Making Rain

Prediction markets will pay you to get the weather forecast right—something made easier if you know what to look for

Babylonians attempted to predict the weather as early as 650 B.C. by looking at cloud patterns in the sky. Today, meteorologists use images and data transmitted by satellites tens of thousands of miles above the Earth’s surface. Forecasting has come a long way.

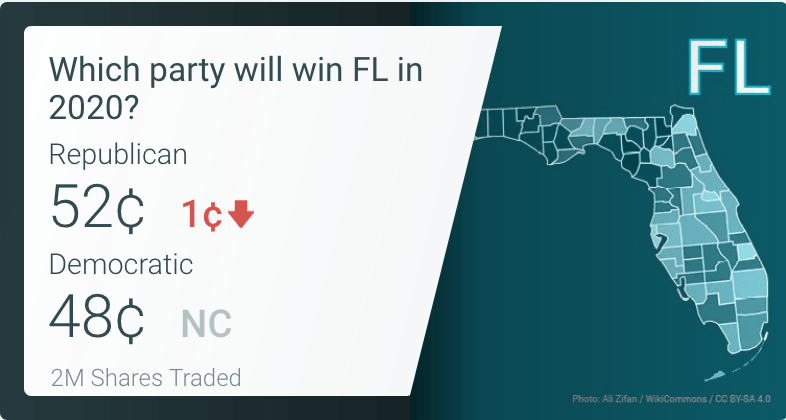

Event-based prediction markets represent yet another tool for weather forecasting, albeit a terrestrial one still in its infancy. But what makes prediction markets unique is that virtually anyone can participate in them, and a forecaster’s accuracy—or lack thereof—bears real financial consequences.

In short, it pays to be a better weather bettor.

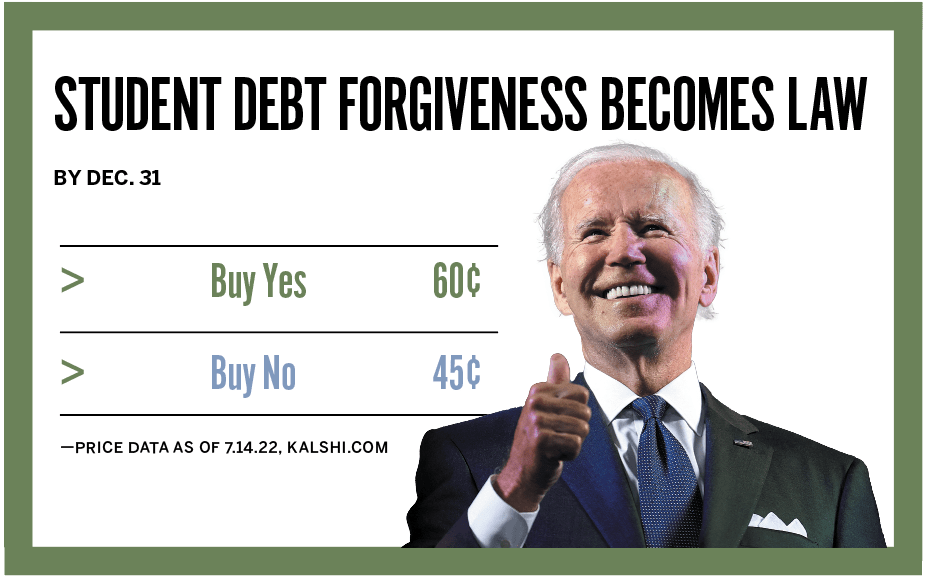

On the federally regulated events exchange Kalshi, daily recurring markets attempt to forecast high temperatures for New York City and Chicago. Other daily markets aim to forecast whether it will rain in New York City and Seattle.

Market structures vary. For instance, a “Seattle rain” market may simply forecast whether the city will record greater than zero inches of rain on a given day. Traders could buy “Yes” or “No” shares for a fraction of a dollar, with share prices roughly representing the market’s forecasted probability of a specific outcome.

When the market ultimately resolves, correct shares pay out for the full dollar, and incorrect shares become worthless.

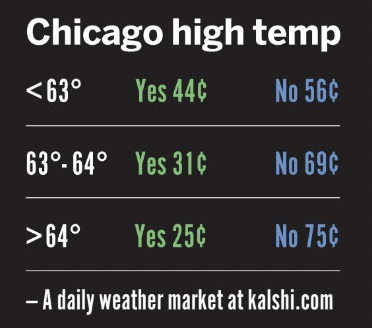

Alternatively, high temperature markets may be broken up into multiple contracts, each with their own “Yes” and “No” shares. A “Chicago high temp” market, for example, may have contracts for “less than 63 degrees,” “63 degrees to 64 degrees” and “greater than 64 degrees.”

To maximize profits, a trader convinced the temperature won’t break 63 degrees could buy “Yes” shares of the “less than 63 degrees” contract and “No” shares of all the others. Less confident traders could use the variety of contracts to hedge their forecasts.

With advanced weather data just keystrokes away, it may seem tempting to dive headfirst into Kalshi’s climate markets. But the following tips are essential for first-time weather traders hoping to avoid rookie mistakes.

1. Know what you’re forecasting

New York City and Chicago are big cities—big enough that the weather in one part may differ from the weather in another. That’s why it’s critically important to read each market’s rules summary and understand what determines its resolution before placing a trade.

Doing so will show that Chicago markets are determined by data recorded at Chicago Midway International Airport, and New York City markets are based on records for Central Park. It could rain torrentially in Lower Manhattan, but if the rain never hits Central Park, it won’t affect the market’s outcome.

Underlyings may change from day to day, too. A market forecasting if it will rain greater than zero inches in Seattle today may forecast whether it will rain greater than a half of an inch tomorrow. Always read the rules.

2. Refer to reliable resources

A market’s rules summary not only shows where to look for weather data but also what specific weather data to look at. All of Kalshi’s daily weather markets use the National Weather Service (NWS) as its source agency—more specifically, NWS daily climate reports.

Forecasters can explore the NWS’s daily climate reports by going to weather.gov/wrh/climate, but to access the data more easily, specific source agencies are hyperlinked under each market’s rules summary.

Parsing the daily climate reports shows maximum, minimum and average temperature readings, precipitation amounts and other data that could aid in more informed forecasting.

3. Be prepared to hedge your bet

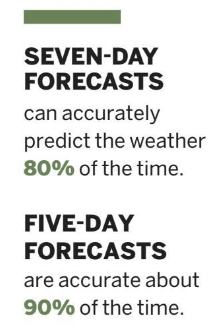

Anyone who’s been hit by a surprise rainstorm knows the NWS is far from perfect, and making day-of trades based solely on its forecasts will undoubtedly result in losses. However, the earlier traders enter a climate market, the less they’ll likely pay for the shares.

Generally speaking, Kalshi’s climate markets are posted over a day in advance of their closures. With over 24 hours of uncertainty baked into their prices, it’s usually pretty affordable to hedge in markets with multiple contracts.

Take the “Chicago high temp” example mentioned earlier. If “Yes” shares are hypothetically trading for 44 cents in the “less than 63 degrees” contract and 31 cents in the “63 degrees to 64 degrees” contract, buying an equal number of both shares effectively serves as a 75-cent “Yes” on the temperature staying under 64 degrees.

If the NWS forecast for the day is 62 degrees, that two-degree buffer can help save a forecaster’s portfolio from burning up if the weather gets hotter than predicted.