The Cost of Overconfidence

Hubris erects a barrier to good forecasting. Unchecked, it could prove expensive.

With SPACs all the rage, it’s important not to get too carried away by the rhetoric. Overconfidence can be expensive.

This is true in geopolitics, public health or the stock market. From the 1961 Bay of Pigs debacle to the slow response to the COVID-19 crisis, to millions of dollars lost speculating in the markets, history is filled with costly examples.

And yet, our culture continues to overvalue bold statements. Time and time again, the media turn to pundits who speak with conviction despite their spotty track records when it comes to offering real foresight.

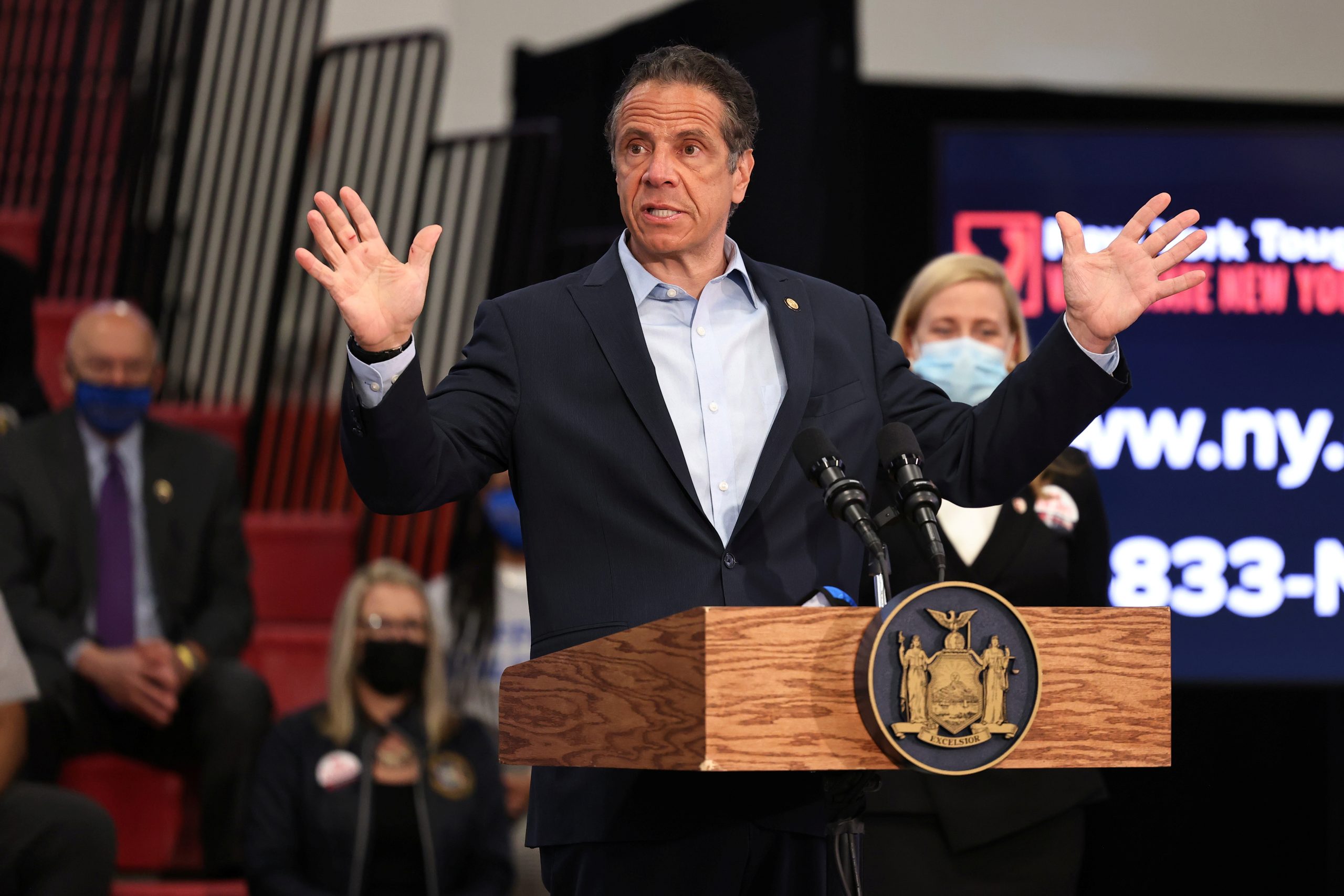

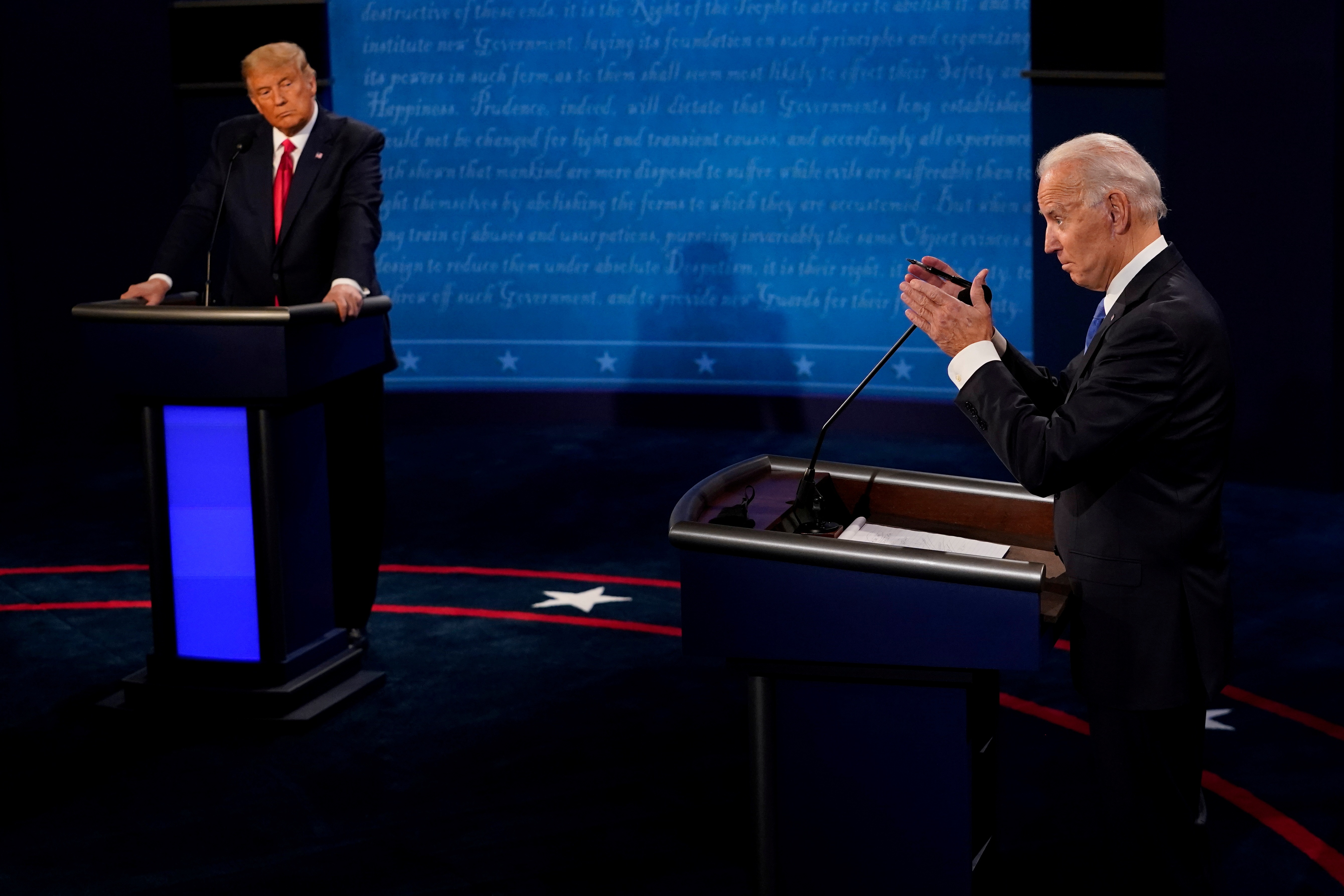

Think back to a year ago, when the airwaves were filled with experts and politicians confidently asserting that Covid-19 would swiftly pass. President Trump claimed in February 2020 that the coronavirus was under control and would disappear “like a miracle.” It took another month for the administration to acknowledge the severity of the unfolding pandemic.

Fox-like forecasting

“A confident yes or no is satisfying in a way that maybe never is, a fact that helps to explain why the media so often turn to hedgehogs who are sure they know what is coming no matter how bad their forecasting records may be,” writes Good Judgment’s co-founder Philip Tetlock in his book with Dan Gardner, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction.

Tetlock refers to a distinction between “foxes” and “hedgehogs,” a metaphor borrowed from ancient Greek poetry and popularized by the philosopher Isaiah Berlin: “The fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

Hedgehogs tend to be more confident—and more likely to get media attention—but, as researchers have found in multiple experiments, they also tend to be worse forecasters. Foxes, in contrast, tend to think in terms of “however” and “on the other hand.” They switch mental gears and talk about probabilities instead of certainties.

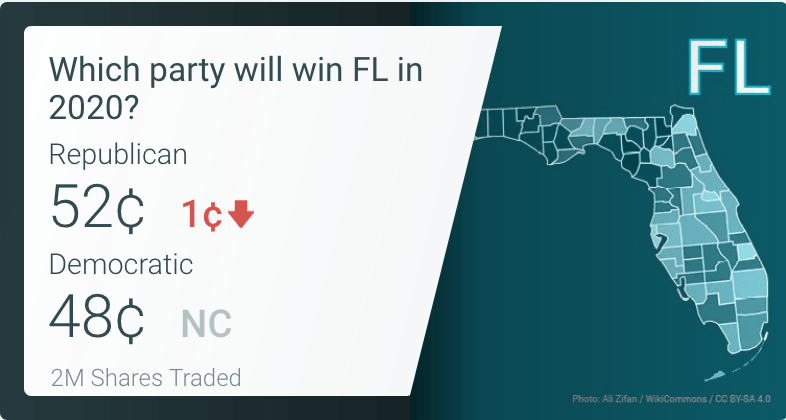

For instance, last year Good Judgment’s Superforecasters were estimating with a 67% probability that worldwide cases of Covid-19 would exceed 53 million within a year, and a 99% probability that deaths in the United States alone would be more than 200,000—a figure many found inordinate at the time.

The Superforecasters proved right in both cases. Their judgment was, and continues to be, well-calibrated. In other words, they know what they know and know what they don’t know, and they make their forecasts accordingly.

Banishing overconfidence

To avoid overconfidence, Superforecasters consider worst-case scenarios. Instead of relying on hunches and past success, they seek out evidence that those hunches may be wrong. They embrace new information and are not afraid to change their mind in light of new evidence.

Alas, pundits and most of the media have yet to join the foxes. “We live in a world that rewards those who speak with conviction—even when that is misplaced—and gives very little airtime to those who acknowledge doubt,” writes Financial Times columnist Jemima Kelly.

The sense of security that comes with confident judgments is comforting. But it is an illusion.

The cost of that illusion can be steep: from the inadequate early response to the pandemic to the investors trading to their detriment because they are overconfident about their ability to predict stock market returns.

Superforecasters know a way to avoid that cost: In a world that overvalues hedgehogs, pay more attention to your inner fox.

Warren Hatch, a former Wall Street investor, is CEO of Good Judgment Inc., a commercial enterprise that provides forecasts and forecasting training based on the expertise and research of the Good Judgment Project. @wfrhatch

Tune in to The Prediction Trade podcast from Luckbox for all-new ways to make money forecasting the financial markets, politics, crypto, sports and other events.