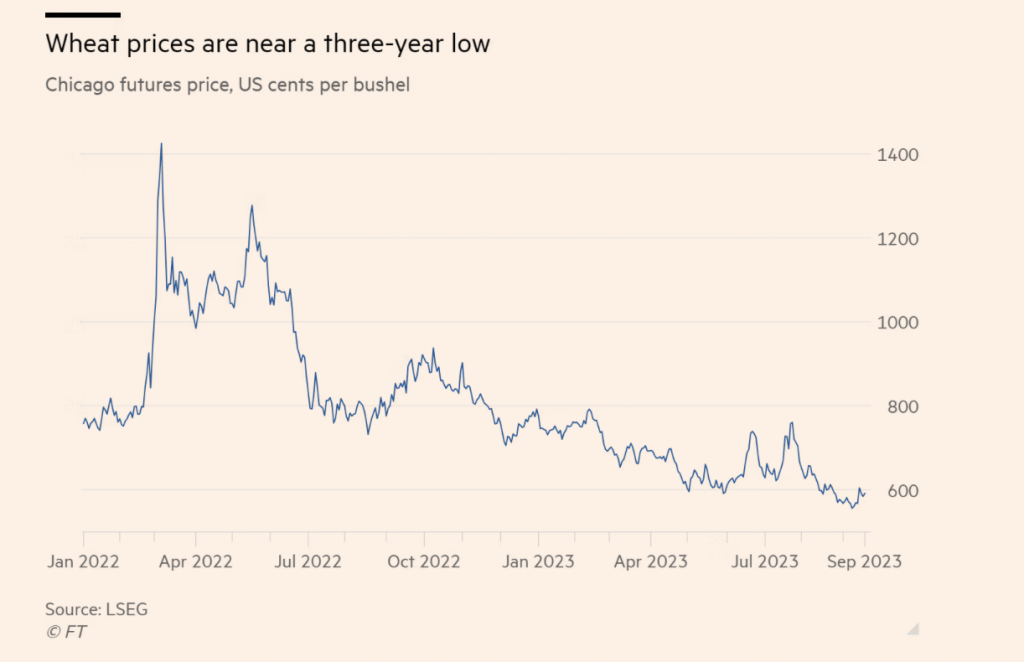

- Wheat prices, for example, have dipped toward a three-year low, dropping from above $14.00/bushel in 2022 all the way down to $5.40/bushel in autumn 2023.

- The VanEck Agribusiness ETF (MOO) may be poised to rebound in the coming months, especially if the global economy expands at a faster pace than expected in 2024.

When the Russian-Ukrainian War intensified in early 2022, the prices of many agricultural commodities spiked dramatically and remained elevated for much of that year.

However, during the course of the last 52 weeks, the prices of several key agricultural commodities—corn, soybeans and wheat—have steadily declined.

After peaking above $14/bushel in 2022, wheat prices dropped all the way down to $5.40/bushel in autumn of 2023. But wheat prices have recovered somewhat in recent weeks and are now trading closer to $6.50/bushel.

Notably, the recent rally in wheat has coincided with the broader rally in the major market indices. The S&P 500 is up roughly 11% since Oct. 27. It’s entirely possible that positive sentiment in the wheat market could spill over into the broader agricultural sector.

Much like ag-focused commodities, businesses levered to the agricultural sector have seen their shares trend lower in recent months. For example, the VanEck Agribusiness ETF (MOO) peaked at $108/share in spring of 2022 and has since dropped to about $74/share, representing a decline of more than 30%.

Not surprisingly, one of MOO’s largest holdings, Deere (DE), is also trading well off recent highs. Shares of Deere currently trade for about $363/share, which is 19% lower than the stock’s 52-week high of $450/share.

MOO may be poised to rebound in the coming months, especially if the global economy expands at a faster pace than expected in 2024.

Continuing impact from the war in Ukraine

Ukraine previously served as the “breadbasket” of Europe, producing vast amounts of agricultural commodities for the region.

For example, back in 2019, Ukraine exported roughly 21 million metric tons of wheat. But last year, that figure dropped all the way to 10.5 million metric tons, representing a decline of about 50% from 2019 levels.

Due to the ongoing war, it’s difficult to predict how much wheat Ukraine will export in 2024, but production will probably be on par with 2023, if not worse. That means global supplies of wheat will almost certainly remain constrained for the foreseeable future.

The recent downdraft in wheat prices appears to have triggered additional interest from buyers, suggesting that $5.50/bushel in the wheat markets represents somewhat of a floor in prices.

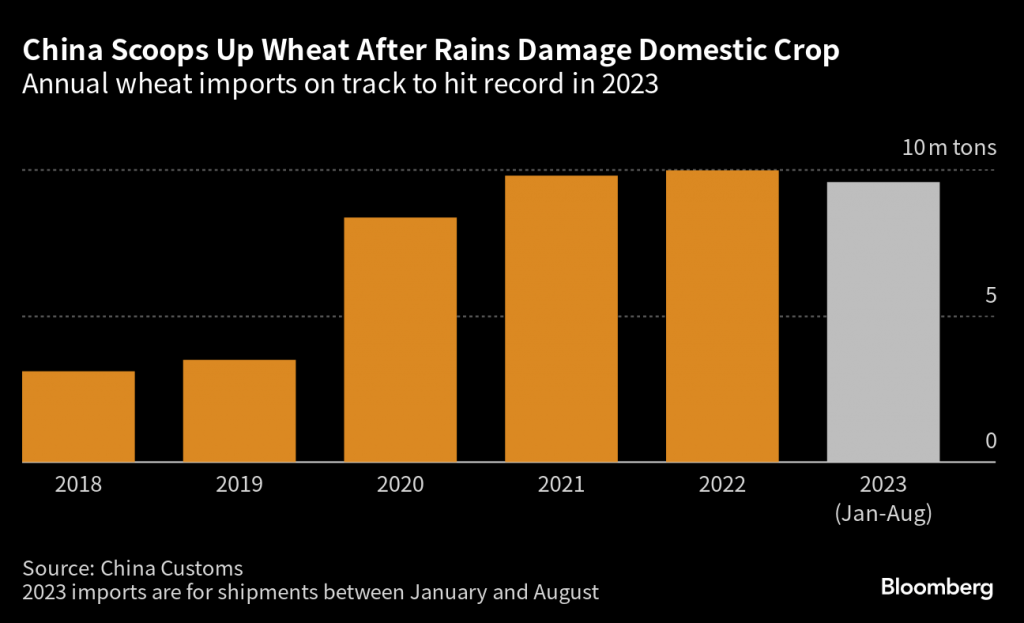

In the last several weeks, Chinese wheat buyers stepped into the market seeking to replenish their country’s supplies at favorable prices. China is one of the world’s largest annual importers of wheat, and could set a new record for total wheat imports in 2023.

In addition to wheat, corn and soybeans are two of the world’s other key ag-focused export commodities.

Today, soybeans trade at about $13/bushel, which is well off the 52-week high of closer to $16.50/bushel. However, the current price of soybeans is also ahead of 2020 levels, when soybeans traded for closer to $9/bushel.

Similar to soybeans and wheat, the price for corn has also dropped in 2023. Corn prices peaked last year over $8/bushel due to the war in Ukraine, but have since tailed back down to around $4.70/bushel.

Corn prices have been especially weak because many additional acres of corn were planted in 2023 as compared to 2022, as producers tried to take advantage of elevated prices. That contributed to a larger-than-expected harvest, which has weighed on prices.

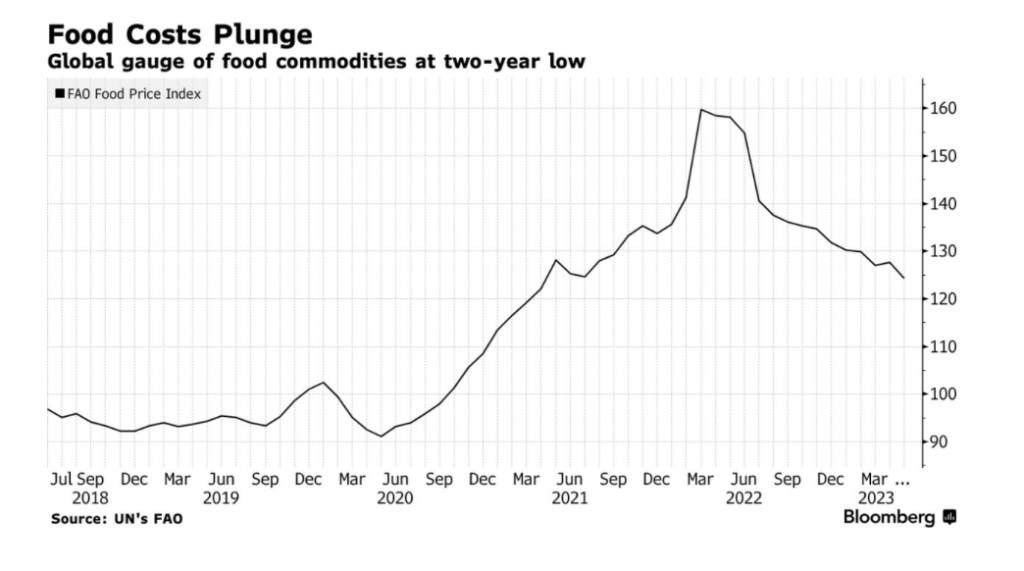

Looking at a broader gauge of world food prices, the well-known FAO Food Price Index (FFPI) has also retreated from all-time highs in 2023. The FFPI serves as a global indicator of food price trends and is used to monitor and analyze food price volatility and its potential impact on global food security.

In 2022, the FFPI peaked at roughly 160, but has since retreated to nearly 120. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the index traded around 95.

Why lower prices are a negative for the agribusiness sector

When Russia first expanded its war with Ukraine in early 2022, many agricultural commodities spiked in price due to concerns over potential shortages. At this point, however, the shock value of the war has worn off.

In recent months, the prices of many agricultural commodities have fallen back toward their long-term averages. Some of that price decline is due to improving fundamentals in the marketplace—supplies aren’t as constrained in 2023 as they were in 2022.

But on top of that, a portion of the recent retracement is linked to reduced fear in the marketplace. From that perspective, a portion of the recent price declines is attributable to reduced risk premiums in the marketplace.

Unfortunately, lower prices typically translate to lower revenues, and that’s undoubtedly been the case in the agribusiness sector. In its most recent earnings report, Deere revealed that its quarterly revenues had declined by 4% as compared to the same period 12 months ago.

Furthermore, Deere guided down its expected 2024 earnings, dropping its projected net income to about $8 billion, which was well below Wall Street’s expectation of $9 billion. Barrons noted that Deere’s earnings report reflected concerns that “farm incomes and prices for agricultural products have hit their peak.”

Unfortunately, that’s the harsh reality for commodities-focused businesses—revenue and earnings potential often ebbs and flows with market prices.

The oil industry provides a great example of this trend. When oil prices are depressed, the energy industry typically struggles financially. But when oil prices are soaring, oil-focused companies are usually awash with profits.

When agricultural prices are dropping, producers collect less from their harvests. And this year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture projects that total farm income will drop by about $42 billion as compared to last year. For companies like Deere, that situation contributes to a slowdown in sales.

Dollar-cost averaging and the appeal of MOO

At present, the big question is how much further prices will fall. And realistically, nobody knows for certain where (or when) prices will bottom out.

As a result, investors and traders active in this sector may want to start nibbling away at lower prices. This philosophy is typically referred to as dollar-cost averaging, which is a method of deploying smaller chunks of capital over a longer period of time, as opposed to deploying 100% of the total investment in one go.

Using dollar-cost averaging, an investor/trader can systematically build a position over time—an approach that’s especially attractive when prices are trending lower. In these cases, dollar-cost averaging allows an investor/trader to theoretically reduce the overall cost basis of his/her position.

For example, if one were to buy 100 shares of hypothetical stock XYZ at $100/share, and then another 100 shares of XYZ at $90/share, the investor/trader would own 200 shares with a cost basis of $95/share. Had the investor deployed all of the capital at once, his/her cost basis would be $100/share.

Looking at MOO, this well-diversified agricultural ETF is down roughly 30% since peaking in April of 2022. Today, MOO trades for about $74.00/share, with a 52-week low of $71.79/share.

Those prices are intriguing because leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, shares in MOO peaked at about $69/share. From a technical perspective, that indicates that MOO probably enjoys significant support at around$69-$70 per share, which may help explain why MOO recently bounced off from its 52-week low.

If MOO bounces from here, investors and traders that bought into a small position at these levels can simply ride the wave higher. But if MOO breaks through downside support, and falls below $70/share, that would present an attractive opportunity to lower one’s cost basis by purchasing additional shares.

At present, a total of 50 analysts cover MOO, of which 49 rate it a buy or hold. Only one analyst currently rates shares of MOO a sell. Moreover, the average price target for MOO is roughly $91/share, which is 23% higher than where the ETF trades today.

Interestingly, the range of those targets—including the lone sell rating—is $71/share to $124/share. With MOO currently trading for $74/share, that means the worst case scenario (according to professional equity analysts) represents a decline of only 4% from current levels.

Of course, market participants can also play a potential rebound in the agricultural sector via a long position in one of the aforementioned commodities. That could be through a futures position, or a commodities-focused ETF such as the Teucrium Corn ETF (CORN), the Teucrium Soybean Fund (SOYB), or the Teucrium Wheat Fund (WEAT).

Readers looking to invest in single stocks levered to the agricultural sector may also want to consider shares of FMC Corporation (FMC). As highlighted recently on Seeking Alpha, shares of FMC represent a compelling value proposition at this time.

For more background on dollar-cost averaging, readers can check out this installment of Market Measures on the tastylive financial network. To follow everything moving the markets, including the commodities markets, readers can tune into tastylive—weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. CDT.

Andrew Prochnow has more than 15 years of experience trading the global financial markets, including 10 years as a professional options trader. Andrew is a frequent contributor Luckbox Magazine.

For daily financial market news and commentary, visit the News & Insights page at tastylive or the YouTube channels tastylive (for options traders), and tastyliveTrending for stocks, futures, forex & macro.

Trade with a better broker, open a tastytrade account today. tastylive, Inc. and tastytrade, Inc. are separate but affiliated companies.